In this fourth part of the series on structured concurrency (Part-I, Part-II, Part-III, Swift-Followup), I will review Kotlin and Swift languages for writing concurrent applications and their support for structured concurrency:

Kotlin

Kotlin is a JVM language that was created by JetBrains with improved support of functional and object-oriented features such as extension functions, nested functions, data classes, lambda syntax, etc. Kotlin also uses optional types instead of null references similar to Rust and Swift to remove null-pointer errors. Kotlin provides native OS-threads similar to Java and coroutines with async/await syntax similar to Rust. Kotlin brings first-class support for structured concurrency with its support for concurrency scope, composition, error handling, timeout/cancellation and context for coroutines.

Structured Concurrency in Kotlin

Kotlin provides following primitives for concurrency support:

suspend functions

Kotlin adds suspend keyword to annotate a function that will be used by coroutine and it automatically adds continuation behavior when code is compiled so that instead of return value, it calls the continuation callback.

Launching coroutines

A coroutine can be launched using launch, async or runBlocking, which defines scope for structured concurrency. The lifetime of children coroutines is attached to this scope that can be used to cancel children coroutines. The async returns a Deferred (future) object that extends Job. You use await method on the Deferred instance to get the results.

Dispatcher

Kotlin defines CoroutineDispatcher to determine thread(s) for running the coroutine. Kotlin provides three types of dispatchers: Default – that are used for long-running asynchronous tasks; IO – that may use IO/network; and Main – that uses main thread (e.g. on Android UI).

Channels

Kotlin uses channels for communication between coroutines. It defines three types of channels: SendChannel, ReceiveChannel, and Channel. The channels can be rendezvous, buffered, unlimited or conflated where rendezvous channels and buffered channels behave like GO’s channels and suspend send or receive operation if other go-routine is not ready or buffer is full. The unlimited channel behave like queue and conflated channel overwrites previous value when new value is sent. The producer can close send channel to indicate end of work.

Using async/await in Kotlin

Following code shows how to use async/await to build the toy web crawler:

package concurrency

import concurrency.domain.Request

import concurrency.domain.Response

import concurrency.utils.CrawlerUtils

import kotlinx.coroutines.*

import org.slf4j.LoggerFactory

import java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicInteger

class CrawlerWithAsync(val maxDepth: Int, val timeout: Long) : Crawler {

private val logger = LoggerFactory.getLogger(CrawlerWithCoroutines::class.java)

val crawlerUtils = CrawlerUtils(maxDepth)

// public method for crawling a list of urls using async/await

override fun crawl(urls: List<String>): Response {

var res = Response()

// Boundary for concurrency and it will not return until all

// child URLs are crawled up to MAX_DEPTH limit.

runBlocking {

res.childURLs = crawl(urls, 0).childURLs

}

return res

}

suspend private fun crawl(urls: List<String>, depth: Int): Response {

var res = Response()

if (depth >= maxDepth) {

return res.failed("Max depth reached")

}

var size = AtomicInteger()

withTimeout(timeout) {

val jobs = mutableListOf<Deferred<Int>>()

for (u in urls) {

jobs.add(async {

val childURLs = crawlerUtils.handleCrawl(Request(u, depth))

// shared

size.addAndGet(crawl(childURLs, depth + 1).childURLs + 1)

})

}

for (j in jobs) {

j.await()

}

}

return res.completed(size.get())

}

}In above example, CrawlerWithAsync class defines timeout parameter for crawler. The crawl function takes list of URLs to crawl and defines high-level scope of concurrency using runBlocking. The private crawl method is defined as suspend so that it can be used as continuation. It uses async with timeout to start background tasks and uses await to collect results. This method recursively calls handleCrawl to crawl child URLs.

Following unit tests show how to test above crawl method:

package concurrency

import org.junit.Test

import org.slf4j.LoggerFactory

import kotlin.test.assertEquals

class CrawlerAsynTest {

private val logger = LoggerFactory.getLogger(CrawlerWithCoroutinesTest::class.java)

val urls = listOf("a.com", "b.com", "c.com", "d.com", "e.com", "f.com",

"g.com", "h.com", "i.com", "j.com", "k.com", "l.com", "n.com")

@Test

fun testCrawl() {

val crawler = CrawlerWithAsync(4, 1000L)

val started = System.currentTimeMillis()

val res = crawler.crawl(urls);

val duration = System.currentTimeMillis() - started

logger.info("CrawlerAsync - crawled %d urls in %d milliseconds".format(res.childURLs, duration))

assertEquals(19032, res.childURLs)

}

@Test(expected = Exception::class)

fun testCrawlWithTimeout() {

val crawler = CrawlerWithAsync(1000, 100L)

crawler.crawl(urls);

}

}You can download the full source code from https://github.com/bhatti/concurency-katas/tree/main/kot_pool.

Following are major benefits of using this approach to implement crawler and its support of structured concurrency:

- The main crawl method defines high level scope of concurrency and it waits for the completion of child tasks.

- Kotlin supports cancellation and timeout APIs and the crawl method will fail with timeout error if crawling exceeds the time limit.

- The crawl method captures error from async response and returns so that client code can perform error handling.

- The async syntax in Kotlin allows easy composition of asynchronous code.

- Kotlin allows customized dispatcher for more control on the asynchronous behavior.

Following are shortcomings using this approach for structured concurrency and general design:

- As Kotlin doesn’t enforce immutability by default, you will need synchronization to protect shared state.

- Async/Await support is still new in Kotlin and lacks stability and proper documentation.

- Above design creates a new coroutine for crawling each URL and it can strain expensive network and IO resources so it’s not practical for real-world implementation.

Using coroutines in Kotlin

Following code uses coroutine syntax to implement the web crawler:

package concurrency

import concurrency.domain.Request

import concurrency.domain.Response

import concurrency.utils.CrawlerUtils

import kotlinx.coroutines.coroutineScope

import kotlinx.coroutines.runBlocking

import kotlinx.coroutines.withTimeout

import org.slf4j.LoggerFactory

import java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicInteger

class CrawlerWithCoroutines(val maxDepth: Int, val timeout: Long) : Crawler {

private val logger = LoggerFactory.getLogger(CrawlerWithCoroutines::class.java)

val crawlerUtils = CrawlerUtils(maxDepth)

// public method for crawling a list of urls using coroutines

override fun crawl(urls: List<String>): Response {

var res = Response()

// Boundary for concurrency and it will not return until all

// child URLs are crawled up to MAX_DEPTH limit.

runBlocking {

res.childURLs = crawl(urls, 0).childURLs

}

return res

}

suspend private fun crawl(urls: List<String>, depth: Int): Response {

var res = Response()

if (depth >= maxDepth) {

return res.failed("Max depth reached")

}

var size = AtomicInteger()

withTimeout(timeout) {

for (u in urls) {

coroutineScope {

val childURLs = crawlerUtils.handleCrawl(Request(u, depth))

// shared

size.addAndGet(crawl(childURLs, depth + 1).childURLs + 1)

}

}

}

return res.completed(size.get())

}

}Above example is similar to async/await but uses coroutine syntax and its behavior is similar to async/await implementation.

Following example shows how async coroutines can be cancelled:

package concurrency

import concurrency.domain.Request

import concurrency.domain.Response

import concurrency.utils.CrawlerUtils

import kotlinx.coroutines.Deferred

import kotlinx.coroutines.async

import kotlinx.coroutines.runBlocking

import kotlinx.coroutines.withTimeout

import org.slf4j.LoggerFactory

import java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicInteger

class CrawlerCancelable(val maxDepth: Int, val timeout: Long) : Crawler {

private val logger = LoggerFactory.getLogger(CrawlerWithCoroutines::class.java)

val crawlerUtils = CrawlerUtils(maxDepth)

// public method for crawling a list of urls to show cancel operation

// internal method will call cancel instead of await so this method will

// fail.

override fun crawl(urls: List<String>): Response {

var res = Response()

// Boundary for concurrency and it will not return until all

// child URLs are crawled up to MAX_DEPTH limit.

runBlocking {

res.childURLs = crawl(urls, 0).childURLs

}

return res

}

////////////////// Internal methods

suspend private fun crawl(urls: List<String>, depth: Int): Response {

var res = Response()

if (depth >= maxDepth) {

return res.failed("Max depth reached")

}

var size = AtomicInteger()

withTimeout(timeout) {

val jobs = mutableListOf<Deferred<Int>>()

for (u in urls) {

jobs.add(async {

val childURLs = crawlerUtils.handleCrawl(Request(u, depth))

// shared

size.addAndGet(crawl(childURLs, depth + 1).childURLs + 1)

})

}

for (j in jobs) {

j.cancel()

}

}

return res.completed(size.get())

}

}You can download above examples from https://github.com/bhatti/concurency-katas/tree/main/kot_pool.

Swift

Swift was developed by Apple to replace Objective-C and offer modern features such as closures, optionals instead of null-pointers (similar to Rust and Kotlin), optionals chaining, guards, value types, generics, protocols, algebraic data types, etc. It uses same runtime system as Objective-C and uses automatic-reference-counting (ARC) for memory management, grand-central-dispatch for concurrency and provides integration with Objective-C code and libraries.

Structured Concurrency in Swift

I discussed concurrency support in Objective-C in my old blog [1685] such as NSThread, NSOperationQueue, Grand Central Dispatch (GCD), etc and since then GCD has improved launching asynchronous tasks using background queues with timeout/cancellation support. However, much of the Objective-C and Swift code still suffers from callbacks and promises hell discussed in Part-I. Chris Lattner and Joe Groff wrote a proposal to add async/await and actor-model to Swift and provide first-class support for structured concurrency. As this work is still in progress, I wasn’t able to test it but here are major features of this proposal:

Coroutines

Swift will adapt coroutines as building blocks of concurrency and asynchronous code. It will add syntactic sugar for completion handlers using async or yield keywords.

Async/Await

Swift will provide async/await syntactic sugar on top of coroutines to mark asynchronous behavior. The async code will use continuations similar to Kotlin so that it suspends itself and schedules execution by controlling context. It will use Futures (similar to Deferred in Kotlin) to await for the results (or errors). This syntax will work with normal error handling in Swift so that errors from asynchronous code are automatically propagated to the calling function.

Actor model

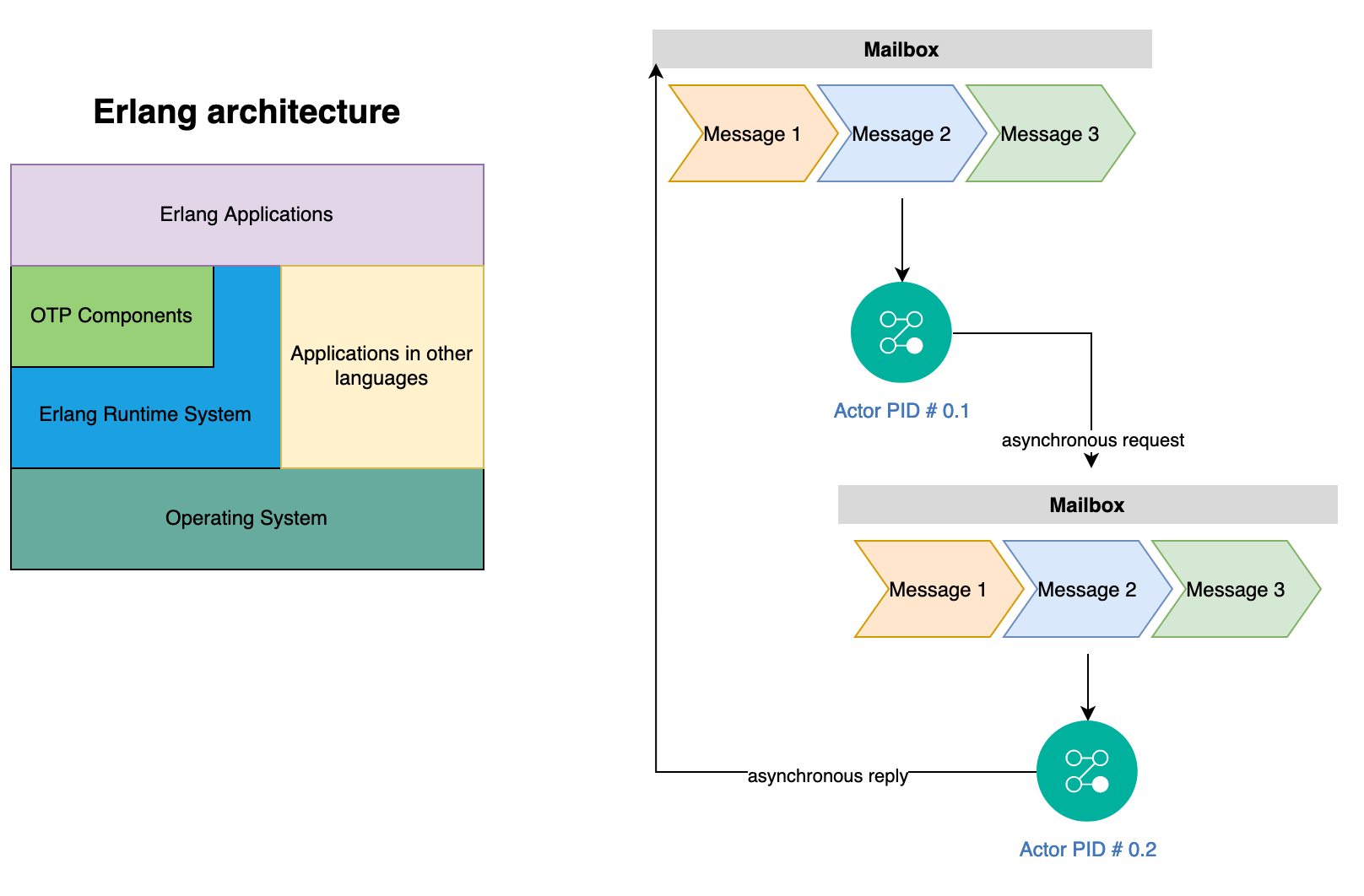

Swift will adopt actor-model with value based messages (copy-on-write) to manage concurrent objects that can receive messages asynchronously and the actor can keep internal state and eliminate race conditions.

Kotlin and Swift are very similar in design and both have first-class support of structured concurrency such as concurrency scope, composition, error handling, cancellation/timeout, value types, etc. Both Kotlin and Swift use continuation for async behavior so that async keyword suspends the execution and passes control to the execution context so that it can be executed asynchronously and control is passed back at the end of execution.

Structured Concurrency Comparison

Following table summarizes support of structured concurrency discussed in this blog series:

| Feature | Typescript (NodeJS) | Erlang | Elixir | GO | Rust | Kotlin | Swift |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structured scope | Built-in | manually | manually | manually | Built-in | Built-in | Built-in |

| Asynchronous Composition | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Error Handling | Natively using Exceptions | Manually storing errors in Response | Manually storing errors in Response | Manually storing errors in Response | Manually using Result ADT | Natively using Exceptions | Natively using Exceptions |

| Cancellation | Cooperative Cancellation | Built-in Termination or Cooperative Cancellation | Built-in Termination or Cooperative Cancellation | Built-in Cancellation or Cooperative Cancellation | Built-in Cancellation or Cooperative Cancellation | Built-in Cancellation or Cooperative Cancellation | Built-in Cancellation or Cooperative Cancellation |

| Timeout | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Customized Execution Context | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Race Conditions | No due to NodeJS architecture | No due to Actor model | No due to Actor model | Possible due to shared state | No due to strong ownership | Possible due to shared state | Possible due to shared state |

| Value Types | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

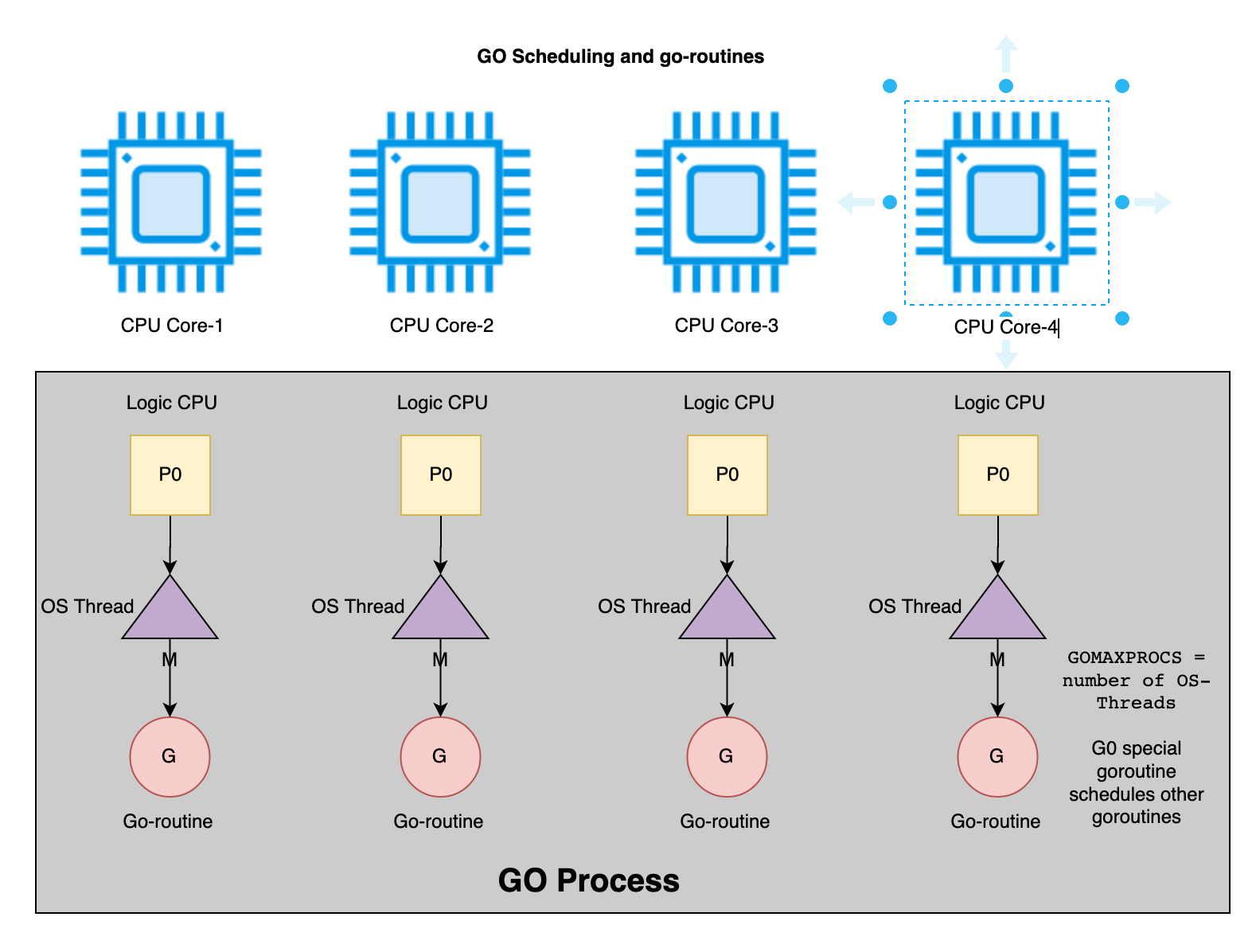

| Concurrency paradigms | Event loop | Actor model | Actor model | Go-routine, CSP channels | OS-Thread, coroutine | OS-Thread, coroutine, CSP channels | OS-Thread, GCD queues, coroutine, Actor model |

| Type Checking | Static | Dynamic | Dynamic | Static but lacks generics | Strongly static types with generics | Strongly static types with generics | Strongly static types with generics |

| Suspends Async code using Continuations | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zero-cost based abstraction ( async) | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Memory Management | GC | GC (process-scoped) | GC (process-scoped) | GC | (Automated) Reference counting, Boxing | GC | Automated reference counting |

Performance Comparison

Following table summarizes runtime of various implementation of web crawler when crawling 19K URLs that resulted in about 76K messages to asynchronous methods/coroutines/actors discussed in this blog series:

| Language | Design | Runtime (secs) |

| Typescript | Async/Await | 0.638 |

| Erlang | Spawning Process | 4.636 |

| Erlang | PMAP | 4.698 |

| Elixir | Spawning OTP Children | 43.5 |

| Elixir | Task async/await | 187 |

| Elixir | Worker-pool with queue | 97 |

| GO | Go-routine/channels | 1.2 |

| Rust | Async/Await | 4.3 |

| Kotlin | Async/Await | 0.736 |

| Kotlin | Coroutine | 0.712 |

| Swift | Async/Await | 63 |

| Swift | Actors/Async/Await | 65 |

Summary

Overall, Typescript/NodeJS provides a simpler model for concurrency but lacks proper timeout/cancellation support and it’s not suitable for highly concurrent applications that require blocking APIs. The actor based concurrency model in Erlang/Elixir supports high-level of concurrency, error handling, cancellation and isolates process state to prevent race conditions but it lacks composing asynchronous behavior natively. Though, you can compose Erlang processes with parent-child hierarchy and easily start or stop these processes. GO supports concurrency via go-routines and channels with built-in cancellation and timeout APIs but GO statements are considered harmful by structured concurrency and it doesn’t protect against race conditions due to mutable state. Erlang and GO are the only languages that were designed from ground-up with support for actors and coroutines and their schedulers have strong support for asynchronous IO and non-blocking APIs. Erlang also offers process-scoped garbage collection to clean up related data easily as opposed to global GC in other languages. The async/await support in Rust is still immature and lacks proper support of cancellation but strong ownership properties of Rust eliminate race conditions and allows safe concurrency. Rust, Kotlin and Swift uses continuation for async/await that allows composition for multiple async/await chained together. For example, instead of using await (await download()).parse() in Javascript/Typescript/C#, you can use await download().parse(). The async/await changes are still new in Kotlin and lack stability whereas Swift has not yet released these changes as part of official release. As Kotlin, Rust, and Swift built coroutines or async/await on top of existing runtime and virtual machine, their green-thread schedulers are not as optimal as schedulers in Erlang or GO and may exhibit limitations on concurrency and scalability.

Finally, structured concurrency helps your code structure with improved data/control flow, concurrency scope, error handling, cancellation/timeout and composition but it won’t solve data races if multiple threads/coroutines access mutable shared data concurrently so you will need to rely on synchronization mechanisms to protect the critical section.

Note: You can download all examples in this series from https://github.com/bhatti/concurency-katas.