Over the years, I have seen countless production issues due to improper transaction management. A typical example: an API requires changes to multiple database tables, and each update is wrapped in different methods without proper transaction boundaries. This works fine when everything goes smoothly, but due to database constraints or other issues, a secondary database update might fail. In too many cases, the code doesn’t handle proper rollback and just throws an error—leaving the database in an inconsistent state.

In other cases, I’ve debugged production bugs due to improper coordination between database updates and event queues, where we desperately needed atomic behavior. I used J2EE in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which provided support for two-phase commit (2PC) to coordinate multiple updates across resources. However, 2PC wasn’t a scalable solution. I then experimented with aspect-oriented programming like AspectJ to handle cross-cutting concerns like transaction management, but it resulted in more complex code that was difficult to debug and maintain.

Later, I moved to Java Spring, which provided annotations for transaction management. This was both efficient and elegant—the @Transactional annotation made transaction boundaries explicit without cluttering business logic. When I worked at a travel booking company where we had to coordinate flight reservations, hotel bookings, car rentals, and insurance through various vendor APIs, I built a transaction framework based on the command pattern and chain of responsibility. This worked well for issuing compensating transactions when a remote API call failed midway through our public API workflow.

However, when I moved to Go and Rust, I found a lack of these basic transaction management primitives. I often see bugs in Go and Rust codebases that could have been caught earlier—many implementations assume the happy path and don’t properly handle partial failures or rollback scenarios.

In this blog, I’ll share learnings from my experience across different languages and platforms. I’ll cover best practices for establishing proper transaction boundaries, from single-database ACID transactions to distributed SAGA patterns, with working examples in Java/Spring, Go, and Rust. The goal isn’t just to prevent data corruption—it’s to build systems you can reason about, debug, and trust.

The Happy Path Fallacy

Most developers write code assuming everything will work perfectly. Here’s a typical “happy path” implementation:

// This looks innocent but is fundamentally broken

public class OrderService {

public void processOrder(Order order) {

orderRepository.save(order); // What if this succeeds...

paymentService.chargeCard(order); // ...but this fails?

inventoryService.allocate(order); // Now we have inconsistent state

emailService.sendConfirmation(order); // And this might never happen

}

}

The problem isn’t just that operations can fail—it’s that partial failures leave your system in an undefined state. Without proper transaction boundaries, you’re essentially playing Russian roulette with your data integrity. In my experience analyzing production systems, I’ve found that most data corruption doesn’t come from dramatic failures or outages. It comes from these subtle, partial failures that happen during normal operation. A network timeout here, a service restart there, and suddenly your carefully designed system is quietly hemorrhaging data consistency.

Transaction Fundamentals

Before we dive into robust transaction management in our applications, we need to understand what databases actually provide and how they achieve consistency guarantees. Most developers treat transactions as a black box—call BEGIN, do some work, call COMMIT, and hope for the best. But understanding the underlying mechanisms is crucial for making informed decisions about isolation levels, recognizing performance implications, and debugging concurrency issues when they inevitably arise in production. Let’s examine the foundational concepts that every developer working with transactions should understand.

The ACID Foundation

Before diving into implementation patterns, let’s establish why ACID properties matter:

- Atomicity: Either all operations in a transaction succeed, or none do

- Consistency: The database remains in a valid state before and after the transaction

- Isolation: Concurrent transactions don’t interfere with each other

- Durability: Once committed, changes survive system failures

These aren’t academic concepts—they’re the guardrails that prevent your system from sliding into chaos. Let’s see how different languages and frameworks help us maintain these guarantees.

Isolation Levels: The Hidden Performance vs Consistency Tradeoff

Most developers don’t realize that their database isn’t using the strictest isolation level by default. In fact, most production databases (MySQL, PostgreSQL, Oracle, SQL Server) default to READ COMMITTED, not SERIALIZABLE. This creates subtle race conditions that can lead to double spending and other financial disasters.

// The double spending problem with default isolation

@Service

public class VulnerableAccountService {

// This uses READ COMMITTED by default - DANGEROUS for financial operations!

@Transactional

public void withdrawFunds(String accountId, BigDecimal amount) {

Account account = accountRepository.findById(accountId);

// RACE CONDITION: Another transaction can modify balance here!

if (account.getBalance().compareTo(amount) >= 0) {

account.setBalance(account.getBalance().subtract(amount));

accountRepository.save(account);

} else {

throw new InsufficientFundsException();

}

}

}

// What happens with concurrent requests:

// Thread 1: Read balance = $100, check passes

// Thread 2: Read balance = $100, check passes

// Thread 1: Withdraw $100, balance = $0

// Thread 2: Withdraw $100, balance = -$100 (DOUBLE SPENDING!)

Database Default Isolation Levels

| Database | Default Isolation | Financial Safety |

|---|---|---|

| PostgreSQL | READ COMMITTED | ? Vulnerable |

| MySQL | REPEATABLE READ | ?? Better but not perfect |

| Oracle | READ COMMITTED | ? Vulnerable |

| SQL Server | READ COMMITTED | ? Vulnerable |

| H2/HSQLDB | READ COMMITTED | ? Vulnerable |

The Right Way: Database Constraints + Proper Isolation

// Method 1: Database constraints (fastest)

@Entity

@Table(name = "accounts")

public class Account {

@Id

private String accountId;

@Column(nullable = false)

@Check(constraints = "balance >= 0") // Database prevents negative balance

private BigDecimal balance;

@Version

private Long version;

}

@Service

public class SafeAccountService {

// Let database constraint handle the race condition

@Transactional

public void withdrawFundsWithConstraint(String accountId, BigDecimal amount) {

try {

Account account = accountRepository.findById(accountId);

account.setBalance(account.getBalance().subtract(amount));

accountRepository.save(account); // Database throws exception if balance < 0

} catch (DataIntegrityViolationException e) {

throw new InsufficientFundsException("Withdrawal would result in negative balance");

}

}

// Method 2: SERIALIZABLE isolation (most secure)

@Transactional(isolation = Isolation.SERIALIZABLE)

public void withdrawFundsSerializable(String accountId, BigDecimal amount) {

Account account = accountRepository.findById(accountId);

if (account.getBalance().compareTo(amount) >= 0) {

account.setBalance(account.getBalance().subtract(amount));

accountRepository.save(account);

} else {

throw new InsufficientFundsException();

}

// SERIALIZABLE guarantees no other transaction can interfere

}

// Method 3: Optimistic locking (good performance)

@Transactional

@Retryable(value = {OptimisticLockingFailureException.class}, maxAttempts = 3)

public void withdrawFundsOptimistic(String accountId, BigDecimal amount) {

Account account = accountRepository.findById(accountId);

if (account.getBalance().compareTo(amount) >= 0) {

account.setBalance(account.getBalance().subtract(amount));

accountRepository.save(account); // Version check prevents race conditions

} else {

throw new InsufficientFundsException();

}

}

}

MVCC

Most developers don’t realize that modern databases achieve isolation levels through Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC), not traditional locking. Understanding MVCC explains why certain isolation behaviors seem counterintuitive. Instead of locking rows for reads, databases maintain multiple versions of each row with timestamps. When you start a transaction, you get a consistent snapshot of the database as it existed at that moment.

// What actually happens under MVCC

@Transactional(isolation = Isolation.REPEATABLE_READ)

public void demonstrateMVCC() {

// T1: Transaction starts, gets snapshot at time=100

Account account = accountRepository.findById("123"); // Reads version at time=100

// T2: Another transaction modifies the account (creates version at time=101)

// T1: Reads same account again

Account sameAccount = accountRepository.findById("123"); // Still reads version at time=100!

assert account.getBalance().equals(sameAccount.getBalance()); // MVCC guarantees this

}

MVCC vs Traditional Locking

-- Traditional locking approach (not MVCC) BEGIN TRANSACTION; SELECT * FROM accounts WHERE id = '123' FOR SHARE; -- Acquires shared lock -- Other transactions blocked from writing until this transaction ends -- MVCC approach (PostgreSQL, MySQL InnoDB) BEGIN TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL REPEATABLE READ; SELECT * FROM accounts WHERE id = '123'; -- No locks, reads from snapshot -- Other transactions can write freely, creating new versions

MVCC delivers better performance and reduces deadlock contention compared to traditional locking, but it comes with cleanup overhead requirements (PostgreSQL VACUUM, MySQL purge operations). I have encountered numerous production issues where real-time queries or ETL jobs would suddenly degrade in performance due to aggressive background VACUUM operations on older PostgreSQL versions, though recent versions have significantly improved this behavior. MVCC can also lead to stale reads in long-running transactions, as they maintain their snapshot view even as the underlying data changes.

// MVCC write conflict example

@Transactional

@Retryable(value = {OptimisticLockingFailureException.class})

public void updateAccountMVCC(String accountId, BigDecimal newBalance) {

Account account = accountRepository.findById(accountId);

// If another transaction modified this account between our read

// and write, MVCC will detect the conflict and retry

account.setBalance(newBalance);

accountRepository.save(account); // May throw OptimisticLockingFailureException

}

This is why PostgreSQL defaults to READ COMMITTED and why long-running analytical queries should use dedicated read replicas—MVCC snapshots can become expensive to maintain over time.

Java and Spring: The Gold Standard

Spring’s @Transactional annotation is probably the most elegant solution I’ve encountered for transaction management. It uses aspect-oriented programming to wrap methods in transaction boundaries, making the complexity invisible to business logic.

Basic Transaction Management

@Service

@Transactional

public class OrderService {

@Autowired

private OrderRepository orderRepository;

@Autowired

private PaymentService paymentService;

@Autowired

private InventoryService inventoryService;

// All operations within this method are atomic

public Order processOrder(CreateOrderRequest request) {

Order order = new Order(request);

order = orderRepository.save(order);

// If any of these fail, everything rolls back

Payment payment = paymentService.processPayment(

order.getCustomerId(),

order.getTotalAmount()

);

inventoryService.reserveItems(order.getItems());

order.setPaymentId(payment.getId());

order.setStatus(OrderStatus.CONFIRMED);

return orderRepository.save(order);

}

}

Different Transaction Types

Spring provides fine-grained control over transaction behavior:

@Service

public class OrderService {

// Read-only transactions can be optimized by the database

@Transactional(readOnly = true)

public List<Order> getOrderHistory(String customerId) {

return orderRepository.findByCustomerId(customerId);

}

// Long-running operations need higher timeout

@Transactional(timeout = 300) // 5 minutes

public void processBulkOrders(List<CreateOrderRequest> requests) {

for (CreateOrderRequest request : requests) {

processOrder(request);

}

}

// Critical operations need strict isolation

@Transactional(isolation = Isolation.SERIALIZABLE)

public void transferInventory(String fromLocation, String toLocation,

String itemId, int quantity) {

Item fromItem = inventoryRepository.findByLocationAndItem(fromLocation, itemId);

Item toItem = inventoryRepository.findByLocationAndItem(toLocation, itemId);

if (fromItem.getQuantity() < quantity) {

throw new InsufficientInventoryException();

}

fromItem.setQuantity(fromItem.getQuantity() - quantity);

toItem.setQuantity(toItem.getQuantity() + quantity);

inventoryRepository.save(fromItem);

inventoryRepository.save(toItem);

}

// Some operations should create new transactions

@Transactional(propagation = Propagation.REQUIRES_NEW)

public void logAuditEvent(String event, String details) {

AuditLog log = new AuditLog(event, details, Instant.now());

auditRepository.save(log);

// This commits immediately, independent of calling transaction

}

// Handle specific rollback conditions

@Transactional(rollbackFor = {BusinessException.class, ValidationException.class})

public void processComplexOrder(ComplexOrderRequest request) {

// Business logic that might throw business exceptions

validateOrderRules(request);

Order order = createOrder(request);

processPayment(order);

}

}

Nested Transactions and Propagation

Understanding nested transactions is critical for building robust systems. In some cases, you want a child transaction to succeed regardless of whether the parent transaction succeeds or not—these are often called “autonomous transactions” or “independent transactions.” The solution was to use REQUIRES_NEW propagation for audit operations, creating independent transactions that commit immediately regardless of what happens to the parent transaction. Similarly, for notification services, you typically want notifications to be sent even if the business operation partially fails—users should know that something went wrong.

@Service

public class OrderProcessingService {

@Autowired

private OrderService orderService;

@Autowired

private NotificationService notificationService;

@Transactional

public void processOrderWithNotification(CreateOrderRequest request) {

// This participates in the existing transaction

Order order = orderService.processOrder(request);

// This creates a new transaction that commits independently

notificationService.sendOrderConfirmation(order);

// If something fails here, the order transaction can still commit

// but the notification might not be sent

}

}

@Service

public class NotificationService {

// Creates a new transaction - notifications are sent even if

// the main order processing fails later

@Transactional(propagation = Propagation.REQUIRES_NEW)

public void sendOrderConfirmation(Order order) {

NotificationRecord record = new NotificationRecord(

order.getCustomerId(),

"Order confirmed: " + order.getId(),

NotificationType.ORDER_CONFIRMATION

);

notificationRepository.save(record);

// Send actual notification asynchronously

emailService.sendAsync(order.getCustomerEmail(),

"Order Confirmation",

generateOrderEmail(order));

}

}

Go with GORM: Explicit Transaction Management

Go doesn’t have the luxury of annotations, so transaction management becomes more explicit. This actually has benefits—the transaction boundaries are clearly visible in the code.

Basic GORM Transactions

package services

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"gorm.io/gorm"

)

type OrderService struct {

db *gorm.DB

}

type Order struct {

ID uint `gorm:"primarykey"`

CustomerID string

TotalAmount int64

Status string

PaymentID string

Items []OrderItem `gorm:"foreignKey:OrderID"`

}

type OrderItem struct {

ID uint `gorm:"primarykey"`

OrderID uint

SKU string

Quantity int

Price int64

}

// Basic transaction with explicit rollback handling

func (s *OrderService) ProcessOrder(ctx context.Context, request CreateOrderRequest) (*Order, error) {

tx := s.db.Begin()

defer func() {

if r := recover(); r != nil {

tx.Rollback()

panic(r)

}

}()

order := &Order{

CustomerID: request.CustomerID,

TotalAmount: request.TotalAmount,

Status: "PENDING",

}

// Save the order

if err := tx.Create(order).Error; err != nil {

tx.Rollback()

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to create order: %w", err)

}

// Process payment

paymentID, err := s.processPayment(ctx, tx, order)

if err != nil {

tx.Rollback()

return nil, fmt.Errorf("payment failed: %w", err)

}

// Reserve inventory

if err := s.reserveInventory(ctx, tx, request.Items); err != nil {

tx.Rollback()

return nil, fmt.Errorf("inventory reservation failed: %w", err)

}

// Update order with payment info

order.PaymentID = paymentID

order.Status = "CONFIRMED"

if err := tx.Save(order).Error; err != nil {

tx.Rollback()

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to update order: %w", err)

}

if err := tx.Commit().Error; err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to commit transaction: %w", err)

}

return order, nil

}

Functional Transaction Wrapper

To reduce boilerplate, we can create a transaction wrapper:

// TransactionFunc represents a function that runs within a transaction

type TransactionFunc func(tx *gorm.DB) error

// WithTransaction wraps a function in a database transaction

func (s *OrderService) WithTransaction(fn TransactionFunc) error {

tx := s.db.Begin()

defer func() {

if r := recover(); r != nil {

tx.Rollback()

panic(r)

}

}()

if err := fn(tx); err != nil {

tx.Rollback()

return err

}

return tx.Commit().Error

}

// Now our business logic becomes cleaner

func (s *OrderService) ProcessOrderClean(ctx context.Context, request CreateOrderRequest) (*Order, error) {

var order *Order

err := s.WithTransaction(func(tx *gorm.DB) error {

order = &Order{

CustomerID: request.CustomerID,

TotalAmount: request.TotalAmount,

Status: "PENDING",

}

if err := tx.Create(order).Error; err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to create order: %w", err)

}

paymentID, err := s.processPaymentInTx(ctx, tx, order)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("payment failed: %w", err)

}

if err := s.reserveInventoryInTx(ctx, tx, request.Items); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("inventory reservation failed: %w", err)

}

order.PaymentID = paymentID

order.Status = "CONFIRMED"

return tx.Save(order).Error

})

return order, err

}

Context-Based Transaction Management

For more sophisticated transaction management, we can use context to pass transactions:

type contextKey string

const txKey contextKey = "transaction"

// WithTransactionContext creates a new context with a transaction

func WithTransactionContext(ctx context.Context, tx *gorm.DB) context.Context {

return context.WithValue(ctx, txKey, tx)

}

// TxFromContext retrieves a transaction from context

func TxFromContext(ctx context.Context) (*gorm.DB, bool) {

tx, ok := ctx.Value(txKey).(*gorm.DB)

return tx, ok

}

// GetDB returns either the transaction from context or the main DB

func (s *OrderService) GetDB(ctx context.Context) *gorm.DB {

if tx, ok := TxFromContext(ctx); ok {

return tx

}

return s.db

}

// Now services can automatically use transactions when available

func (s *PaymentService) ProcessPayment(ctx context.Context, customerID string, amount int64) (string, error) {

db := s.GetDB(ctx) // Uses transaction if available

payment := &Payment{

CustomerID: customerID,

Amount: amount,

Status: "PROCESSING",

}

if err := db.Create(payment).Error; err != nil {

return "", err

}

// Simulate payment processing

if amount > 100000 { // Reject large amounts for demo

payment.Status = "FAILED"

db.Save(payment)

return "", fmt.Errorf("payment amount too large")

}

payment.Status = "COMPLETED"

payment.TransactionID = generatePaymentID()

if err := db.Save(payment).Error; err != nil {

return "", err

}

return payment.TransactionID, nil

}

// Usage with context-based transactions

func (s *OrderService) ProcessOrderWithContext(ctx context.Context, request CreateOrderRequest) (*Order, error) {

var order *Order

return order, s.WithTransaction(func(tx *gorm.DB) error {

// Create context with transaction

txCtx := WithTransactionContext(ctx, tx)

order = &Order{

CustomerID: request.CustomerID,

TotalAmount: request.TotalAmount,

Status: "PENDING",

}

if err := tx.Create(order).Error; err != nil {

return err

}

// These services will automatically use the transaction

paymentID, err := s.paymentService.ProcessPayment(txCtx, order.CustomerID, order.TotalAmount)

if err != nil {

return err

}

if err := s.inventoryService.ReserveItems(txCtx, request.Items); err != nil {

return err

}

order.PaymentID = paymentID

order.Status = "CONFIRMED"

return tx.Save(order).Error

})

}

Read-Only and Isolation Control

// Read-only operations can be optimized

func (s *OrderService) GetOrderHistory(ctx context.Context, customerID string) ([]Order, error) {

var orders []Order

// Use read-only transaction for consistency

err := s.db.Transaction(func(tx *gorm.DB) error {

return tx.Raw("SELECT * FROM orders WHERE customer_id = ? ORDER BY created_at DESC",

customerID).Scan(&orders).Error

}, &sql.TxOptions{ReadOnly: true})

return orders, err

}

// Operations requiring specific isolation levels

func (s *InventoryService) TransferStock(ctx context.Context, fromSKU, toSKU string, quantity int) error {

return s.db.Transaction(func(tx *gorm.DB) error {

var fromItem, toItem InventoryItem

// Lock rows to prevent concurrent modifications

if err := tx.Set("gorm:query_option", "FOR UPDATE").

Where("sku = ?", fromSKU).First(&fromItem).Error; err != nil {

return err

}

if err := tx.Set("gorm:query_option", "FOR UPDATE").

Where("sku = ?", toSKU).First(&toItem).Error; err != nil {

return err

}

if fromItem.Quantity < quantity {

return fmt.Errorf("insufficient inventory")

}

fromItem.Quantity -= quantity

toItem.Quantity += quantity

if err := tx.Save(&fromItem).Error; err != nil {

return err

}

return tx.Save(&toItem).Error

}, &sql.TxOptions{Isolation: sql.LevelSerializable})

}

Rust: Custom Transaction Annotations with Macros

Rust doesn’t have runtime annotations like Java, but we can create compile-time macros that provide similar functionality. This approach gives us zero-runtime overhead while maintaining clean syntax.

Building a Transaction Macro System

First, let’s create the macro infrastructure:

// src/transaction/mod.rs

use diesel::prelude::*;

use diesel::result::Error as DieselError;

use std::fmt;

#[derive(Debug)]

pub enum TransactionError {

Database(DieselError),

Business(String),

Validation(String),

}

impl fmt::Display for TransactionError {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

match self {

TransactionError::Database(e) => write!(f, "Database error: {}", e),

TransactionError::Business(e) => write!(f, "Business error: {}", e),

TransactionError::Validation(e) => write!(f, "Validation error: {}", e),

}

}

}

impl std::error::Error for TransactionError {}

pub type TransactionResult<T> = Result<T, TransactionError>;

// Macro for creating transactional functions

#[macro_export]

macro_rules! transactional {

(

fn $name:ident($($param:ident: $param_type:ty),*) -> $return_type:ty {

$($body:tt)*

}

) => {

fn $name(conn: &mut PgConnection, $($param: $param_type),*) -> TransactionResult<$return_type> {

conn.transaction::<$return_type, TransactionError, _>(|conn| {

$($body)*

})

}

};

}

// Macro for read-only transactions

#[macro_export]

macro_rules! read_only {

(

fn $name:ident($($param:ident: $param_type:ty),*) -> $return_type:ty {

$($body:tt)*

}

) => {

fn $name(conn: &mut PgConnection, $($param: $param_type),*) -> TransactionResult<$return_type> {

// In a real implementation, we'd set READ ONLY mode

conn.transaction::<$return_type, TransactionError, _>(|conn| {

$($body)*

})

}

};

}

Using the Transaction Macros

// src/services/order_service.rs

use diesel::prelude::*;

use crate::transaction::*;

use crate::models::*;

use crate::schema::orders::dsl::*;

pub struct OrderService;

impl OrderService {

// Transactional order processing with automatic rollback

transactional! {

fn process_order(request: CreateOrderRequest) -> Order {

// Create the order

let new_order = NewOrder {

customer_id: &request.customer_id,

total_amount: request.total_amount,

status: "PENDING",

};

let order: Order = diesel::insert_into(orders)

.values(&new_order)

.get_result(conn)

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

// Process payment

let payment_id = Self::process_payment_internal(conn, &order)

.map_err(|e| TransactionError::Business(format!("Payment failed: {}", e)))?;

// Reserve inventory

Self::reserve_inventory_internal(conn, &request.items)

.map_err(|e| TransactionError::Business(format!("Inventory reservation failed: {}", e)))?;

// Update order with payment info

let updated_order = diesel::update(orders.filter(id.eq(order.id)))

.set((

payment_id.eq(&payment_id),

status.eq("CONFIRMED"),

))

.get_result(conn)

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

Ok(updated_order)

}

}

// Read-only transaction for queries

read_only! {

fn get_order_history(customer_id: String) -> Vec<Order> {

let order_list = orders

.filter(customer_id.eq(&customer_id))

.order(created_at.desc())

.load::<Order>(conn)

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

Ok(order_list)

}

}

// Helper functions that work within existing transactions

fn process_payment_internal(conn: &mut PgConnection, order: &Order) -> Result<String, String> {

use crate::schema::payments::dsl::*;

let new_payment = NewPayment {

customer_id: &order.customer_id,

order_id: order.id,

amount: order.total_amount,

status: "PROCESSING",

};

let payment: Payment = diesel::insert_into(payments)

.values(&new_payment)

.get_result(conn)

.map_err(|e| format!("Payment creation failed: {}", e))?;

// Simulate payment processing logic

if order.total_amount > 100000 {

diesel::update(payments.filter(id.eq(payment.id)))

.set(status.eq("FAILED"))

.execute(conn)

.map_err(|e| format!("Payment update failed: {}", e))?;

return Err("Payment amount too large".to_string());

}

let transaction_id = format!("txn_{}", uuid::Uuid::new_v4());

diesel::update(payments.filter(id.eq(payment.id)))

.set((

status.eq("COMPLETED"),

transaction_id.eq(&transaction_id),

))

.execute(conn)

.map_err(|e| format!("Payment finalization failed: {}", e))?;

Ok(transaction_id)

}

fn reserve_inventory_internal(conn: &mut PgConnection, items: &[OrderItemRequest]) -> Result<(), String> {

use crate::schema::inventory::dsl::*;

for item in items {

// Lock the inventory row for update

let mut inventory_item: InventoryItem = inventory

.filter(sku.eq(&item.sku))

.for_update()

.first(conn)

.map_err(|e| format!("Inventory lookup failed: {}", e))?;

if inventory_item.quantity < item.quantity {

return Err(format!("Insufficient inventory for SKU: {}", item.sku));

}

inventory_item.quantity -= item.quantity;

diesel::update(inventory.filter(sku.eq(&item.sku)))

.set(quantity.eq(inventory_item.quantity))

.execute(conn)

.map_err(|e| format!("Inventory update failed: {}", e))?;

}

Ok(())

}

}

Advanced Transaction Features in Rust

// More sophisticated transaction management with isolation levels

#[macro_export]

macro_rules! serializable_transaction {

(

fn $name:ident($($param:ident: $param_type:ty),*) -> $return_type:ty {

$($body:tt)*

}

) => {

fn $name(conn: &mut PgConnection, $($param: $param_type),*) -> TransactionResult<$return_type> {

// Set serializable isolation level

conn.batch_execute("SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL SERIALIZABLE")

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

conn.transaction::<$return_type, TransactionError, _>(|conn| {

$($body)*

})

}

};

}

// Usage for operations requiring strict consistency

impl InventoryService {

serializable_transaction! {

fn transfer_stock(from_sku: String, to_sku: String, quantity: i32) -> (InventoryItem, InventoryItem) {

use crate::schema::inventory::dsl::*;

// Lock both items in consistent order to prevent deadlocks

let (first_sku, second_sku) = if from_sku < to_sku {

(&from_sku, &to_sku)

} else {

(&to_sku, &from_sku)

};

let mut from_item: InventoryItem = inventory

.filter(sku.eq(first_sku))

.for_update()

.first(conn)

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

let mut to_item: InventoryItem = inventory

.filter(sku.eq(second_sku))

.for_update()

.first(conn)

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

// Ensure we have the right items

if from_item.sku != from_sku {

std::mem::swap(&mut from_item, &mut to_item);

}

if from_item.quantity < quantity {

return Err(TransactionError::Business(

"Insufficient inventory for transfer".to_string()

));

}

from_item.quantity -= quantity;

to_item.quantity += quantity;

let updated_from = diesel::update(inventory.filter(sku.eq(&from_sku)))

.set(quantity.eq(from_item.quantity))

.get_result(conn)

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

let updated_to = diesel::update(inventory.filter(sku.eq(&to_sku)))

.set(quantity.eq(to_item.quantity))

.get_result(conn)

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

Ok((updated_from, updated_to))

}

}

}

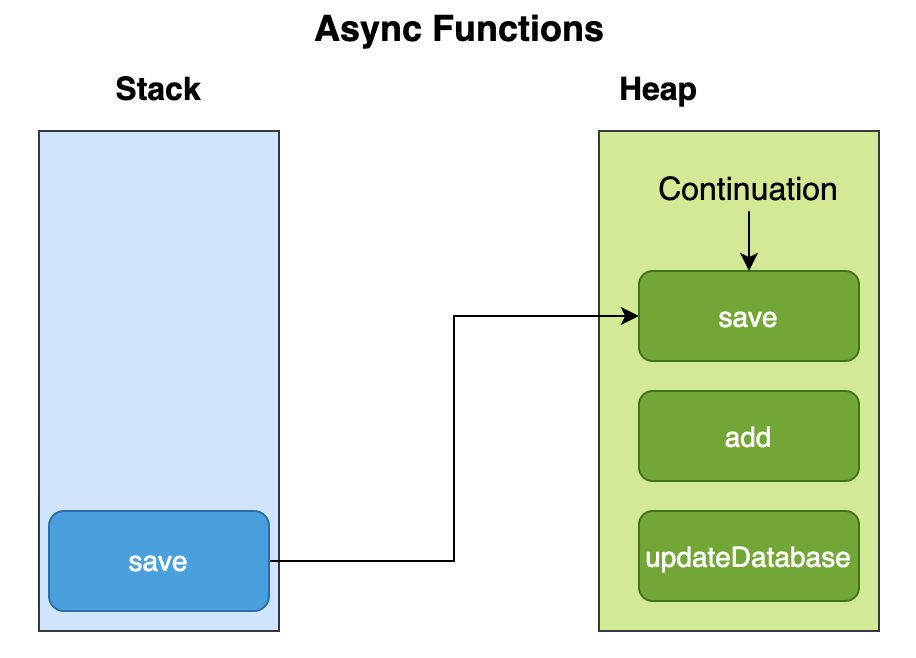

Async Transaction Support

For modern Rust applications using async/await:

// src/transaction/async_transaction.rs

use diesel_async::{AsyncPgConnection, AsyncConnection};

use diesel_async::pooled_connection::bb8::Pool;

#[macro_export]

macro_rules! async_transactional {

(

async fn $name:ident($($param:ident: $param_type:ty),*) -> $return_type:ty {

$($body:tt)*

}

) => {

async fn $name(pool: &Pool<AsyncPgConnection>, $($param: $param_type),*) -> TransactionResult<$return_type> {

let mut conn = pool.get().await

.map_err(|e| TransactionError::Database(e.into()))?;

conn.transaction::<$return_type, TransactionError, _>(|conn| {

Box::pin(async move {

$($body)*

})

}).await

}

};

}

// Usage with async operations

impl OrderService {

async_transactional! {

async fn process_order_async(request: CreateOrderRequest) -> Order {

// All the same logic as before, but with async/await support

let new_order = NewOrder {

customer_id: &request.customer_id,

total_amount: request.total_amount,

status: "PENDING",

};

let order: Order = diesel::insert_into(orders)

.values(&new_order)

.get_result(conn)

.await

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

// Process payment asynchronously

let payment_id = Self::process_payment_async(conn, &order).await

.map_err(|e| TransactionError::Business(format!("Payment failed: {}", e)))?;

// Continue with order processing...

Ok(order)

}

}

}

Multi-Database Transactions: Two-Phase Commit

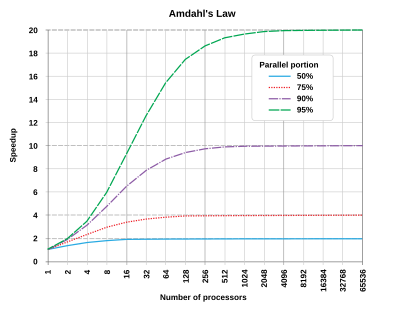

I used J2EE and XA transactions extensively in the late 1990s and early 2000s when these standards were being defined by Sun Microsystems with major contributions from IBM, Oracle, and BEA Systems. While these technologies provided strong consistency guarantees, they added enormous complexity to applications and resulted in significant performance issues. The fundamental problem with 2PC is that it’s a blocking protocol—if the transaction coordinator fails during the commit phase, all participating databases remain locked until the coordinator recovers. I’ve seen production systems grind to a halt for hours because of coordinator failures. There are also edge cases that 2PC simply cannot handle, such as network partitions between the coordinator and participants, which led to the development of three-phase commit (3PC). In most cases, you should avoid distributed transactions entirely and use patterns like SAGA, event sourcing, or careful service boundaries instead.

Java XA Transactions

@Configuration

@EnableTransactionManagement

public class XATransactionConfig {

@Bean

@Primary

public DataSource orderDataSource() {

MysqlXADataSource xaDataSource = new MysqlXADataSource();

xaDataSource.setURL("jdbc:mysql://localhost:3306/orders");

xaDataSource.setUser("orders_user");

xaDataSource.setPassword("orders_pass");

return xaDataSource;

}

@Bean

public DataSource inventoryDataSource() {

MysqlXADataSource xaDataSource = new MysqlXADataSource();

xaDataSource.setURL("jdbc:mysql://localhost:3306/inventory");

xaDataSource.setUser("inventory_user");

xaDataSource.setPassword("inventory_pass");

return xaDataSource;

}

@Bean

public JtaTransactionManager jtaTransactionManager() {

JtaTransactionManager jtaTransactionManager = new JtaTransactionManager();

jtaTransactionManager.setTransactionManager(atomikosTransactionManager());

jtaTransactionManager.setUserTransaction(atomikosUserTransaction());

return jtaTransactionManager;

}

@Bean(initMethod = "init", destroyMethod = "close")

public UserTransactionManager atomikosTransactionManager() {

UserTransactionManager transactionManager = new UserTransactionManager();

transactionManager.setForceShutdown(false);

return transactionManager;

}

@Bean

public UserTransactionImp atomikosUserTransaction() throws SystemException {

UserTransactionImp userTransactionImp = new UserTransactionImp();

userTransactionImp.setTransactionTimeout(300);

return userTransactionImp;

}

}

@Service

public class DistributedOrderService {

@Autowired

@Qualifier("orderDataSource")

private DataSource orderDataSource;

@Autowired

@Qualifier("inventoryDataSource")

private DataSource inventoryDataSource;

// XA transaction spans both databases

@Transactional

public void processDistributedOrder(CreateOrderRequest request) {

// Operations on orders database

try (Connection orderConn = orderDataSource.getConnection()) {

PreparedStatement orderStmt = orderConn.prepareStatement(

"INSERT INTO orders (customer_id, total_amount, status) VALUES (?, ?, ?)"

);

orderStmt.setString(1, request.getCustomerId());

orderStmt.setBigDecimal(2, request.getTotalAmount());

orderStmt.setString(3, "PENDING");

orderStmt.executeUpdate();

}

// Operations on inventory database

try (Connection inventoryConn = inventoryDataSource.getConnection()) {

for (OrderItem item : request.getItems()) {

PreparedStatement inventoryStmt = inventoryConn.prepareStatement(

"UPDATE inventory SET quantity = quantity - ? WHERE sku = ? AND quantity >= ?"

);

inventoryStmt.setInt(1, item.getQuantity());

inventoryStmt.setString(2, item.getSku());

inventoryStmt.setInt(3, item.getQuantity());

int updatedRows = inventoryStmt.executeUpdate();

if (updatedRows == 0) {

throw new InsufficientInventoryException("Not enough inventory for " + item.getSku());

}

}

}

// If we get here, both database operations succeeded

// The XA transaction manager will coordinate the commit across both databases

}

}

Go Distributed Transactions

Go doesn’t have built-in distributed transaction support, so we need to implement 2PC manually:

package distributed

import (

"context"

"database/sql"

"fmt"

"log"

"time"

"github.com/google/uuid"

)

type TransactionManager struct {

resources []XAResource

}

type XAResource interface {

Prepare(ctx context.Context, txID string) error

Commit(ctx context.Context, txID string) error

Rollback(ctx context.Context, txID string) error

}

type DatabaseResource struct {

db *sql.DB

name string

}

func (r *DatabaseResource) Prepare(ctx context.Context, txID string) error {

tx, err := r.db.BeginTx(ctx, nil)

if err != nil {

return err

}

// Store transaction for later commit/rollback

// In production, you'd need a proper transaction store

transactionStore[txID+"-"+r.name] = tx

return nil

}

func (r *DatabaseResource) Commit(ctx context.Context, txID string) error {

tx, exists := transactionStore[txID+"-"+r.name]

if !exists {

return fmt.Errorf("transaction not found: %s", txID)

}

err := tx.Commit()

delete(transactionStore, txID+"-"+r.name)

return err

}

func (r *DatabaseResource) Rollback(ctx context.Context, txID string) error {

tx, exists := transactionStore[txID+"-"+r.name]

if !exists {

return nil // Already rolled back

}

err := tx.Rollback()

delete(transactionStore, txID+"-"+r.name)

return err

}

// Global transaction store (in production, use Redis or similar)

var transactionStore = make(map[string]*sql.Tx)

func (tm *TransactionManager) ExecuteDistributedTransaction(ctx context.Context, fn func() error) error {

txID := uuid.New().String()

// Phase 1: Prepare all resources

for _, resource := range tm.resources {

if err := resource.Prepare(ctx, txID); err != nil {

// Rollback all prepared resources

tm.rollbackAll(ctx, txID)

return fmt.Errorf("prepare failed: %w", err)

}

}

// Execute business logic

if err := fn(); err != nil {

tm.rollbackAll(ctx, txID)

return fmt.Errorf("business logic failed: %w", err)

}

// Phase 2: Commit all resources

for _, resource := range tm.resources {

if err := resource.Commit(ctx, txID); err != nil {

log.Printf("Commit failed for txID %s: %v", txID, err)

// In production, you'd need a recovery mechanism here

return fmt.Errorf("commit failed: %w", err)

}

}

return nil

}

func (tm *TransactionManager) rollbackAll(ctx context.Context, txID string) {

for _, resource := range tm.resources {

if err := resource.Rollback(ctx, txID); err != nil {

log.Printf("Rollback failed for txID %s: %v", txID, err)

}

}

}

// Usage example

func ProcessDistributedOrder(ctx context.Context, request CreateOrderRequest) error {

orderDB, _ := sql.Open("mysql", "orders_connection_string")

inventoryDB, _ := sql.Open("mysql", "inventory_connection_string")

tm := &TransactionManager{

resources: []XAResource{

&DatabaseResource{db: orderDB, name: "orders"},

&DatabaseResource{db: inventoryDB, name: "inventory"},

},

}

return tm.ExecuteDistributedTransaction(ctx, func() error {

// Business logic goes here - use the prepared transactions

orderTx := transactionStore[txID+"-orders"]

inventoryTx := transactionStore[txID+"-inventory"]

// Create order

_, err := orderTx.Exec(

"INSERT INTO orders (customer_id, total_amount, status) VALUES (?, ?, ?)",

request.CustomerID, request.TotalAmount, "PENDING",

)

if err != nil {

return err

}

// Update inventory

for _, item := range request.Items {

result, err := inventoryTx.Exec(

"UPDATE inventory SET quantity = quantity - ? WHERE sku = ? AND quantity >= ?",

item.Quantity, item.SKU, item.Quantity,

)

if err != nil {

return err

}

rowsAffected, _ := result.RowsAffected()

if rowsAffected == 0 {

return fmt.Errorf("insufficient inventory for %s", item.SKU)

}

}

return nil

})

}

Concurrency Control: Optimistic vs Pessimistic

Understanding when to use optimistic versus pessimistic concurrency control can make or break your application’s performance under load.

Pessimistic Locking: “Better Safe Than Sorry”

// Java/JPA pessimistic locking

@Service

public class AccountService {

@Transactional

public void transferFunds(String fromAccountId, String toAccountId, BigDecimal amount) {

// Lock accounts in consistent order to prevent deadlocks

String firstId = fromAccountId.compareTo(toAccountId) < 0 ? fromAccountId : toAccountId;

String secondId = fromAccountId.compareTo(toAccountId) < 0 ? toAccountId : fromAccountId;

Account firstAccount = accountRepository.findById(firstId, LockModeType.PESSIMISTIC_WRITE);

Account secondAccount = accountRepository.findById(secondId, LockModeType.PESSIMISTIC_WRITE);

Account fromAccount = fromAccountId.equals(firstId) ? firstAccount : secondAccount;

Account toAccount = fromAccountId.equals(firstId) ? secondAccount : firstAccount;

if (fromAccount.getBalance().compareTo(amount) < 0) {

throw new InsufficientFundsException();

}

fromAccount.setBalance(fromAccount.getBalance().subtract(amount));

toAccount.setBalance(toAccount.getBalance().add(amount));

accountRepository.save(fromAccount);

accountRepository.save(toAccount);

}

}

// Go pessimistic locking with GORM

func (s *AccountService) TransferFunds(ctx context.Context, fromAccountID, toAccountID string, amount int64) error {

return s.WithTransaction(func(tx *gorm.DB) error {

var fromAccount, toAccount Account

// Lock accounts in consistent order

firstID, secondID := fromAccountID, toAccountID

if fromAccountID > toAccountID {

firstID, secondID = toAccountID, fromAccountID

}

// Lock first account

if err := tx.Set("gorm:query_option", "FOR UPDATE").

Where("id = ?", firstID).First(&fromAccount).Error; err != nil {

return err

}

// Lock second account

if err := tx.Set("gorm:query_option", "FOR UPDATE").

Where("id = ?", secondID).First(&toAccount).Error; err != nil {

return err

}

// Ensure we have the correct accounts

if fromAccount.ID != fromAccountID {

fromAccount, toAccount = toAccount, fromAccount

}

if fromAccount.Balance < amount {

return fmt.Errorf("insufficient funds")

}

fromAccount.Balance -= amount

toAccount.Balance += amount

if err := tx.Save(&fromAccount).Error; err != nil {

return err

}

return tx.Save(&toAccount).Error

})

}

Optimistic Locking: “Hope for the Best, Handle the Rest”

// JPA optimistic locking with version fields

@Entity

public class Account {

@Id

private String id;

private BigDecimal balance;

@Version

private Long version; // JPA automatically manages this

// getters and setters...

}

@Service

public class OptimisticAccountService {

@Transactional

@Retryable(value = {OptimisticLockingFailureException.class}, maxAttempts = 3)

public void transferFunds(String fromAccountId, String toAccountId, BigDecimal amount) {

Account fromAccount = accountRepository.findById(fromAccountId);

Account toAccount = accountRepository.findById(toAccountId);

if (fromAccount.getBalance().compareTo(amount) < 0) {

throw new InsufficientFundsException();

}

fromAccount.setBalance(fromAccount.getBalance().subtract(amount));

toAccount.setBalance(toAccount.getBalance().add(amount));

// If either account was modified by another transaction,

// OptimisticLockingFailureException will be thrown

accountRepository.save(fromAccount);

accountRepository.save(toAccount);

}

}

// Rust optimistic locking with version fields

#[derive(Queryable, Identifiable, AsChangeset)]

#[diesel(table_name = accounts)]

pub struct Account {

pub id: String,

pub balance: i64,

pub version: i32,

}

impl AccountService {

transactional! {

fn transfer_funds_optimistic(from_account_id: String, to_account_id: String, amount: i64) -> () {

use crate::schema::accounts::dsl::*;

// Read current versions

let from_account: Account = accounts

.filter(id.eq(&from_account_id))

.first(conn)

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

let to_account: Account = accounts

.filter(id.eq(&to_account_id))

.first(conn)

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

if from_account.balance < amount {

return Err(TransactionError::Business("Insufficient funds".to_string()));

}

// Update with version check

let from_updated = diesel::update(

accounts

.filter(id.eq(&from_account_id))

.filter(version.eq(from_account.version))

)

.set((

balance.eq(from_account.balance - amount),

version.eq(from_account.version + 1)

))

.execute(conn)

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

if from_updated == 0 {

return Err(TransactionError::Business("Concurrent modification detected".to_string()));

}

let to_updated = diesel::update(

accounts

.filter(id.eq(&to_account_id))

.filter(version.eq(to_account.version))

)

.set((

balance.eq(to_account.balance + amount),

version.eq(to_account.version + 1)

))

.execute(conn)

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

if to_updated == 0 {

return Err(TransactionError::Business("Concurrent modification detected".to_string()));

}

Ok(())

}

}

}

Distributed Transactions: SAGA Pattern

When 2PC becomes too heavyweight or you’re dealing with services that don’t support XA transactions, the SAGA pattern provides an elegant alternative using compensating transactions.

Command Pattern for Compensating Transactions

I initially applied this design pattern at a travel booking company in mid 2000 where we had to integrate with numerous external vendors—airline companies, hotels, car rental agencies, insurance providers, and activity booking services. Each vendor had different APIs, response times, and failure modes, but we needed to present customers with a single, atomic booking experience. The command pattern worked exceptionally well for this scenario. When a customer booked a vacation package, we’d execute a chain of commands: reserve flight, book hotel, rent car, purchase insurance. If any step failed midway through, we could automatically issue compensating transactions to undo the previous successful reservations. This approach delivered both excellent performance (operations could run in parallel where possible) and high reliability.

// Base interfaces for SAGA operations

public interface SagaCommand<T> {

T execute() throws Exception;

void compensate(T result) throws Exception;

}

public class SagaOrchestrator {

public class SagaExecution<T> {

private final SagaCommand<T> command;

private T result;

private boolean executed = false;

public SagaExecution(SagaCommand<T> command) {

this.command = command;

}

public T execute() throws Exception {

result = command.execute();

executed = true;

return result;

}

public void compensate() throws Exception {

if (executed && result != null) {

command.compensate(result);

}

}

}

private final List<SagaExecution<?>> executions = new ArrayList<>();

public <T> T execute(SagaCommand<T> command) throws Exception {

SagaExecution<T> execution = new SagaExecution<>(command);

executions.add(execution);

return execution.execute();

}

public void compensateAll() {

// Compensate in reverse order

for (int i = executions.size() - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

try {

executions.get(i).compensate();

} catch (Exception e) {

log.error("Compensation failed", e);

// In production, you'd need dead letter queue handling

}

}

}

}

// Concrete command implementations

public class CreateOrderCommand implements SagaCommand<Order> {

private final OrderService orderService;

private final CreateOrderRequest request;

public CreateOrderCommand(OrderService orderService, CreateOrderRequest request) {

this.orderService = orderService;

this.request = request;

}

@Override

public Order execute() throws Exception {

return orderService.createOrder(request);

}

@Override

public void compensate(Order order) throws Exception {

orderService.cancelOrder(order.getId());

}

}

public class ProcessPaymentCommand implements SagaCommand<Payment> {

private final PaymentService paymentService;

private final String customerId;

private final BigDecimal amount;

@Override

public Payment execute() throws Exception {

return paymentService.processPayment(customerId, amount);

}

@Override

public void compensate(Payment payment) throws Exception {

paymentService.refundPayment(payment.getId());

}

}

public class ReserveInventoryCommand implements SagaCommand<List<InventoryReservation>> {

private final InventoryService inventoryService;

private final List<OrderItem> items;

@Override

public List<InventoryReservation> execute() throws Exception {

return inventoryService.reserveItems(items);

}

@Override

public void compensate(List<InventoryReservation> reservations) throws Exception {

for (InventoryReservation reservation : reservations) {

inventoryService.releaseReservation(reservation.getId());

}

}

}

// Usage in service

@Service

public class SagaOrderService {

public void processOrderWithSaga(CreateOrderRequest request) throws Exception {

SagaOrchestrator saga = new SagaOrchestrator();

try {

// Execute commands in sequence

Order order = saga.execute(new CreateOrderCommand(orderService, request));

Payment payment = saga.execute(new ProcessPaymentCommand(

paymentService, order.getCustomerId(), order.getTotalAmount()

));

List<InventoryReservation> reservations = saga.execute(

new ReserveInventoryCommand(inventoryService, request.getItems())

);

// If we get here, everything succeeded

orderService.confirmOrder(order.getId());

} catch (Exception e) {

// Compensate all executed commands

saga.compensateAll();

throw e;

}

}

}

Persistent SAGA with State Machine

// SAGA state management

@Entity

public class SagaTransaction {

@Id

private String id;

@Enumerated(EnumType.STRING)

private SagaStatus status;

private String currentStep;

@ElementCollection

private List<String> completedSteps = new ArrayList<>();

@ElementCollection

private List<String> compensatedSteps = new ArrayList<>();

private String contextData; // JSON serialized context

// getters/setters...

}

public enum SagaStatus {

STARTED, IN_PROGRESS, COMPLETED, COMPENSATING, COMPENSATED, FAILED

}

@Component

public class PersistentSagaOrchestrator {

@Autowired

private SagaTransactionRepository sagaRepo;

@Transactional

public void executeSaga(String sagaId, List<SagaStep> steps) {

SagaTransaction saga = sagaRepo.findById(sagaId)

.orElse(new SagaTransaction(sagaId));

try {

for (SagaStep step : steps) {

if (saga.getCompletedSteps().contains(step.getName())) {

continue; // Already completed

}

saga.setCurrentStep(step.getName());

saga.setStatus(SagaStatus.IN_PROGRESS);

sagaRepo.save(saga);

// Execute step

step.execute();

saga.getCompletedSteps().add(step.getName());

sagaRepo.save(saga);

}

saga.setStatus(SagaStatus.COMPLETED);

sagaRepo.save(saga);

} catch (Exception e) {

compensateSaga(sagaId);

throw e;

}

}

@Transactional

public void compensateSaga(String sagaId) {

SagaTransaction saga = sagaRepo.findById(sagaId)

.orElseThrow(() -> new IllegalArgumentException("SAGA not found"));

saga.setStatus(SagaStatus.COMPENSATING);

sagaRepo.save(saga);

// Compensate in reverse order

List<String> stepsToCompensate = new ArrayList<>(saga.getCompletedSteps());

Collections.reverse(stepsToCompensate);

for (String stepName : stepsToCompensate) {

if (saga.getCompensatedSteps().contains(stepName)) {

continue;

}

try {

SagaStep step = findStepByName(stepName);

step.compensate();

saga.getCompensatedSteps().add(stepName);

sagaRepo.save(saga);

} catch (Exception e) {

log.error("Compensation failed for step: " + stepName, e);

saga.setStatus(SagaStatus.FAILED);

sagaRepo.save(saga);

return;

}

}

saga.setStatus(SagaStatus.COMPENSATED);

sagaRepo.save(saga);

}

}

Go SAGA Implementation

// SAGA state machine in Go

package saga

import (

"context"

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"time"

"gorm.io/gorm"

)

type SagaStatus string

const (

StatusStarted SagaStatus = "STARTED"

StatusInProgress SagaStatus = "IN_PROGRESS"

StatusCompleted SagaStatus = "COMPLETED"

StatusCompensating SagaStatus = "COMPENSATING"

StatusCompensated SagaStatus = "COMPENSATED"

StatusFailed SagaStatus = "FAILED"

)

type SagaTransaction struct {

ID string `gorm:"primarykey"`

Status SagaStatus

CurrentStep string

CompletedSteps string // JSON array

CompensatedSteps string // JSON array

ContextData string // JSON context

CreatedAt time.Time

UpdatedAt time.Time

}

type SagaStep interface {

Name() string

Execute(ctx context.Context, sagaContext map[string]interface{}) error

Compensate(ctx context.Context, sagaContext map[string]interface{}) error

}

type SagaOrchestrator struct {

db *gorm.DB

}

func NewSagaOrchestrator(db *gorm.DB) *SagaOrchestrator {

return &SagaOrchestrator{db: db}

}

func (o *SagaOrchestrator) ExecuteSaga(ctx context.Context, sagaID string, steps []SagaStep, context map[string]interface{}) error {

return o.db.Transaction(func(tx *gorm.DB) error {

var saga SagaTransaction

if err := tx.First(&saga, "id = ?", sagaID).Error; err != nil {

if err == gorm.ErrRecordNotFound {

// Create new saga

contextJSON, _ := json.Marshal(context)

saga = SagaTransaction{

ID: sagaID,

Status: StatusStarted,

ContextData: string(contextJSON),

}

if err := tx.Create(&saga).Error; err != nil {

return err

}

} else {

return err

}

}

// Parse completed steps

var completedSteps []string

if saga.CompletedSteps != "" {

json.Unmarshal([]byte(saga.CompletedSteps), &completedSteps)

}

completedMap := make(map[string]bool)

for _, step := range completedSteps {

completedMap[step] = true

}

// Execute steps

for _, step := range steps {

if completedMap[step.Name()] {

continue // Already completed

}

saga.CurrentStep = step.Name()

saga.Status = StatusInProgress

if err := tx.Save(&saga).Error; err != nil {

return err

}

// Parse saga context

var sagaContext map[string]interface{}

json.Unmarshal([]byte(saga.ContextData), &sagaContext)

// Execute step

if err := step.Execute(ctx, sagaContext); err != nil {

// Start compensation

return o.compensateSaga(ctx, tx, sagaID, steps[:len(completedSteps)])

}

// Mark step as completed

completedSteps = append(completedSteps, step.Name())

completedJSON, _ := json.Marshal(completedSteps)

saga.CompletedSteps = string(completedJSON)

// Update context if modified

updatedContext, _ := json.Marshal(sagaContext)

saga.ContextData = string(updatedContext)

if err := tx.Save(&saga).Error; err != nil {

return err

}

}

saga.Status = StatusCompleted

return tx.Save(&saga).Error

})

}

func (o *SagaOrchestrator) compensateSaga(ctx context.Context, tx *gorm.DB, sagaID string, completedSteps []SagaStep) error {

var saga SagaTransaction

if err := tx.First(&saga, "id = ?", sagaID).Error; err != nil {

return err

}

saga.Status = StatusCompensating

if err := tx.Save(&saga).Error; err != nil {

return err

}

// Parse compensated steps

var compensatedSteps []string

if saga.CompensatedSteps != "" {

json.Unmarshal([]byte(saga.CompensatedSteps), &compensatedSteps)

}

compensatedMap := make(map[string]bool)

for _, step := range compensatedSteps {

compensatedMap[step] = true

}

// Compensate in reverse order

for i := len(completedSteps) - 1; i >= 0; i-- {

step := completedSteps[i]

if compensatedMap[step.Name()] {

continue

}

var sagaContext map[string]interface{}

json.Unmarshal([]byte(saga.ContextData), &sagaContext)

if err := step.Compensate(ctx, sagaContext); err != nil {

saga.Status = StatusFailed

tx.Save(&saga)

return fmt.Errorf("compensation failed for step %s: %w", step.Name(), err)

}

compensatedSteps = append(compensatedSteps, step.Name())

compensatedJSON, _ := json.Marshal(compensatedSteps)

saga.CompensatedSteps = string(compensatedJSON)

if err := tx.Save(&saga).Error; err != nil {

return err

}

}

saga.Status = StatusCompensated

return tx.Save(&saga).Error

}

// Concrete step implementations

type CreateOrderStep struct {

orderService *OrderService

request CreateOrderRequest

}

func (s *CreateOrderStep) Name() string {

return "CREATE_ORDER"

}

func (s *CreateOrderStep) Execute(ctx context.Context, sagaContext map[string]interface{}) error {

order, err := s.orderService.CreateOrder(ctx, s.request)

if err != nil {

return err

}

// Store order ID in context for later steps

sagaContext["orderId"] = order.ID

return nil

}

func (s *CreateOrderStep) Compensate(ctx context.Context, sagaContext map[string]interface{}) error {

if orderID, exists := sagaContext["orderId"]; exists {

return s.orderService.CancelOrder(ctx, orderID.(uint))

}

return nil

}

// Usage

func ProcessOrderWithSaga(ctx context.Context, orchestrator *SagaOrchestrator, request CreateOrderRequest) error {

sagaID := uuid.New().String()

steps := []SagaStep{

&CreateOrderStep{orderService, request},

&ProcessPaymentStep{paymentService, request.CustomerID, request.TotalAmount},

&ReserveInventoryStep{inventoryService, request.Items},

}

context := map[string]interface{}{

"customerId": request.CustomerID,

"requestId": request.RequestID,

}

return orchestrator.ExecuteSaga(ctx, sagaID, steps, context)

}

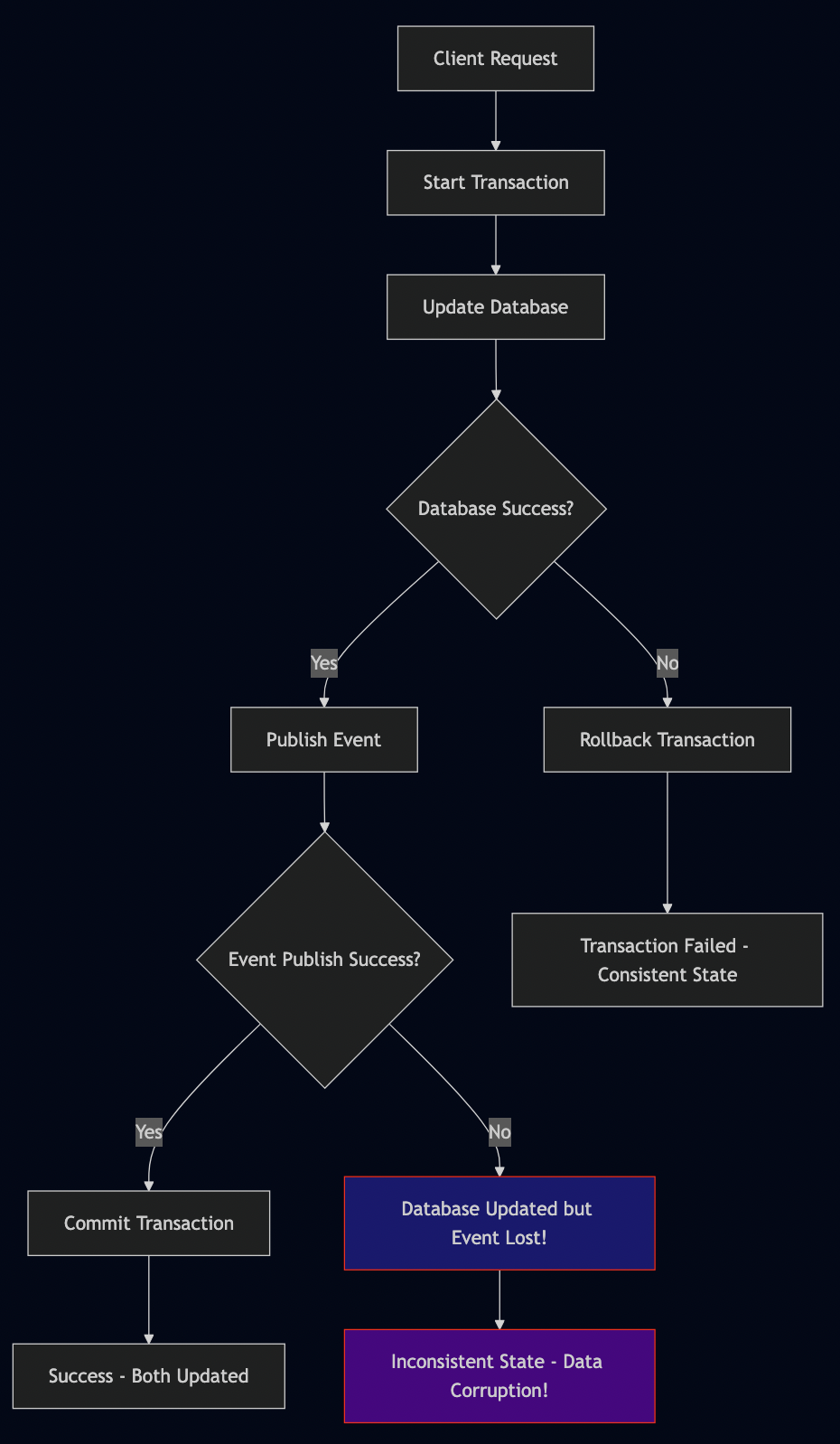

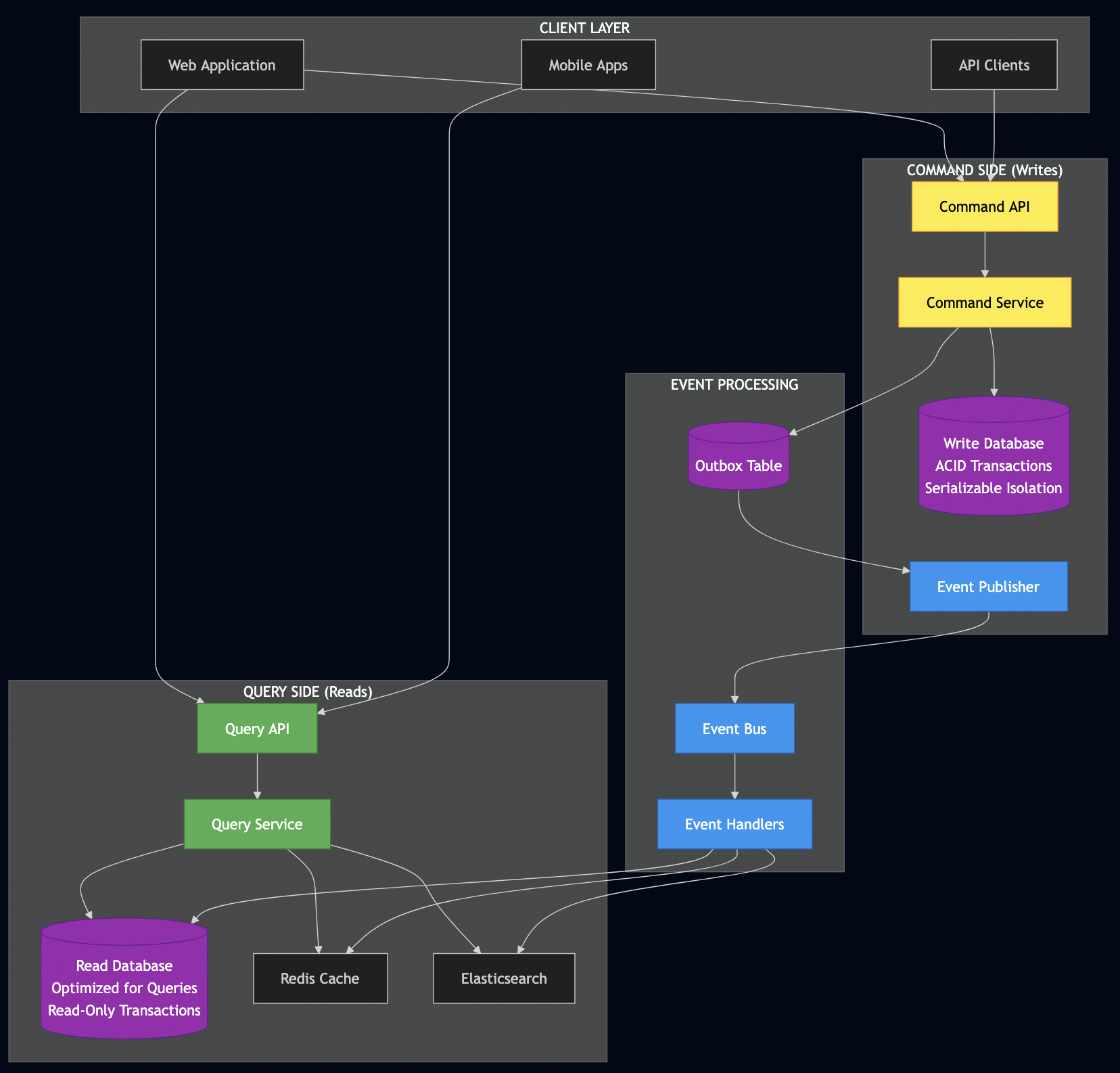

The Dual-Write Problem: Database + Events

One of the most insidious transaction problems occurs when you need to both update the database and publish an event. I’ve debugged countless production issues where customers received order confirmations but no order existed in the database, or orders were created but notification events never fired.

The Anti-Pattern: Sequential Operations

// THIS IS FUNDAMENTALLY BROKEN - DON'T DO THIS

@Service

public class BrokenOrderService {

@Transactional

public void processOrder(CreateOrderRequest request) {

Order order = orderRepository.save(new Order(request));

// DANGER: Event published outside transaction boundary

eventPublisher.publishEvent(new OrderCreatedEvent(order));

// What if this line throws an exception?

// Event is already published but transaction will rollback!

}

// ALSO BROKEN: Event first, then database

@Transactional

public void processOrderEventFirst(CreateOrderRequest request) {

Order order = new Order(request);

// DANGER: Event published before persistence

eventPublisher.publishEvent(new OrderCreatedEvent(order));

// What if database save fails?

// Event consumers will query for order that doesn't exist!

orderRepository.save(order);

}

}

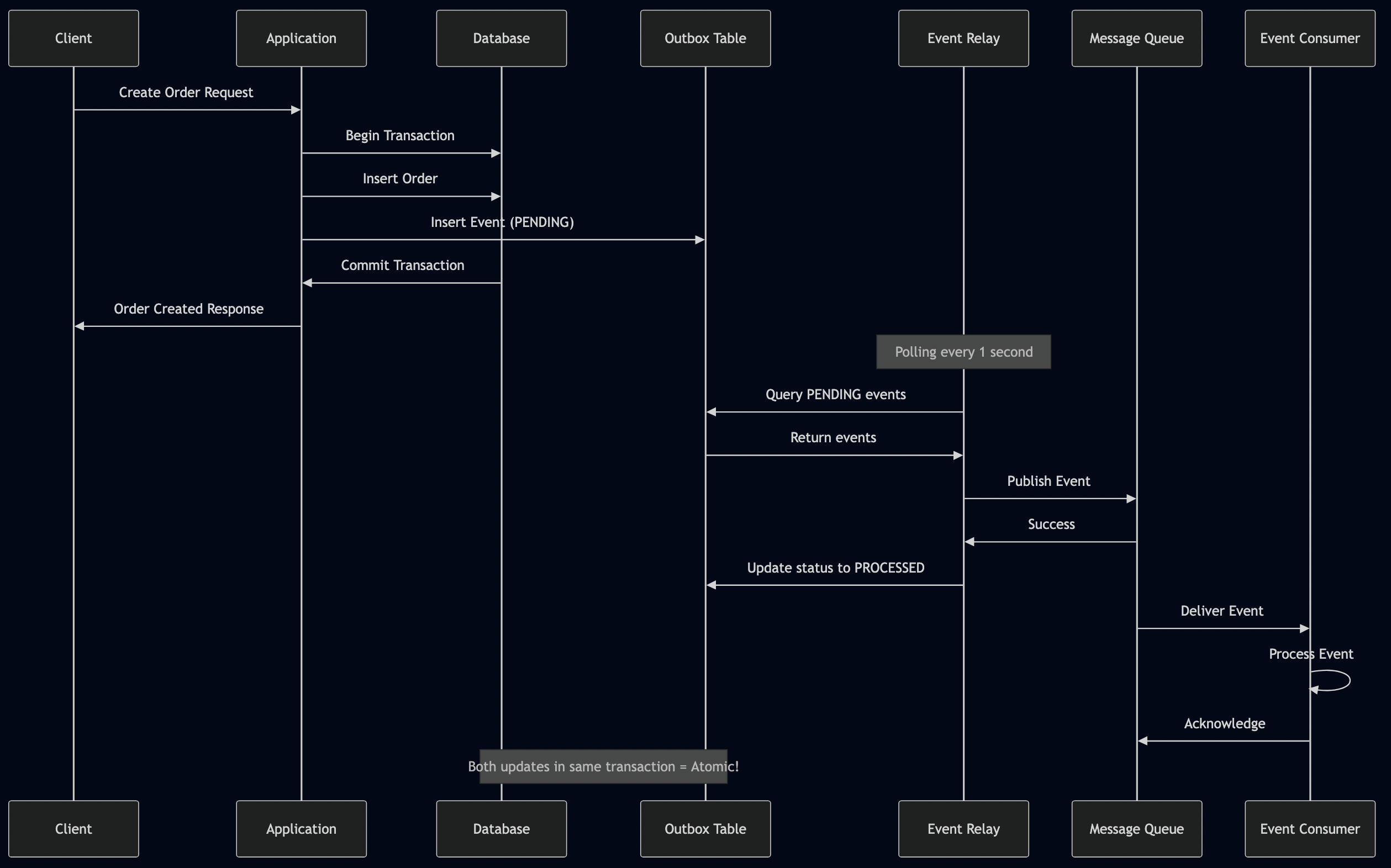

Solution 1: Transactional Outbox Pattern

I have used Outbox pattern in a number of applications especially for sending notifications to users where instead of directly sending an event to a queue, the messages are stored in the database and then relayed to external service like Apple Push Notification Service (APNs) or Google Push Notification Service (FCM).

// Outbox event entity

@Entity

@Table(name = "outbox_events")

public class OutboxEvent {

@Id

private String id;

@Column(name = "event_type")

private String eventType;

@Column(name = "payload", columnDefinition = "TEXT")

private String payload;

@Column(name = "created_at")

private Instant createdAt;

@Column(name = "processed_at")

private Instant processedAt;

@Enumerated(EnumType.STRING)

private OutboxStatus status;

// constructors, getters, setters...

}

public enum OutboxStatus {

PENDING, PROCESSED, FAILED

}

// Outbox repository

@Repository

public interface OutboxEventRepository extends JpaRepository<OutboxEvent, String> {

@Query("SELECT e FROM OutboxEvent e WHERE e.status = :status ORDER BY e.createdAt ASC")

List<OutboxEvent> findByStatusOrderByCreatedAt(@Param("status") OutboxStatus status);

@Modifying

@Query("UPDATE OutboxEvent e SET e.status = :status, e.processedAt = :processedAt WHERE e.id = :id")

void updateStatus(@Param("id") String id, @Param("status") OutboxStatus status, @Param("processedAt") Instant processedAt);

}

// Corrected order service using outbox

@Service

public class TransactionalOrderService {

@Autowired

private OrderRepository orderRepository;

@Autowired

private OutboxEventRepository outboxRepository;

@Transactional

public void processOrder(CreateOrderRequest request) {

// 1. Process business logic

Order order = new Order(request);

order = orderRepository.save(order);

// 2. Store event in same transaction

OutboxEvent event = new OutboxEvent(

UUID.randomUUID().toString(),

"OrderCreated",

serializeEvent(new OrderCreatedEvent(order)),

Instant.now(),

OutboxStatus.PENDING

);

outboxRepository.save(event);

// Both order and event are committed atomically!

}

private String serializeEvent(Object event) {

try {

return objectMapper.writeValueAsString(event);

} catch (JsonProcessingException e) {

throw new RuntimeException("Event serialization failed", e);

}

}

}

// Event relay service

@Component

public class OutboxEventRelay {

@Autowired

private OutboxEventRepository outboxRepository;

@Autowired

private ApplicationEventPublisher eventPublisher;

@Scheduled(fixedDelay = 1000) // Poll every second

@Transactional

public void processOutboxEvents() {

List<OutboxEvent> pendingEvents = outboxRepository

.findByStatusOrderByCreatedAt(OutboxStatus.PENDING);

for (OutboxEvent outboxEvent : pendingEvents) {

try {

// Deserialize and publish the event

Object event = deserializeEvent(outboxEvent.getEventType(), outboxEvent.getPayload());

eventPublisher.publishEvent(event);

// Mark as processed

outboxRepository.updateStatus(

outboxEvent.getId(),

OutboxStatus.PROCESSED,

Instant.now()

);

} catch (Exception e) {

log.error("Failed to process outbox event: " + outboxEvent.getId(), e);

outboxRepository.updateStatus(

outboxEvent.getId(),

OutboxStatus.FAILED,

Instant.now()

);

}

}

}

}

Go Implementation: Outbox Pattern with GORM

// Outbox event model

type OutboxEvent struct {

ID string `gorm:"primarykey"`

EventType string `gorm:"not null"`

Payload string `gorm:"type:text;not null"`

CreatedAt time.Time

ProcessedAt *time.Time

Status OutboxStatus `gorm:"type:varchar(20);default:'PENDING'"`

}

type OutboxStatus string

const (

OutboxStatusPending OutboxStatus = "PENDING"

OutboxStatusProcessed OutboxStatus = "PROCESSED"

OutboxStatusFailed OutboxStatus = "FAILED"

)

// Service with outbox pattern

type OrderService struct {

db *gorm.DB

eventRelay *OutboxEventRelay

}

func (s *OrderService) ProcessOrder(ctx context.Context, request CreateOrderRequest) (*Order, error) {

var order *Order

err := s.db.Transaction(func(tx *gorm.DB) error {

// 1. Create order

order = &Order{

CustomerID: request.CustomerID,

TotalAmount: request.TotalAmount,

Status: "CONFIRMED",

}

if err := tx.Create(order).Error; err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to create order: %w", err)

}

// 2. Store event in same transaction

eventPayload, err := json.Marshal(OrderCreatedEvent{

OrderID: order.ID,

CustomerID: order.CustomerID,

TotalAmount: order.TotalAmount,

})

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to serialize event: %w", err)

}

outboxEvent := &OutboxEvent{

ID: uuid.New().String(),

EventType: "OrderCreated",

Payload: string(eventPayload),

CreatedAt: time.Now(),

Status: OutboxStatusPending,

}

if err := tx.Create(outboxEvent).Error; err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to store outbox event: %w", err)

}

return nil

})

return order, err

}

// Event relay service

type OutboxEventRelay struct {

db *gorm.DB

eventPublisher EventPublisher

ticker *time.Ticker

done chan bool

}

func NewOutboxEventRelay(db *gorm.DB, publisher EventPublisher) *OutboxEventRelay {

return &OutboxEventRelay{

db: db,

eventPublisher: publisher,

ticker: time.NewTicker(1 * time.Second),

done: make(chan bool),

}

}

func (r *OutboxEventRelay) Start(ctx context.Context) {

go func() {

for {

select {

case <-r.ticker.C:

r.processOutboxEvents(ctx)

case <-r.done:

return

case <-ctx.Done():

return

}

}

}()

}

func (r *OutboxEventRelay) processOutboxEvents(ctx context.Context) {

var events []OutboxEvent

// Find pending events

if err := r.db.Where("status = ?", OutboxStatusPending).

Order("created_at ASC").

Limit(100).

Find(&events).Error; err != nil {

log.Printf("Failed to fetch outbox events: %v", err)

return

}

for _, event := range events {

if err := r.processEvent(ctx, event); err != nil {

log.Printf("Failed to process event %s: %v", event.ID, err)

// Mark as failed

now := time.Now()

r.db.Model(&event).Updates(OutboxEvent{

Status: OutboxStatusFailed,

ProcessedAt: &now,

})

} else {

// Mark as processed

now := time.Now()

r.db.Model(&event).Updates(OutboxEvent{

Status: OutboxStatusProcessed,

ProcessedAt: &now,

})

}

}

}

func (r *OutboxEventRelay) processEvent(ctx context.Context, event OutboxEvent) error {

// Deserialize and publish the event

switch event.EventType {

case "OrderCreated":

var orderEvent OrderCreatedEvent

if err := json.Unmarshal([]byte(event.Payload), &orderEvent); err != nil {

return err

}

return r.eventPublisher.Publish(ctx, orderEvent)

default:

return fmt.Errorf("unknown event type: %s", event.EventType)

}

}

Rust Implementation: Outbox with Diesel

// Outbox event model

use diesel::prelude::*;

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

use chrono::{DateTime, Utc};

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Queryable, Insertable, Serialize, Deserialize)]

#[diesel(table_name = outbox_events)]

pub struct OutboxEvent {

pub id: String,

pub event_type: String,

pub payload: String,

pub created_at: DateTime<Utc>,

pub processed_at: Option<DateTime<Utc>>,

pub status: OutboxStatus,

}

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Serialize, Deserialize, diesel_derive_enum::DbEnum)]

#[ExistingTypePath = "crate::schema::sql_types::OutboxStatus"]

pub enum OutboxStatus {

Pending,

Processed,

Failed,

}

// Service with outbox

impl OrderService {

transactional! {

fn process_order_with_outbox(request: CreateOrderRequest) -> Order {

use crate::schema::orders::dsl::*;

use crate::schema::outbox_events::dsl::*;

// 1. Create order

let new_order = NewOrder {

customer_id: &request.customer_id,

total_amount: request.total_amount,

status: "CONFIRMED",

};

let order: Order = diesel::insert_into(orders)

.values(&new_order)

.get_result(conn)

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

// 2. Create event in same transaction

let event_payload = serde_json::to_string(&OrderCreatedEvent {

order_id: order.id,

customer_id: order.customer_id.clone(),

total_amount: order.total_amount,

}).map_err(|e| TransactionError::Business(format!("Event serialization failed: {}", e)))?;

let outbox_event = OutboxEvent {

id: uuid::Uuid::new_v4().to_string(),

event_type: "OrderCreated".to_string(),

payload: event_payload,

created_at: Utc::now(),

processed_at: None,

status: OutboxStatus::Pending,

};

diesel::insert_into(outbox_events)

.values(&outbox_event)

.execute(conn)

.map_err(TransactionError::Database)?;

Ok(order)

}

}

}

// Event relay service

pub struct OutboxEventRelay {

pool: Pool<ConnectionManager<PgConnection>>,

event_publisher: Arc<dyn EventPublisher>,

}

impl OutboxEventRelay {

pub async fn start(&self, mut shutdown: tokio::sync::broadcast::Receiver<()>) {

let mut interval = tokio::time::interval(Duration::from_secs(1));

loop {

tokio::select! {

_ = interval.tick() => {

if let Err(e) = self.process_outbox_events().await {

tracing::error!("Failed to process outbox events: {}", e);

}

}

_ = shutdown.recv() => {

tracing::info!("Outbox relay shutting down");

break;

}

}

}

}

async fn process_outbox_events(&self) -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

use crate::schema::outbox_events::dsl::*;

let mut conn = self.pool.get()?;

let pending_events: Vec<OutboxEvent> = outbox_events

.filter(status.eq(OutboxStatus::Pending))

.order(created_at.asc())

.limit(100)

.load(&mut conn)?;

for event in pending_events {

match self.process_single_event(&event).await {

Ok(_) => {

// Mark as processed

let now = Utc::now();

diesel::update(outbox_events.filter(id.eq(&event.id)))

.set((

status.eq(OutboxStatus::Processed),

processed_at.eq(Some(now))

))

.execute(&mut conn)?;

}

Err(e) => {

tracing::error!("Failed to process event {}: {}", event.id, e);

let now = Utc::now();

diesel::update(outbox_events.filter(id.eq(&event.id)))

.set((

status.eq(OutboxStatus::Failed),

processed_at.eq(Some(now))

))

.execute(&mut conn)?;

}

}

}

Ok(())

}

}

Solution 2: Change Data Capture (CDC)

I have used this pattern extensively for high-throughput systems where polling-based outbox patterns couldn’t keep up with the data volume. My first implementation was in the early 2000s when building an intelligent traffic management system, where I used CDC to synchronize data between two subsystems—all database changes were captured and published to a JMS queue, with consumers updating their local databases in near real-time. In subsequent projects, I used CDC to publish database changes directly to Kafka topics, enabling downstream services to build analytical systems, populate data lakes, and power real-time reporting dashboards.

As CDC eliminates the polling overhead entirely, this approach can be scaled to millions of transactions per day while maintaining sub-second latency for downstream consumers.

// CDC-based event publisher using Debezium

@Component

public class CDCEventHandler {

@Autowired

private KafkaTemplate<String, String> kafkaTemplate;

@KafkaListener(topics = "dbserver.public.orders")

public void handleOrderChange(ConsumerRecord<String, String> record) {

try {

// Parse CDC event

JsonNode changeEvent = objectMapper.readTree(record.value());

String operation = changeEvent.get("op").asText(); // c=create, u=update, d=delete

if ("c".equals(operation)) {

JsonNode after = changeEvent.get("after");

OrderCreatedEvent event = OrderCreatedEvent.builder()

.orderId(after.get("id").asLong())

.customerId(after.get("customer_id").asText())

.totalAmount(after.get("total_amount").asLong())

.build();

// Publish to business event topic

kafkaTemplate.send("order-events",

event.getOrderId().toString(),

objectMapper.writeValueAsString(event));

}

} catch (Exception e) {

log.error("Failed to process CDC event", e);

}

}

}

Solution 3: Event Sourcing

I have often used this pattern with financial systems in conjunction with CQRS, where all changes are stored as immutable events and can be replayed if needed. This approach is particularly valuable in financial contexts because it provides a complete audit trail—every account balance change, every trade, every adjustment can be traced back to its originating event.

For systems where events are the source of truth:

// Event store as the primary persistence

@Entity

public class EventStore {

@Id

private String eventId;

private String aggregateId;

private String eventType;

private String eventData;

private Long version;

private Instant timestamp;

// getters, setters...

}

@Service

public class EventSourcedOrderService {

@Transactional

public void processOrder(CreateOrderRequest request) {

String orderId = UUID.randomUUID().toString();

// Store event - this IS the transaction