Over the last year, I have been applying Agentic AI to various problems at work and to improve personal productivity. For example, every morning, I faced the same challenge: information overload.

My typical morning looked like this:

- ? Check emails and sort out what’s important

- ? Check my calendar and figure out which ones are critical

- ? Skim HackerNews, TechCrunch, newsletters for any important insight

- ? Check Slack for any critical updates

- ?? Look up weather ? Should I bring an umbrella or jacket?

- ? Already lost 45 minutes just gathering information!

I needed an AI assistant that could digest all this information while I shower, then present me with a personalized 3-minute brief highlighting what actually matters. Also, following were key constraints for this assistant:

- ? Complete privacy – My emails and calendar shouldn’t leave my laptop and I didn’t want to run any MCP servers in cloud that could expose my private credentials

- ? Zero ongoing costs – Running complex Agentic workflow on the hosted environments could easily cost me hundreds of dollars a month

- ? Fast iteration – Test changes instantly during development

- ? Flexible deployment – Start local, deploy to cloud when ready

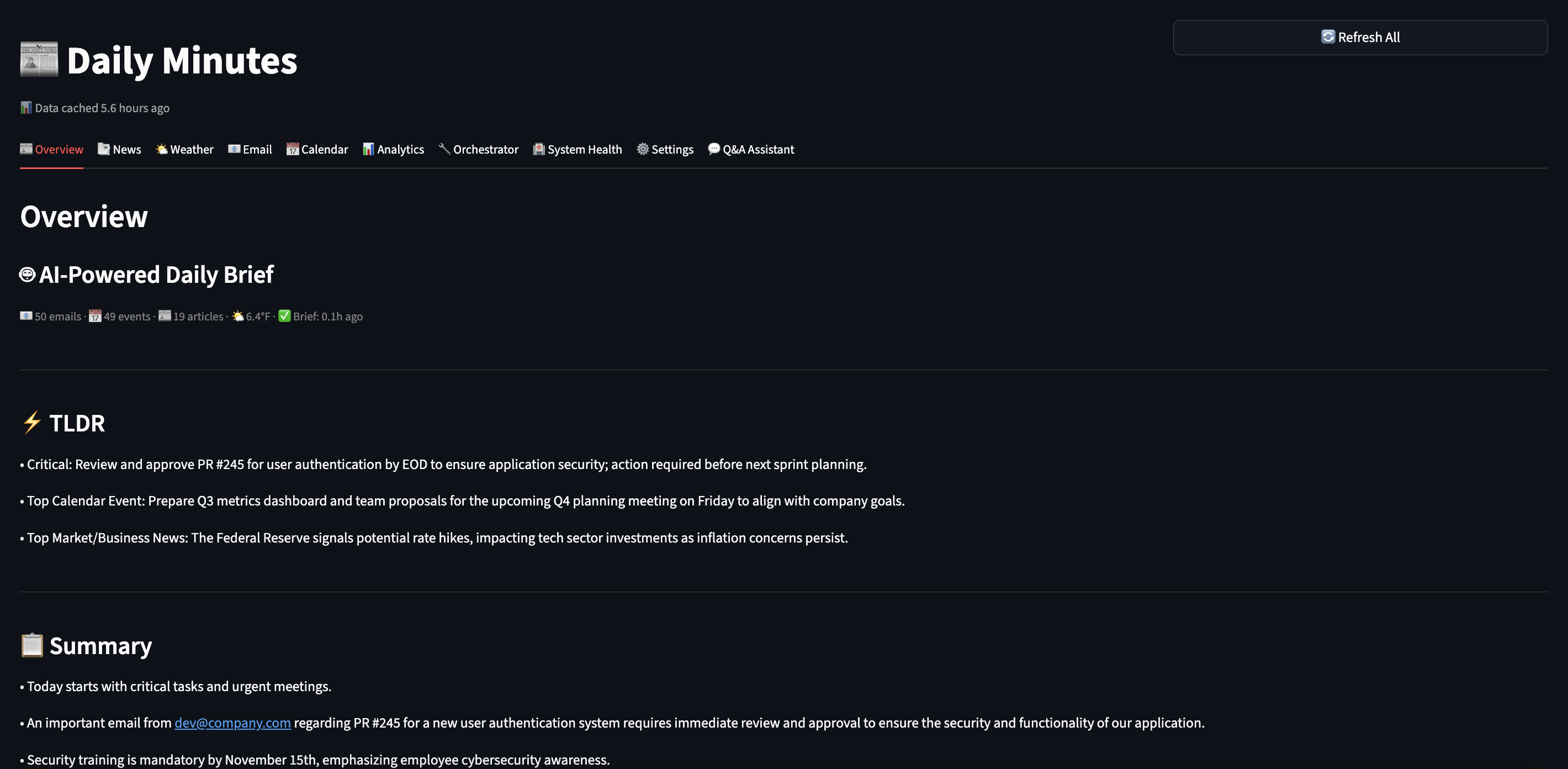

I will walk through my journey of building Daily Minutes with Claude Code – a fully functional agentic AI system that runs on my laptop using local LLMs, saves me 30 minutes every morning.

Agentic Building Blocks

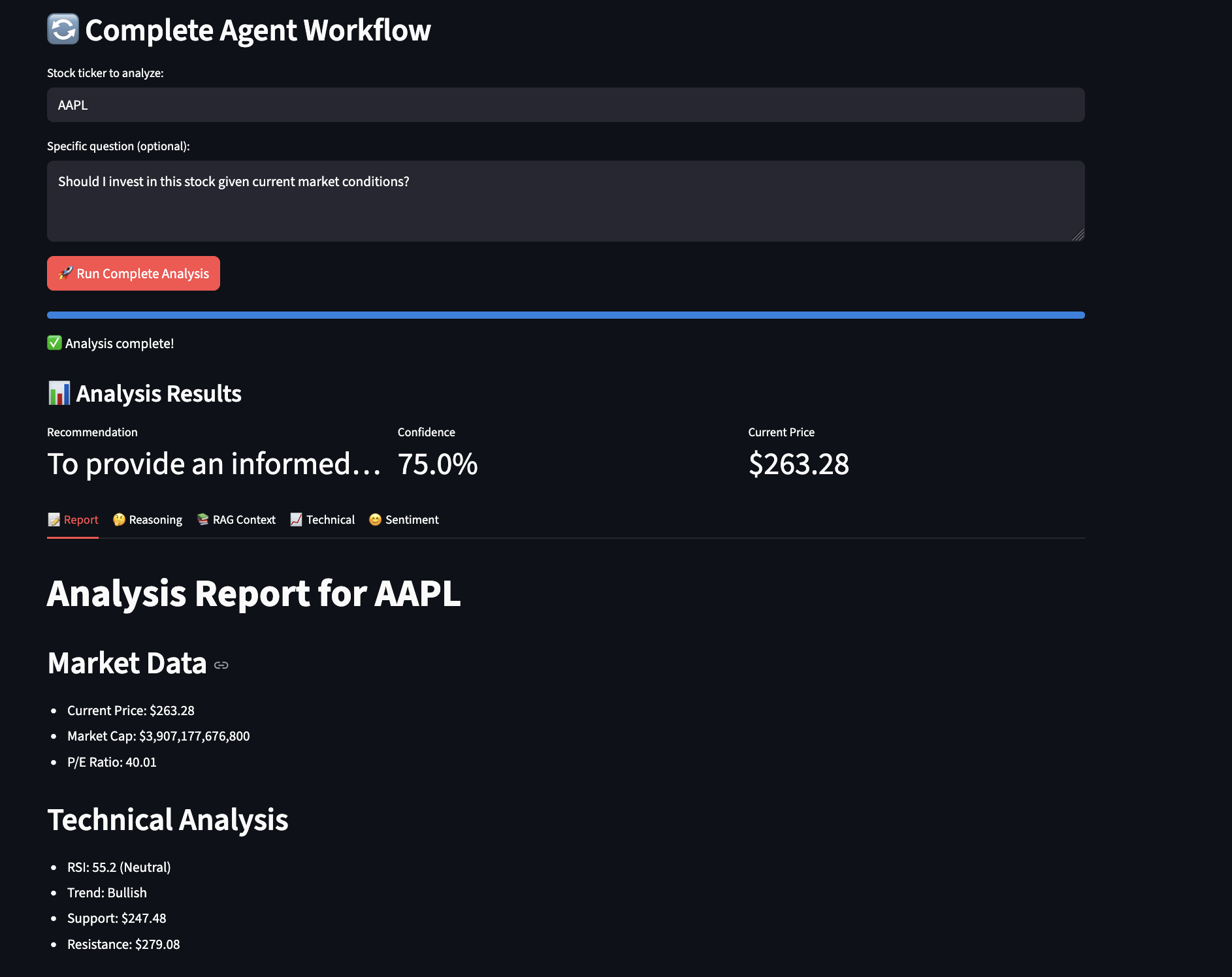

I applied following building blocks to create this system:

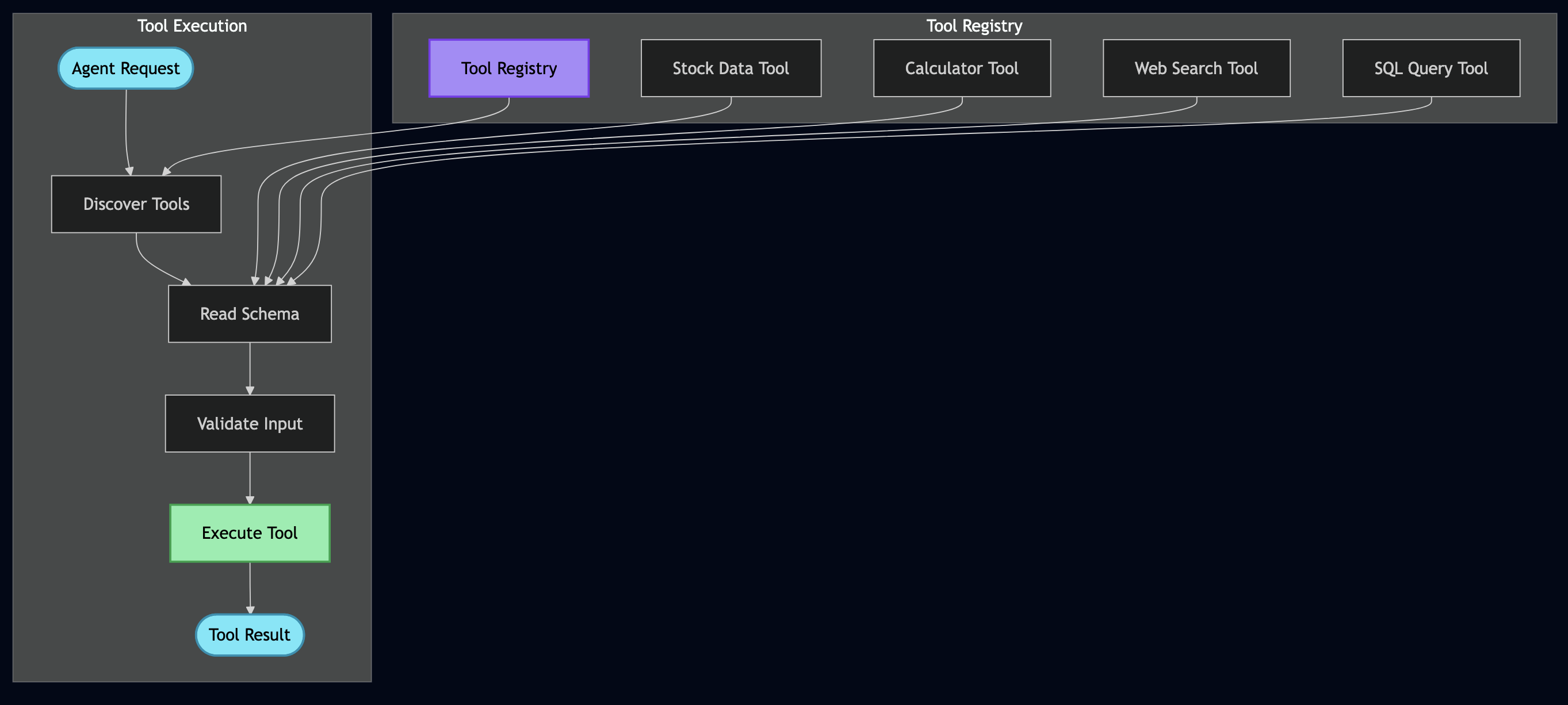

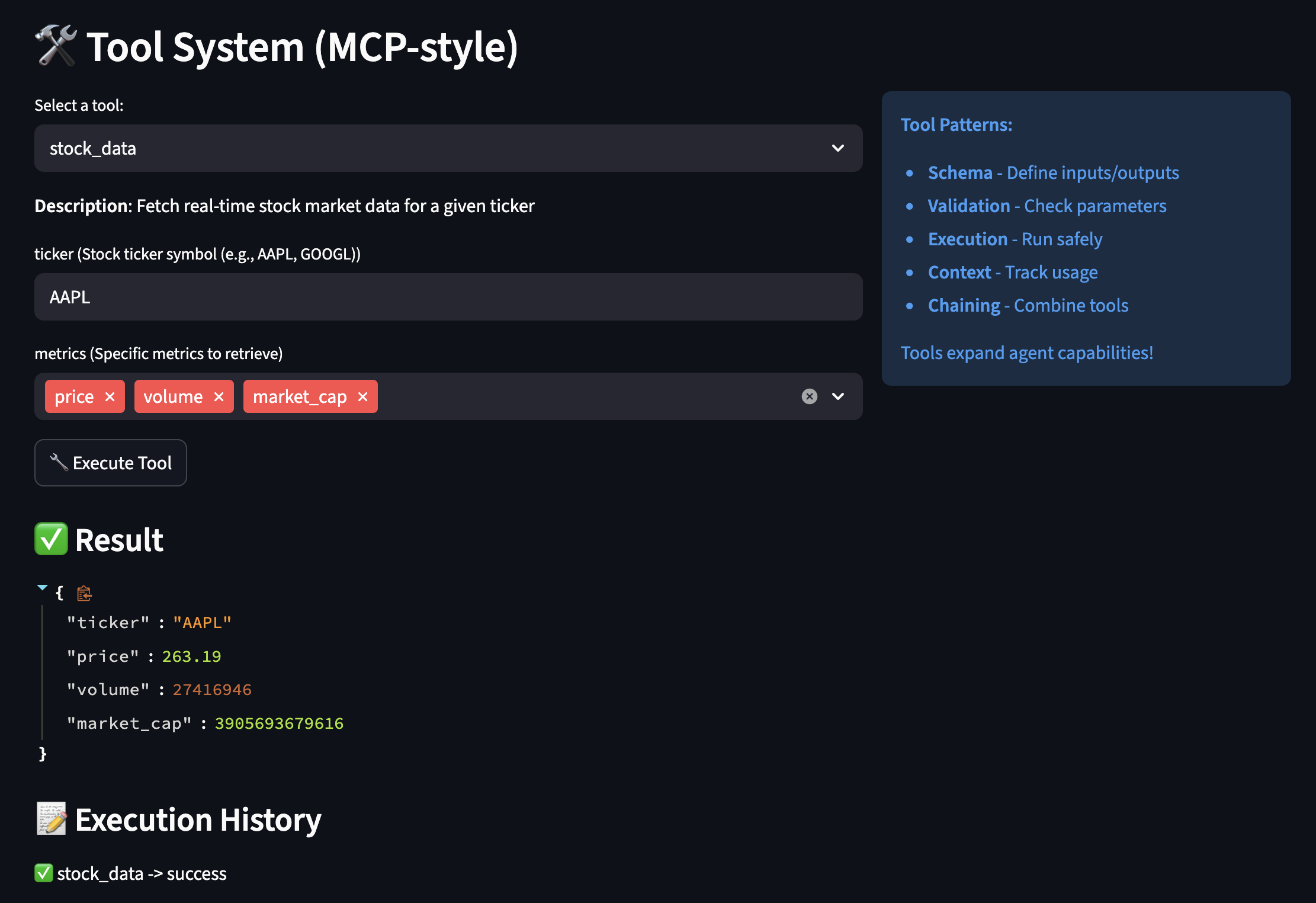

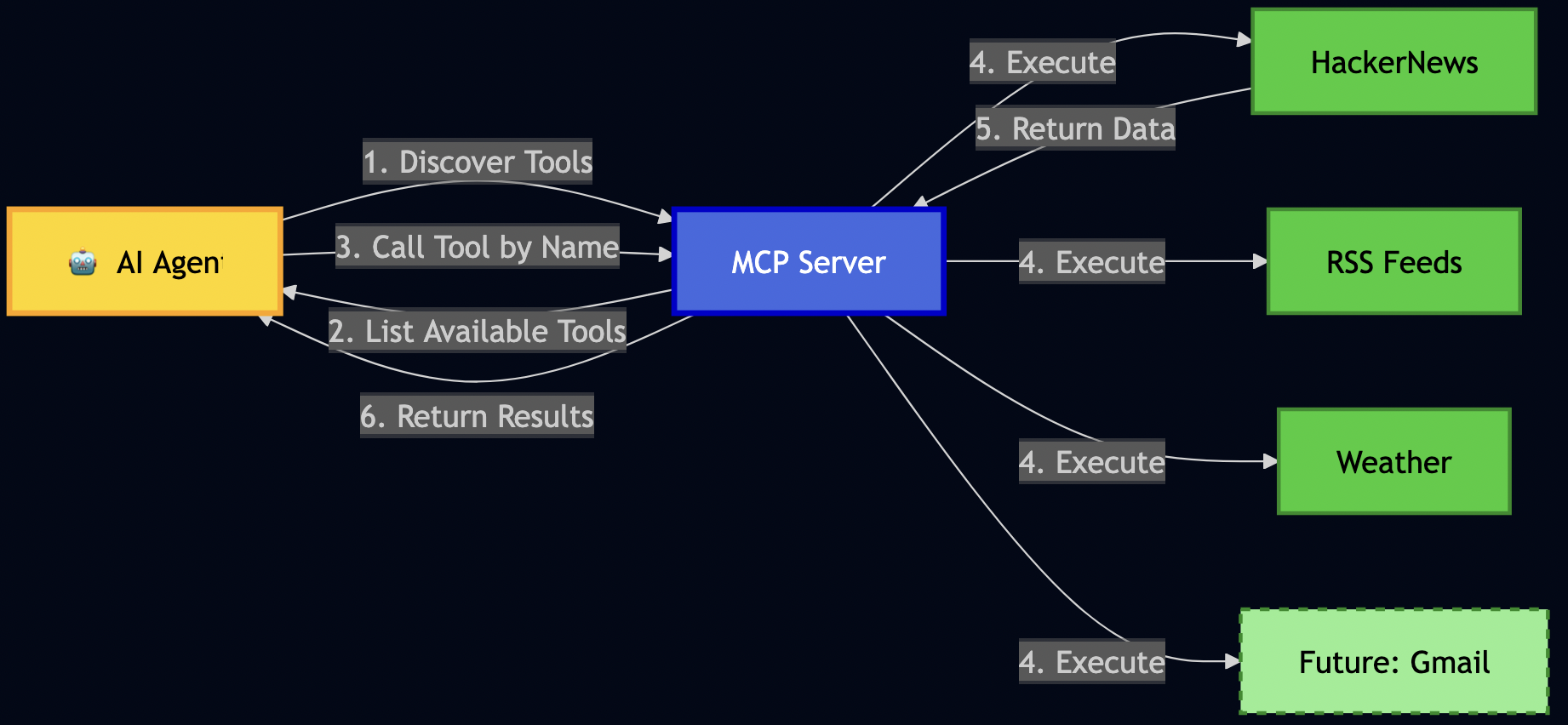

- MCP (Model Context Protocol) – connecting to data sources discoverable by AI

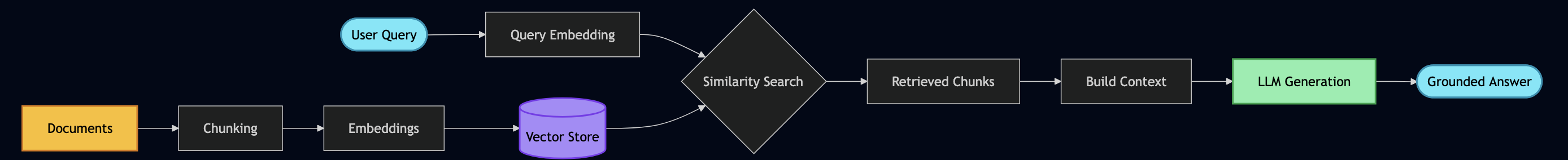

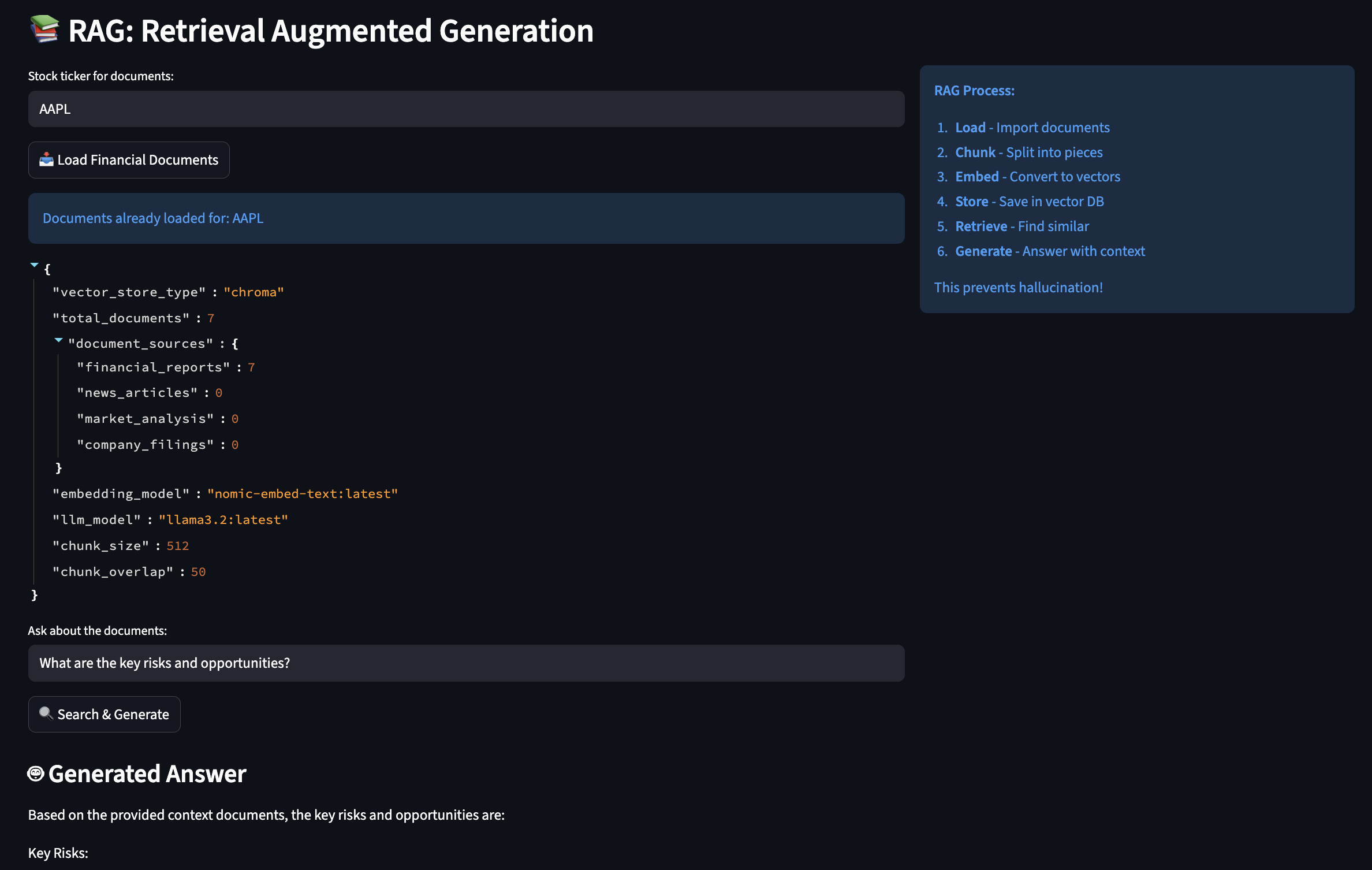

- RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) – give AI long-term memory

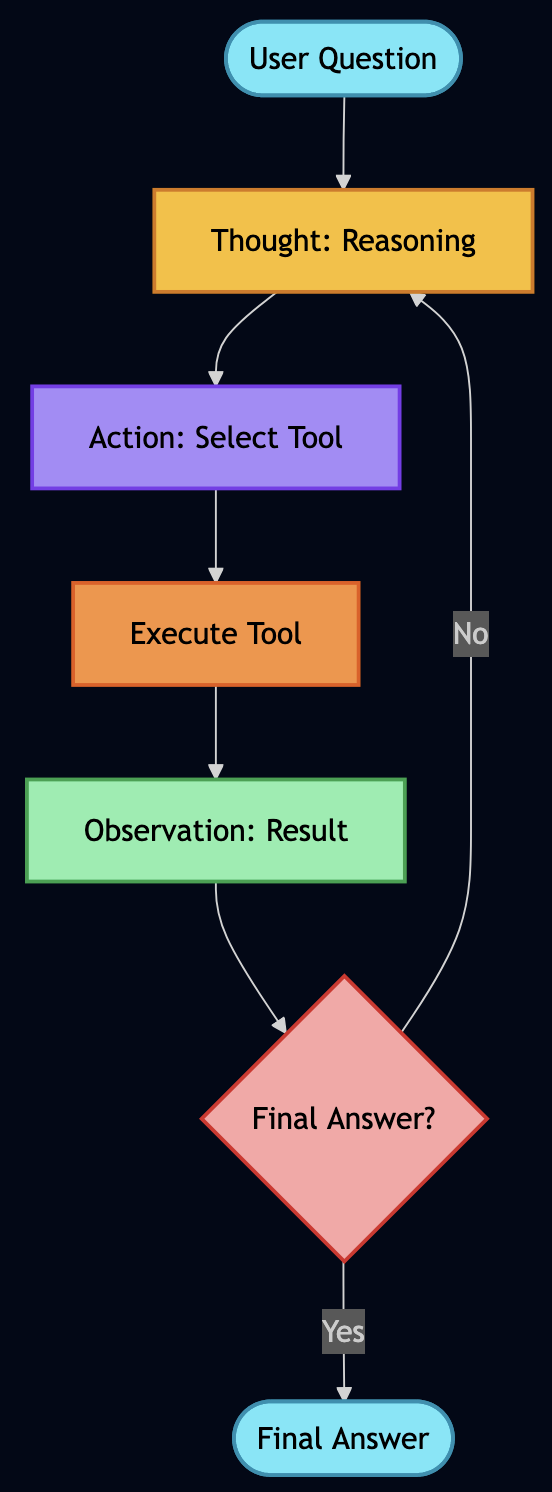

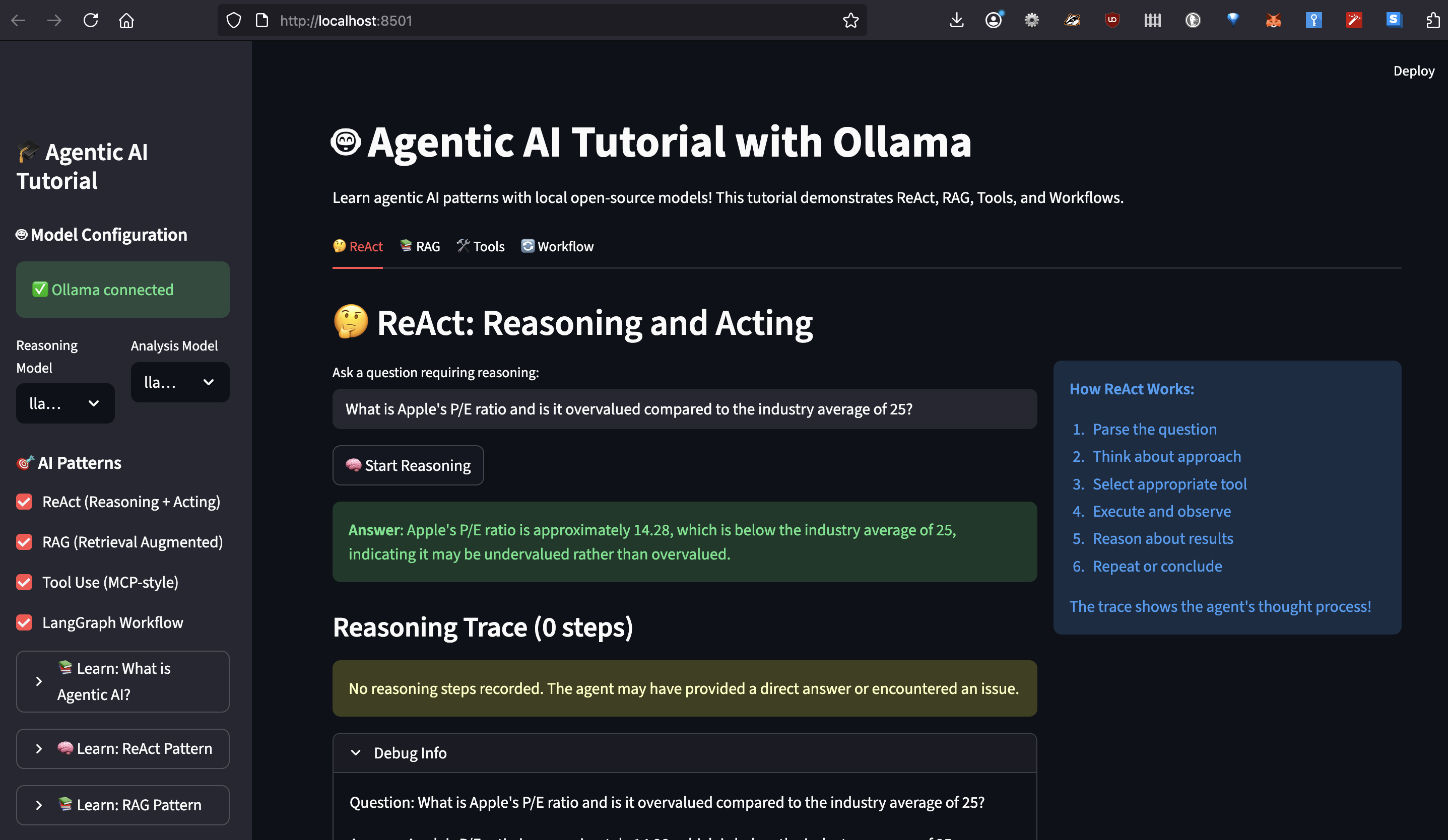

- ReAct Pattern – teach AI to reason before acting

- RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) – teach AI from my preferences

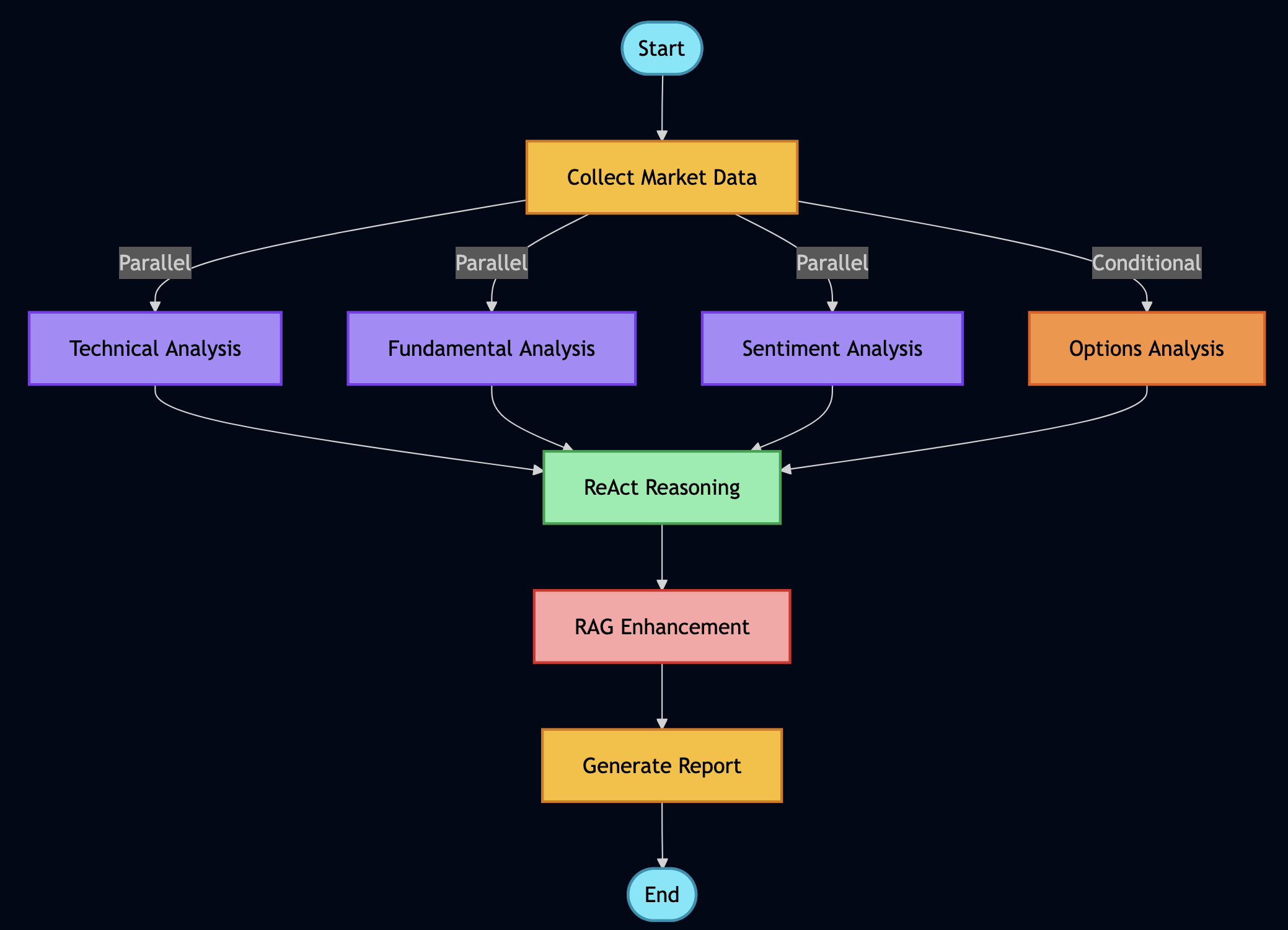

- LangGraph – orchestrate complex multi-agent workflows

- 3-Layer Architecture – building easily extensible systems

Full source code: github.com/bhatti/daily-minutes

Let me walk you through how I built each piece, the problems I encountered, and how I solved them.

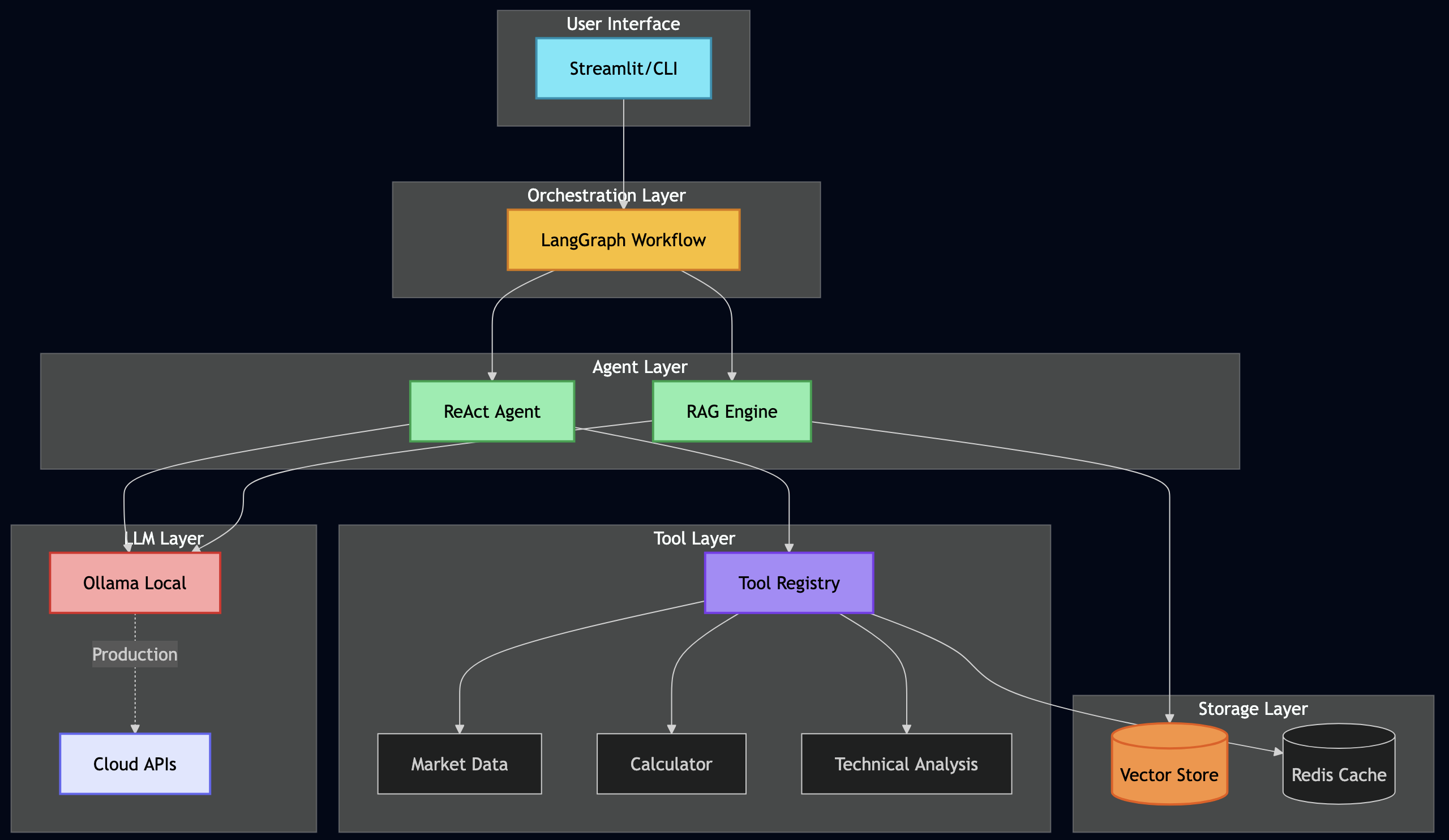

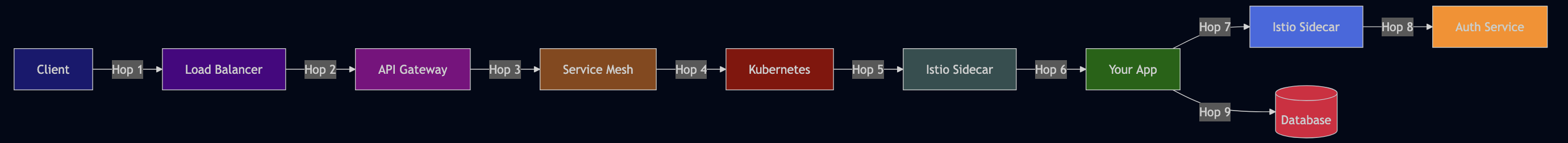

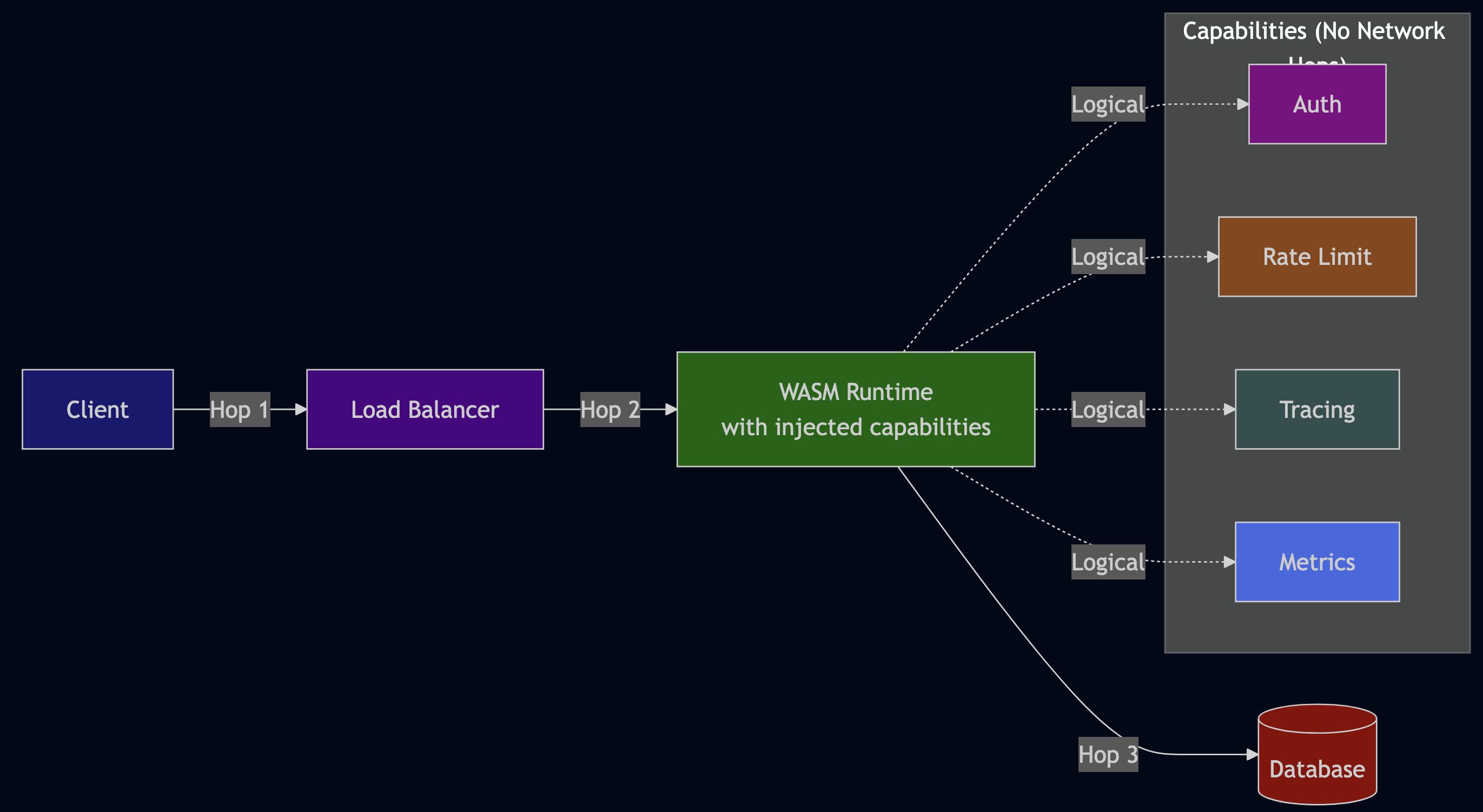

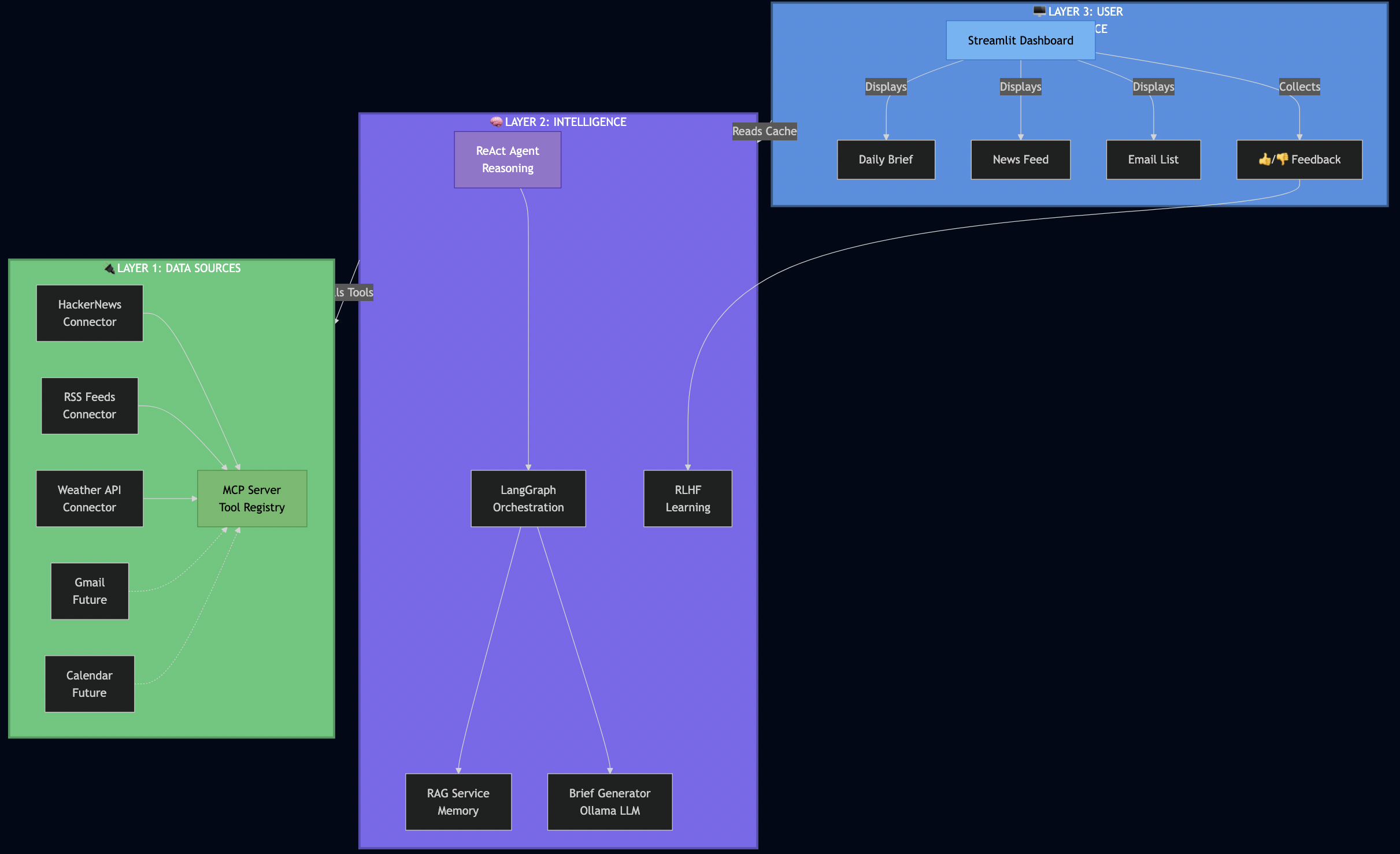

High-level Architecture

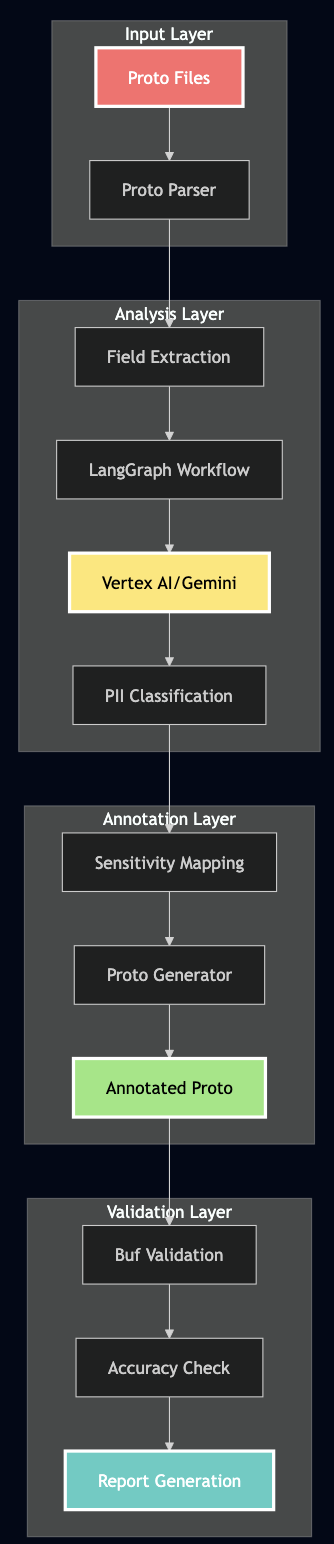

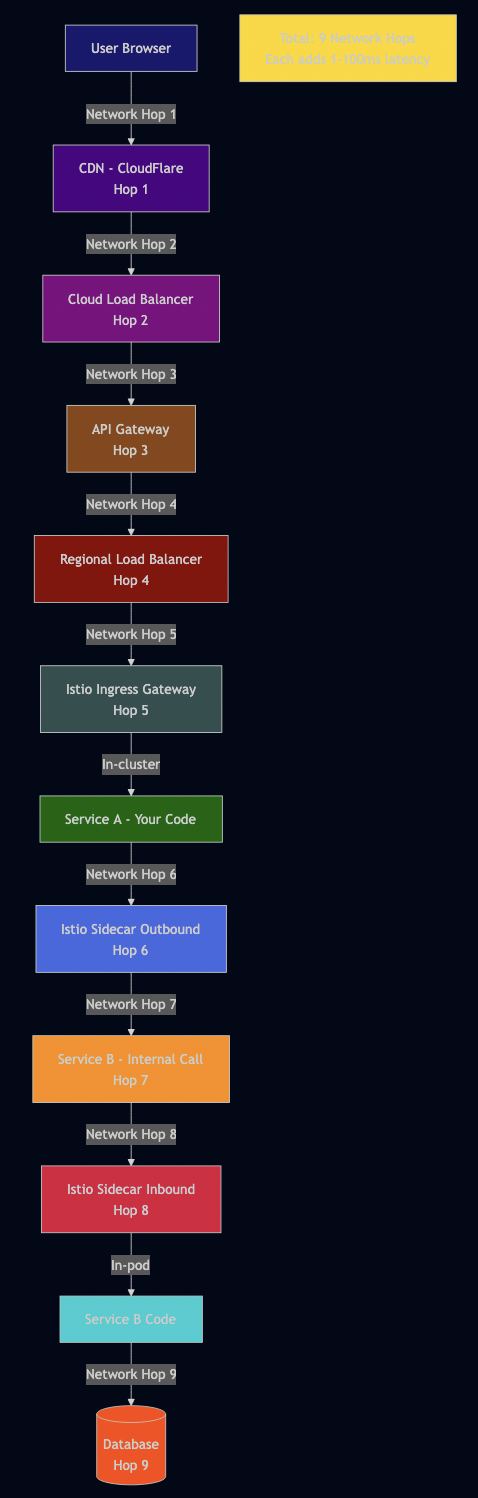

After several iterations, I landed on a clean 3-layer architecture:

Why this architecture worked for me:

Layer 1 (Data Sources) – I used MCP to make connectors pluggable. When I later wanted to add RSS feeds, I just registered a new tool – no changes to the AI logic.

Layer 2 (Intelligence) – This is where the magic happens. The ReAct agent reasons about what data it needs, LangGraph orchestrates fetching from multiple sources in parallel, RAG provides historical context, and RLHF learns from my feedback.

Layer 3 (UI) – I kept the UI simple and fast. It reads from a database cache, so it loads instantly – no waiting for AI to process.

How the Database Cache Works

This is a key architectural decision that made the UI lightning-fast:

# src/services/startup_service.py

async def preload_daily_data():

"""Background job that generates brief and caches in database."""

# 1. Fetch all data in parallel (LangGraph orchestration)

data = await langgraph_orchestrator.fetch_all_sources()

# 2. Generate AI brief (ReAct agent with RAG)

brief = await brief_generator.generate(

emails=data['emails'],

calendar=data['calendar'],

news=data['news'],

weather=data['weather']

)

# 3. Cache everything in SQLite

await db.set_cache('daily_brief_data', brief.to_dict(), ttl=3600) # 1 hour TTL

await db.set_cache('news_data', data['news'], ttl=3600)

await db.set_cache('emails_data', data['emails'], ttl=3600)

logger.info("? All data preloaded and cached")

# src/ui/components/daily_brief.py

def render_daily_brief_section():

"""UI just reads from cache - no AI processing!"""

# Fast read from database (milliseconds, not seconds)

if 'data' in st.session_state and st.session_state.data.get('daily_brief'):

brief_data = st.session_state.data['daily_brief']

_display_persisted_brief(brief_data) # Instant!

else:

st.info("Run `make preload` to generate your first brief.")Why this architecture rocks:

- ? UI loads in <500ms (reading from SQLite cache)

- ? Background refresh (run

make preloador schedule with cron) - ? Persistent (brief survives app restarts)

- ? Testable (can test UI without LLM calls)

Part 1: Setting Up My Local AI Stack

First, I needed to get Ollama running locally. This took me about 30 minutes.

Installing Ollama

# On macOS (what I use) brew install ollama # Start the service ollama serve # Pull the models I chose ollama pull qwen2.5:7b # Main LLM - fast on my M3 Mac ollama pull nomic-embed-text # For RAG embeddings

Why I chose Qwen 2.5 (7B):

- ? Runs fast on my M3 MacBook Pro (no GPU needed)

- ? Good reasoning capabilities for summarization

- ? Small enough to iterate quickly (responses in 2-3 seconds)

- ? Free and private – data never leaves my laptop

Later, I can swap to GPT-4 or Claude with just a config change when I deploy to production.

Testing My Setup

I wanted to make sure Ollama was working before going further:

# Quick test

PYTHONPATH=. python -c "

import asyncio

from src.services.ollama_service import get_ollama_service

async def test():

ollama = get_ollama_service()

result = await ollama.generate('Explain RAG in one sentence.')

print(result)

asyncio.run(test())

"

# Output I got:

# RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) enhances LLM responses by retrieving

# relevant information from a knowledge base before generating answers.? First milestone: Local AI working!

Part 2: Building MCP Connectors

Instead of hard coding data fetching like this:

# ? My first attempt (brittle)

async def get_daily_data():

news = await fetch_hackernews()

weather = await fetch_weather()

# Later I wanted to add RSS feeds... had to modify this function

# Then I wanted Slack... modified again

# This was getting messy fast!I decided to use MCP (Model Context Protocol) to register data sources as “tools” so that the AI can discover and call by name:

Building News Connector

I started with HackerNews since I check it every morning:

# src/connectors/hackernews.py

class HackerNewsConnector:

"""Fetches top stories from HackerNews API."""

async def execute_async(self, max_stories: int = 10):

"""The main method MCP will call."""

# 1. Fetch top story IDs

response = await self.client.get(

"https://hacker-news.firebaseio.com/v0/topstories.json"

)

story_ids = response.json()[:max_stories]

# 2. Fetch each story (I fetch these in parallel for speed)

articles = []

for story_id in story_ids:

story = await self._fetch_story(story_id)

articles.append(self._convert_to_article(story))

return articlesKey learning: Keep connectors simple. They should do ONE thing: fetch data and return it in a standard format.

Registering with MCP Server

Then I registered this connector with my MCP server:

# src/services/mcp_server.py

class MCPServer:

"""The tool registry that AI agents query."""

def _register_tools(self):

# Register HackerNews

self.tools["fetch_hackernews"] = MCPTool(

name="fetch_hackernews",

description="Fetch top tech stories from HackerNews with scores and comments",

parameters={

"max_stories": {

"type": "integer",

"description": "How many stories to fetch (1-30)",

"default": 10

}

},

executor=HackerNewsConnector()

)This allows my AI to discover this tool and call it without me writing any special integration code!

Testing MCP Discovery

# I tested if the AI could discover my tools

PYTHONPATH=. python -c "

from src.services.mcp_server import get_mcp_server

mcp = get_mcp_server()

print('Available tools:')

for tool in mcp.list_tools():

print(f' ? {tool[\"name\"]}: {tool[\"description\"]}')

"

# Output I got:

# Available tools:

# ? fetch_hackernews: Fetch top tech stories from HackerNews...

# ? get_current_weather: Get current weather conditions...

# ? fetch_rss_feeds: Fetch articles from configured RSS feeds...Later, when I wanted to add RSS feeds, I just created a new connector and registered it. The AI automatically discovered it – no changes needed to my ReAct agent or LangGraph workflows!

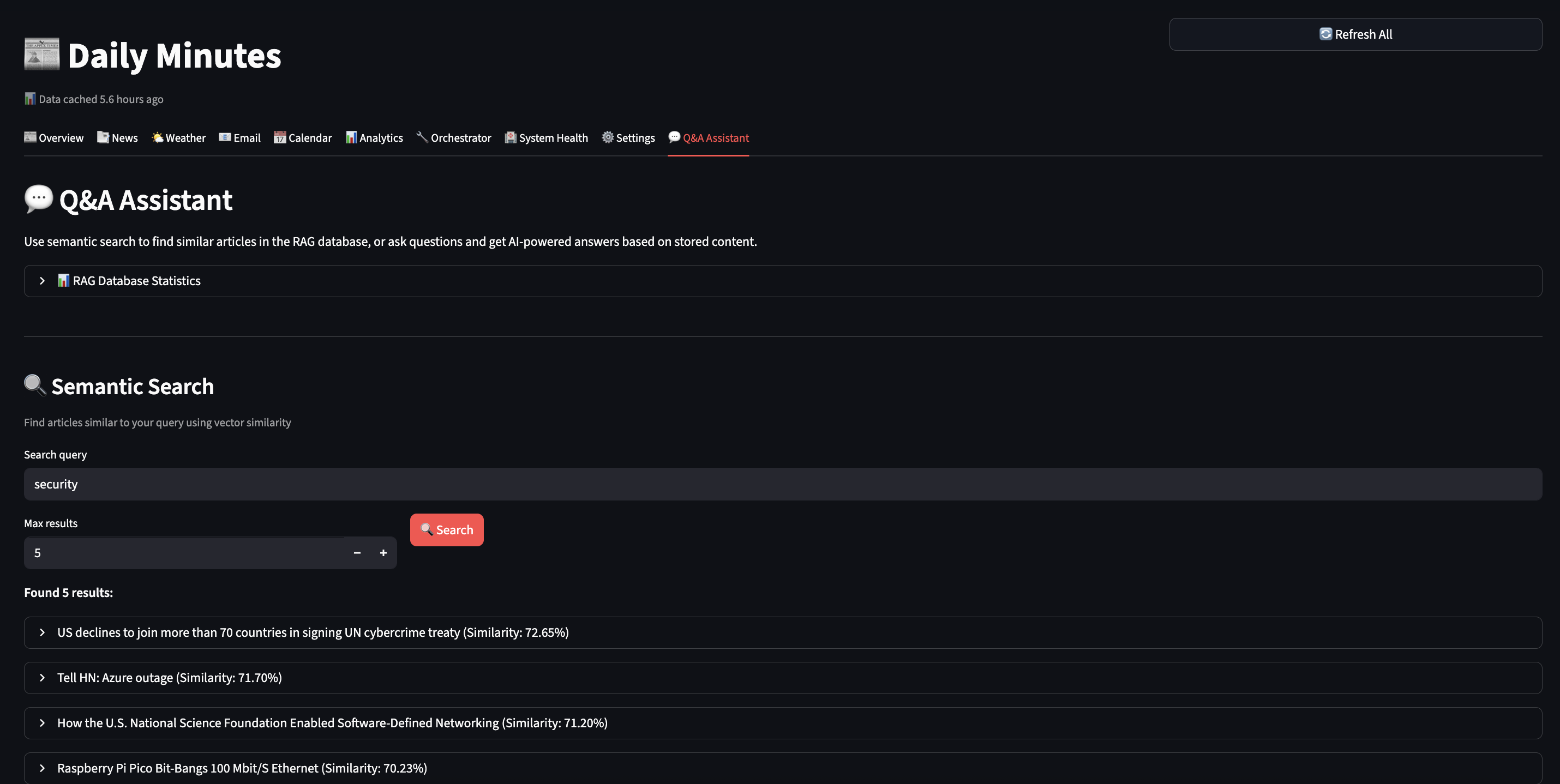

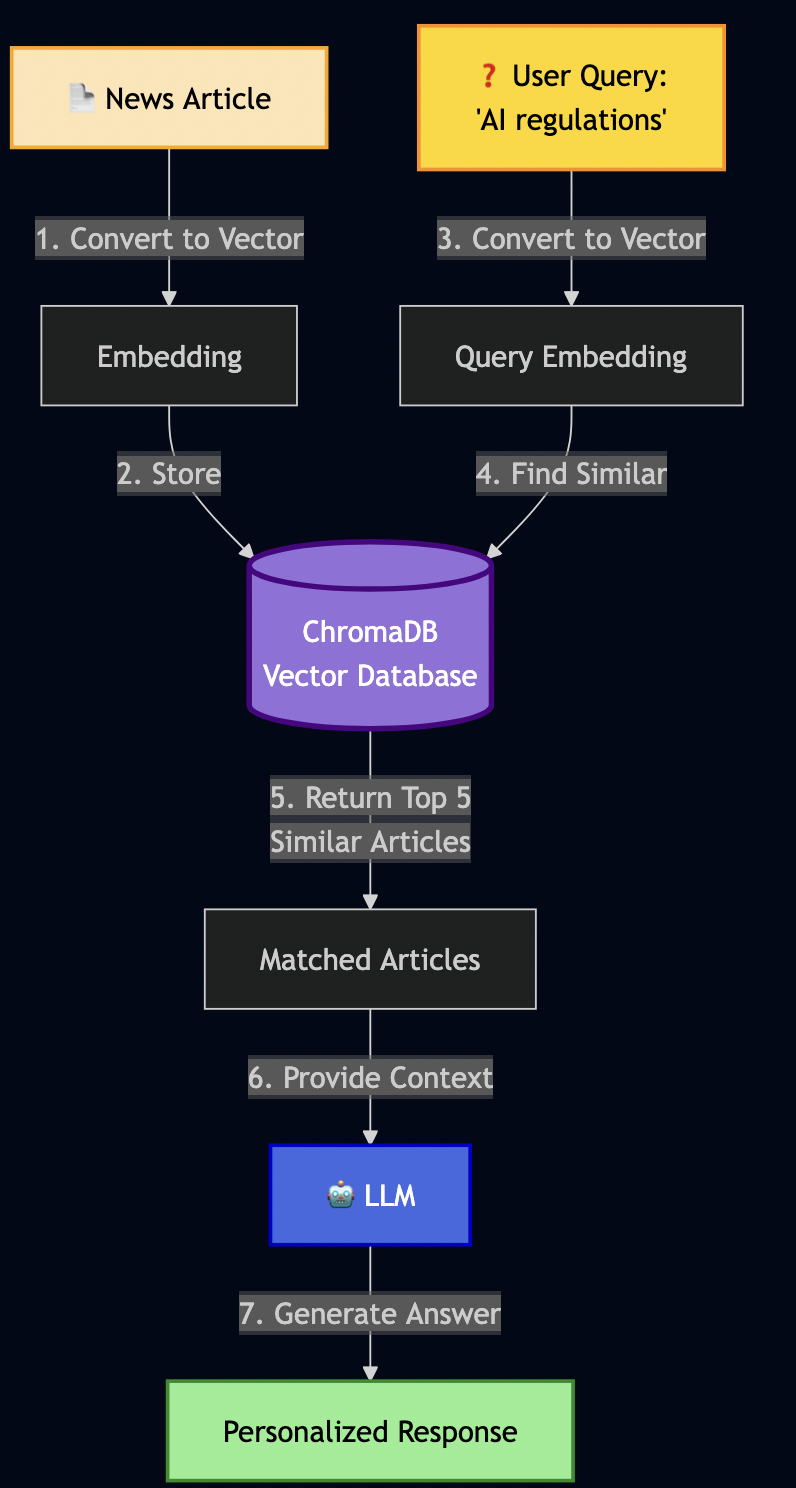

Part 3: Building RAG Pipeline

As LLM have limited context window, RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) can be used to create an AI semantic memory by:

- Converting text to vectors (embeddings)

- Storing vectors in a database (ChromaDB)

- Searching by meaning, not just keywords

Building RAG Service

I then implemented RAG service as follows:

# src/services/rag_service.py

class RAGService:

"""Semantic memory using ChromaDB."""

def __init__(self):

# Initialize ChromaDB (stores on disk)

self.client = chromadb.Client(Settings(

persist_directory="./data/chroma_data"

))

# Create collection for my articles

self.collection = self.client.get_or_create_collection(

name="daily_minutes"

)

# Ollama for creating embeddings

self.ollama = get_ollama_service()

async def add_document(self, content: str, metadata: dict):

"""Store a document with its vector embedding."""

# 1. Convert text to vector (this is the magic!)

embedding = await self.ollama.create_embeddings(content)

# 2. Store in ChromaDB with metadata

self.collection.add(

documents=[content],

embeddings=[embedding],

metadatas=[metadata],

ids=[hashlib.md5(content.encode()).hexdigest()]

)

async def search(self, query: str, max_results: int = 5):

"""Semantic search - find by meaning!"""

# 1. Convert query to vector

query_embedding = await self.ollama.create_embeddings(query)

# 2. Find similar documents (cosine similarity)

results = self.collection.query(

query_embeddings=[query_embedding],

n_results=max_results

)

return resultsI then tested it:

# I stored an article about EU AI regulations

await rag.add_document(

content="European Union announces comprehensive AI safety regulations "

"focusing on transparency, accountability, and privacy protection.",

metadata={"type": "article", "topic": "ai_safety"}

)

# Later, I searched using different words

results = await rag.search("privacy rules for artificial intelligence")This shows that RAG isn’t just storing text – it understands meaning through vector mathematics.

What I Store in RAG

Over time, I started storing other data like emails, todos, events, etc:

# 1. News articles (for historical context)

await rag.add_article(article)

# 2. Action items from emails

await rag.add_todo(

"Complete security training by Nov 15",

source="email",

priority="high"

)

# 3. Meeting context

await rag.add_document(

"Q4 Planning Meeting - need to prepare budget estimates",

metadata={"type": "meeting", "date": "2025-02-01"}

)

# 4. User preferences (this feeds into RLHF later!)

await rag.add_document(

"User marked 'AI safety' topics as important",

metadata={"type": "preference", "category": "ai_safety"}

)With this AI memory, it can answer questions like:

- “What do I need to prepare for tomorrow’s meeting?”

- “What AI safety articles did I read this week?”

- “What are my pending action items?”

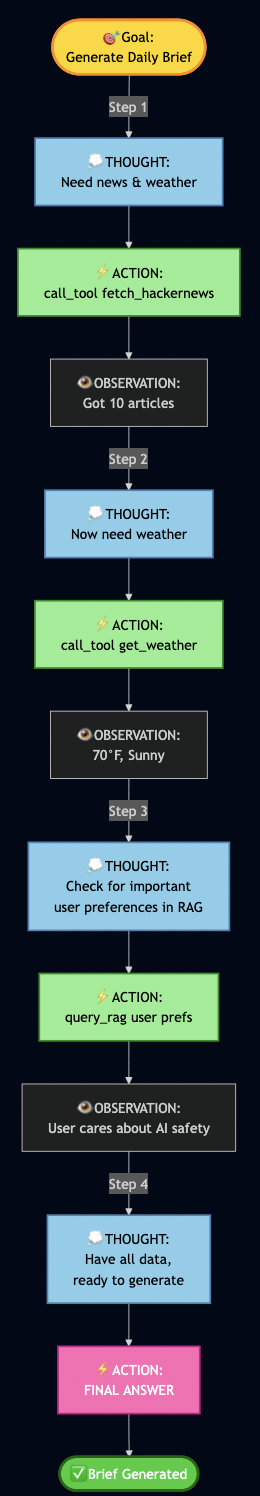

Part 4: Building the ReAct Agent

In my early prototyping, the implementation just executed blindly:

# ? First attempt - no thinking!

async def generate_brief():

news = await fetch_all_news() # Fetches everything

summary = await llm.generate(f"Summarize: {news}")

return summaryThis wasted time fetching data I didn’t need. I wanted my AI to reason first, then act so I applied ReAct (Reasoning + Acting), which works in a loop:

- THOUGHT: AI reasons about what to do next

- ACTION: AI executes a tool/function

- OBSERVATION: AI observes the result

- Repeat until goal achieved

Implementing My ReAct Agent

Here is how it ReAct agent was built:

# src/agents/react_agent.py

class ReActAgent:

"""Agent that thinks before acting."""

async def run(self, goal: str):

"""Execute goal using ReAct loop."""

steps = []

observations = []

for step_num in range(1, self.max_steps + 1):

# 1. THOUGHT: Ask AI what to do next

thought = await self._generate_thought(goal, steps, observations)

# Check if we're done

if "FINAL ANSWER" in thought:

return self._extract_answer(thought)

# 2. ACTION: Parse what action to take

action = self._parse_action(thought)

# Example: {"action": "call_tool", "tool": "fetch_hackernews"}

# 3. EXECUTE: Run the action via MCP

observation = await self._execute_action(action)

observations.append(observation)

# Record this step for debugging

steps.append({

"thought": thought,

"action": action,

"observation": observation

})

return {"steps": steps, "answer": "Max steps reached"}The hardest part was writing the prompts that made the AI reason properly:

async def _generate_thought(self, goal, steps, observations):

"""Generate next reasoning step."""

prompt = f"""Goal: {goal}

Previous steps:

{self._format_steps(steps)}

Available actions:

- query_rag(query): Search my semantic memory

- call_tool(name, params): Execute an MCP tool

- FINAL ANSWER: When you have everything needed

Think step-by-step. What should I do next?

Format your response as:

THOUGHT: <your reasoning>

ACTION: <action to take>

"""

return await self.ollama.generate(prompt, temperature=0.7)I added debug logging to see the AI’s reasoning:

? Goal: Generate my daily brief

Step 1:

? THOUGHT: I need to gather news, check weather, and see user preferences

? ACTION: call_tool("fetch_hackernews", max_stories=10)

?? OBSERVATION: Fetched 10 articles about AI, privacy, and tech

Step 2:

? THOUGHT: Got news. User preferences would help prioritize.

? ACTION: query_rag("user interests and preferences")

?? OBSERVATION: User cares about AI safety, security, privacy

Step 3:

? THOUGHT: Should filter articles to user's interests

? ACTION: call_tool("get_current_weather", location="Seattle")

?? OBSERVATION: 70°F, Partly cloudy

Step 4:

? THOUGHT: I have news (filtered by user interests), weather. Ready to generate.

? ACTION: FINAL ANSWER

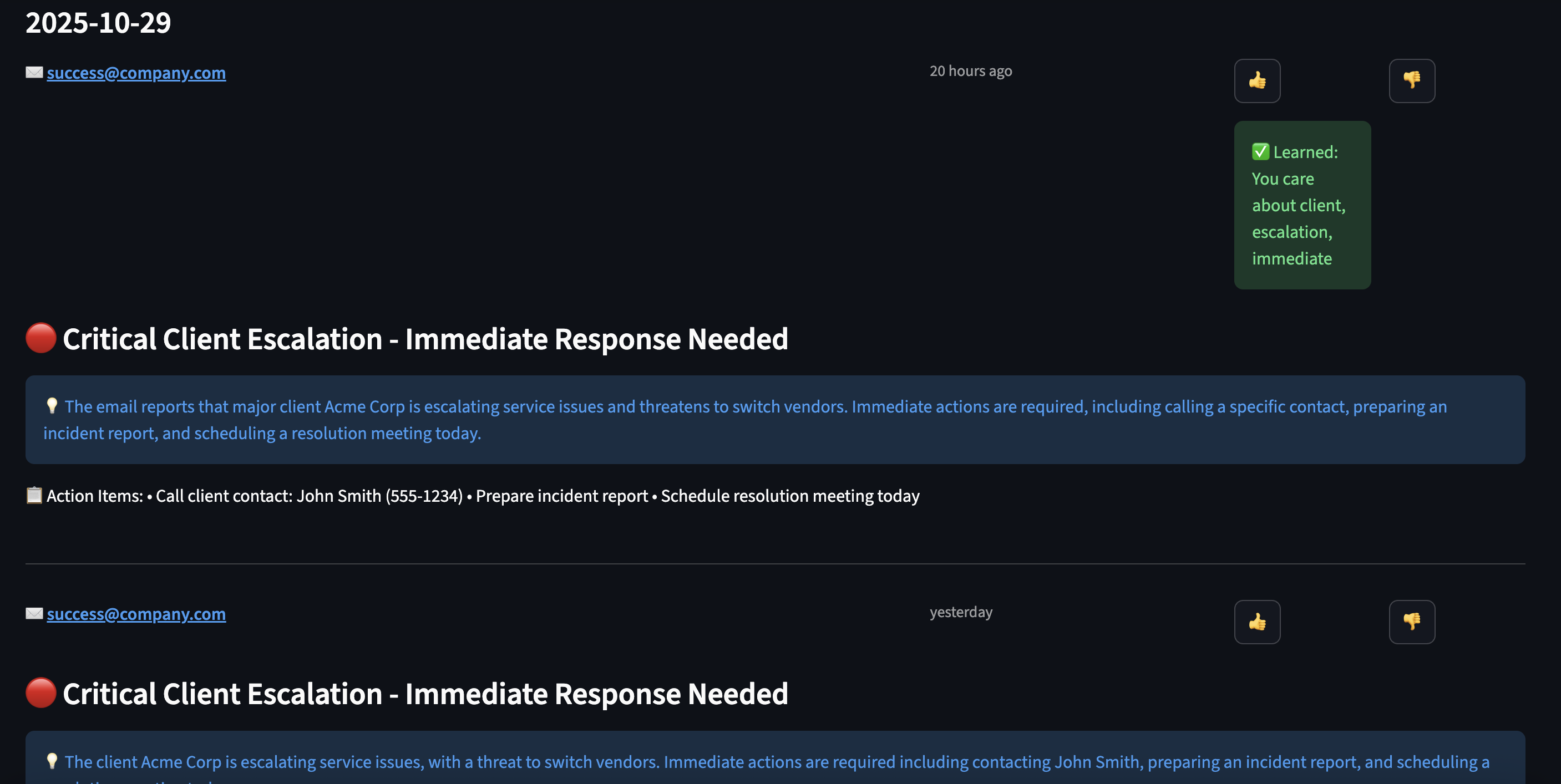

? Generated personalized brief highlighting AI safety articlesPart 5: Adding RLHF

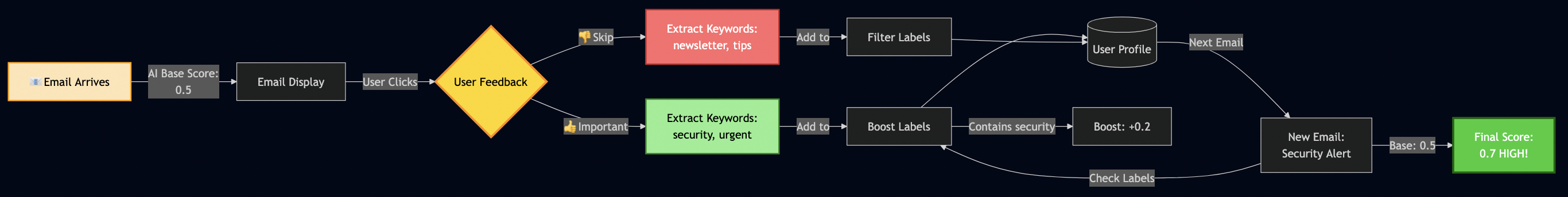

Initially, my AI scored all emails the same way:

? "Newsletter: 10 CSS Tips" ? Importance: 0.5 ? "URGENT: Production outage!" ? Importance: 0.5

So I used RLHF to teach my AI what I care about.

Implementing RLHF Scoring

I added a mixin to my email model:

# src/models/email.py

class ImportanceScoringMixin:

"""Learn from user feedback."""

importance_score: float = 0.5 # AI's base score

boost_labels: Set[str] = set() # Words user marked important

filter_labels: Set[str] = set() # Words user wants to skip

def apply_rlhf_boost(self, content_text: str) -> float:

"""Adjust score based on learned preferences."""

adjusted = self.importance_score

content_lower = content_text.lower()

# Boost if content matches important keywords

for label in self.boost_labels:

if label.lower() in content_lower:

adjusted += 0.1 # Bump up priority!

# Penalize if content matches skip keywords

for label in self.filter_labels:

if label.lower() in content_lower:

adjusted -= 0.2 # Push down priority!

# Keep in valid range [0, 1]

return max(0.0, min(1.0, adjusted))Note: Code examples are simplified for clarity.

See GitHub for the full production implementation.

Adding Feedback UI

In my Streamlit dashboard, I added ?/? buttons:

# User sees an email

for email in emails:

col1, col2, col3 = st.columns([8, 1, 1])

with col1:

st.write(f"**{email.subject}**")

st.info(email.snippet)

with col2:

if st.button("?", key=f"important_{email.id}"):

# Extract what made this important

keywords = await extract_keywords(email.subject + email.body)

# Add to boost labels

user_profile.boost_labels.update(keywords)

st.success(f"? Learned: You care about {', '.join(keywords)}")

with col3:

if st.button("?", key=f"skip_{email.id}"):

# Learn to deprioritize these

keywords = await extract_keywords(email.subject)

user_profile.filter_labels.update(keywords)

st.success(f"? Will deprioritize: {', '.join(keywords)}")Part 6: Orchestrating with LangGraph

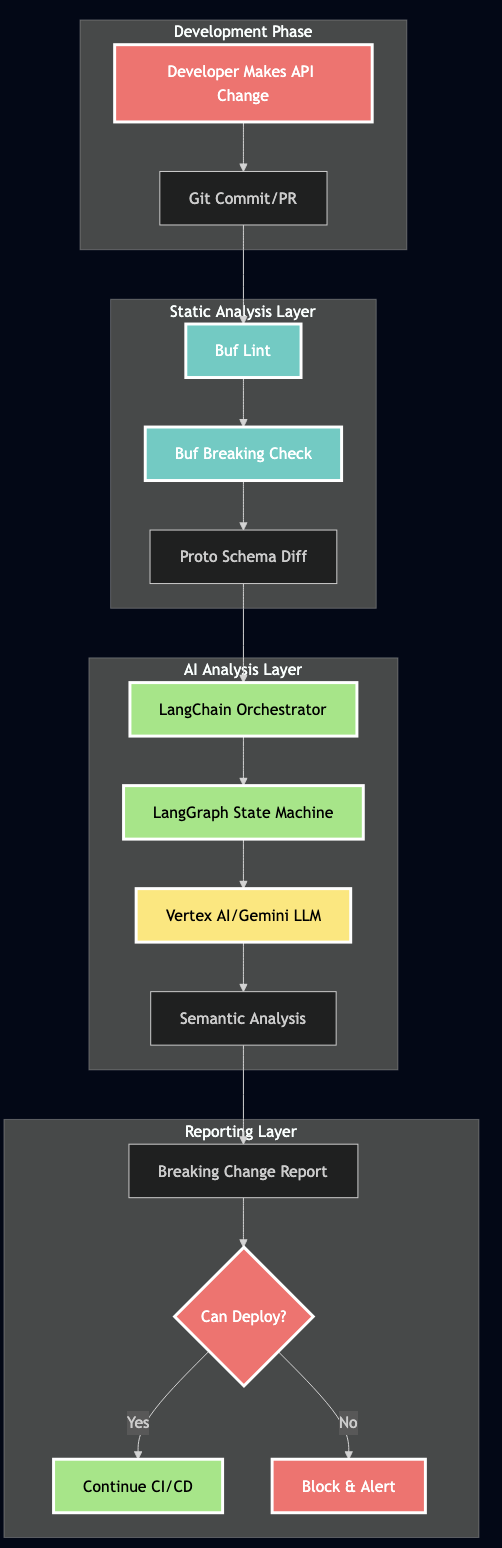

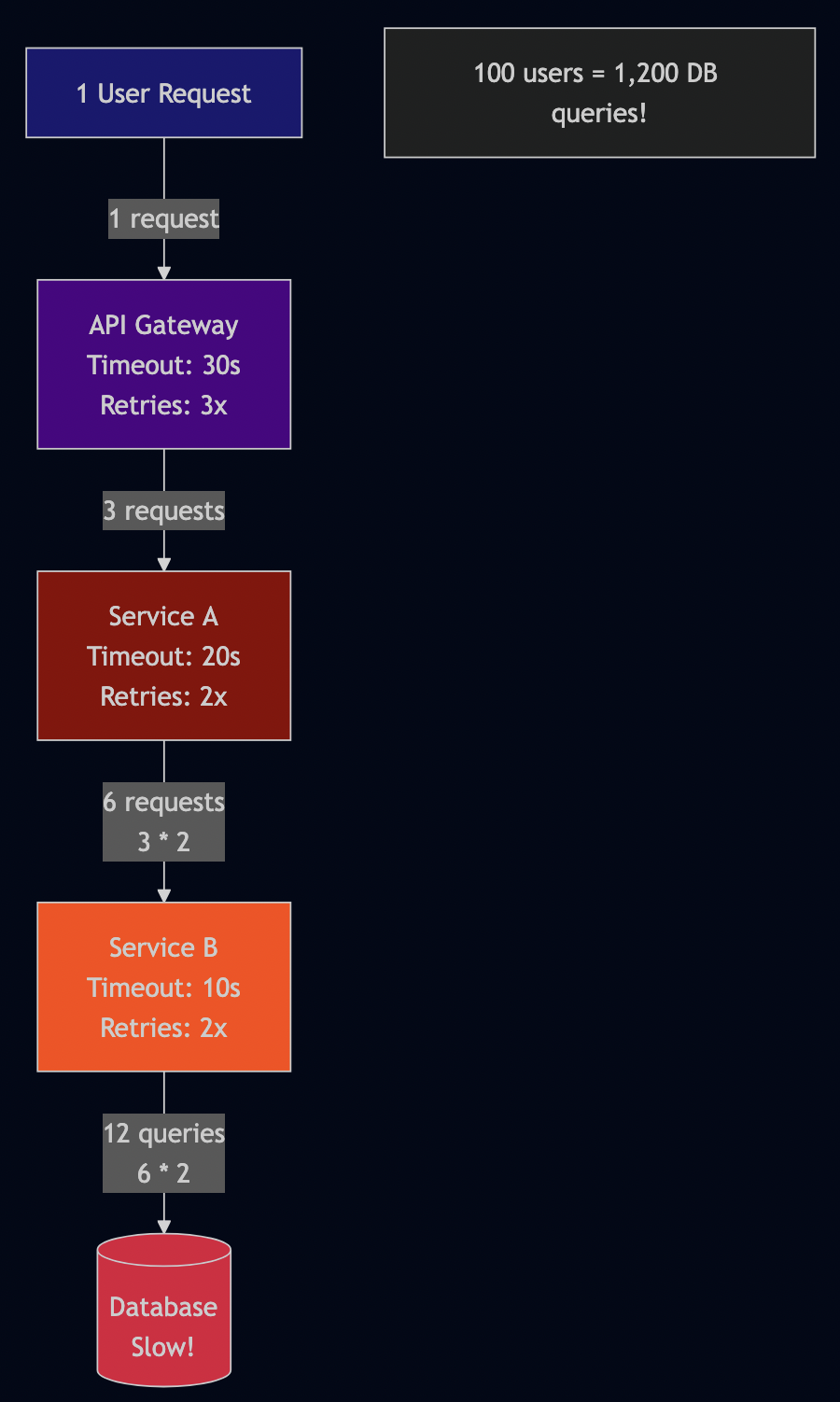

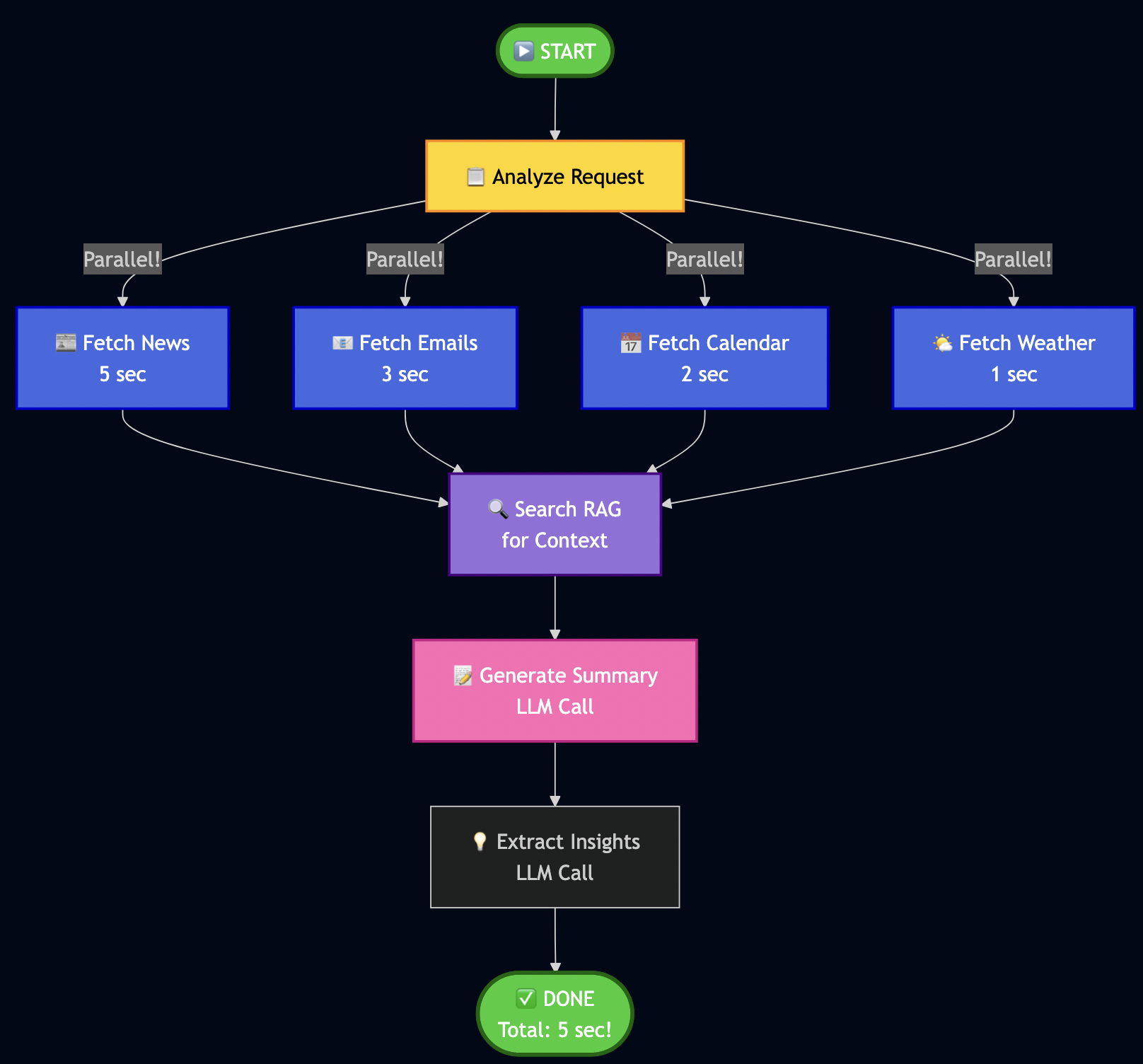

Instead of fetching contents from all data sources sequential for the daily minutes:

# ? Sequential execution - SLOW! news = await fetch_news() # 5 seconds emails = await fetch_emails() # 3 seconds calendar = await fetch_calendar() # 2 seconds weather = await fetch_weather() # 1 second # Total: 11 seconds just waiting! ?

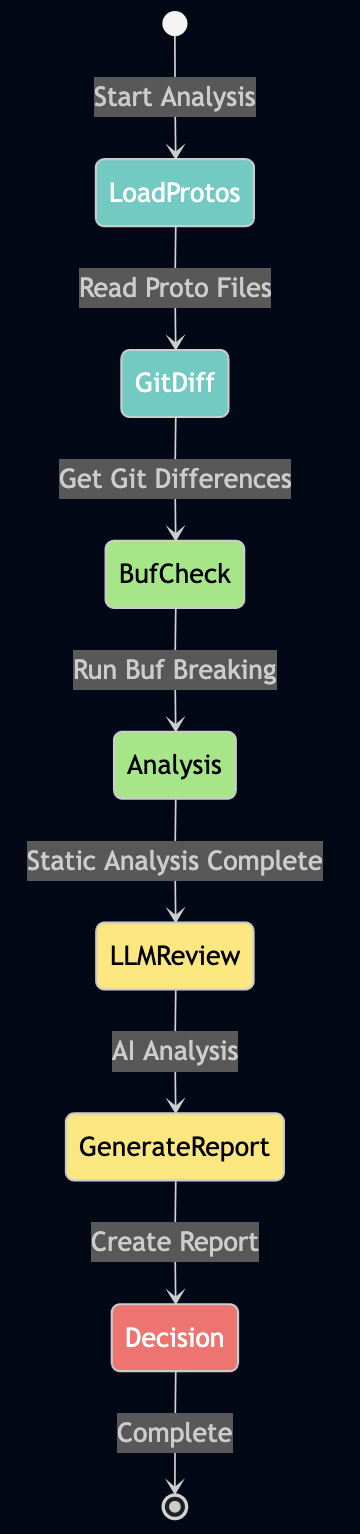

I used LangGraph to define workflows as graphs with parallel execution:

Key insight: Parallel fetch reduced the fetch time for downloading data from various sources.

Building My Workflow

# src/services/langgraph_orchestrator.py

from langgraph.graph import StateGraph, END

class LangGraphOrchestrator:

def _create_workflow(self):

"""Define my workflow graph."""

workflow = StateGraph(WorkflowState)

# Add nodes (processing steps)

workflow.add_node("analyze", self._analyze_request)

workflow.add_node("fetch_news", self._fetch_news)

workflow.add_node("fetch_emails", self._fetch_emails)

workflow.add_node("fetch_calendar", self._fetch_calendar)

workflow.add_node("search_rag", self._search_context)

workflow.add_node("generate_summary", self._generate_summary)

# Define edges (execution flow)

workflow.set_entry_point("analyze")

# Parallel fetch (all happen at once!)

workflow.add_edge("analyze", "fetch_news")

workflow.add_edge("analyze", "fetch_emails")

workflow.add_edge("analyze", "fetch_calendar")

# All converge to RAG search

workflow.add_edge("fetch_news", "search_rag")

workflow.add_edge("fetch_emails", "search_rag")

workflow.add_edge("fetch_calendar", "search_rag")

# Sequential processing

workflow.add_edge("search_rag", "generate_summary")

workflow.add_edge("generate_summary", END)

return workflow.compile()Note: WorkflowState is a shared dictionary that nodes pass data through – like a clipboard for the workflow. The analyze node parses the user’s request and decides which data sources are needed.

Implementing Node Functions

Each node is just an async function:

async def _fetch_news(self, state: WorkflowState):

"""Fetch news in parallel."""

try:

articles = await self.mcp.execute_tool(

"fetch_hackernews",

{"max_stories": 10}

)

state["news_articles"] = articles

except Exception as e:

state["errors"].append(f"News fetch failed: {e}")

state["news_articles"] = []

return state

async def _search_context(self, state: WorkflowState):

"""Search RAG for relevant context."""

query = state["user_request"]

results = await self.rag.search(query, max_results=5)

# Build context string

context = "\n".join([r['content'] for r in results])

state["context"] = context

return stateRunning the Workflow

# Execute the complete workflow

result = await orchestrator.run("Generate my daily brief")

# I get back:

{

"news_articles": [...], # 10 articles

"emails": [...], # 5 unread

"calendar_events": [...], # 3 events today

"context": "...", # RAG context

"summary": "...", # Generated brief

"processing_time": 5.2 # Seconds (not 11!)

}The LLM Factory Pattern – How I Made It Cloud-Ready

Following code snippet shows how does the system seamlessly switch between local Ollama and cloud providers:

# src/services/llm_factory.py

def get_llm_service():

"""Factory pattern - works with any LLM provider."""

provider = os.getenv("LLM_PROVIDER", "ollama")

if provider == "ollama":

return OllamaService(

base_url=os.getenv("OLLAMA_BASE_URL", "http://localhost:11434"),

model=os.getenv("OLLAMA_MODEL", "qwen2.5:7b")

)

elif provider == "openai":

return OpenAIService(

api_key=os.getenv("OPENAI_API_KEY"),

model=os.getenv("OPENAI_MODEL", "gpt-4-turbo")

)

elif provider == "google":

# Like in my previous Vertex AI article!

return VertexAIService(

project_id=os.getenv("GCP_PROJECT_ID"),

model="gemini-1.5-flash"

)

raise ValueError(f"Unknown provider: {provider}")

# All services implement the same interface:

class BaseLLMService:

async def generate(self, prompt: str, **kwargs) -> str:

"""Generate text from prompt."""

raise NotImplementedError

async def create_embeddings(self, text: str) -> List[float]:

"""Create vector embeddings."""

raise NotImplementedErrorThe ReAct agent, RAG service, and Brief Generator all use get_llm_service() – they don’t care which provider is running!

Part 7: The Challenges I Faced

Building this system wasn’t smooth. Here are the biggest challenges:

Challenge 1: LLM Generating Vague Summaries

Problem: My early briefs were terrible:

? "Today's news features a mix of technology updates and various topics."

This was useless! I needed specifics.

Solution: I rewrote my prompts with explicit rules:

# ? Better prompt with strict rules

prompt = f"""Generate a daily brief following these STRICT rules:

PRIORITY ORDER (most important first):

1. Urgent emails or action items

2. Today's calendar events

3. Market/business news

4. Tech news

TLDR FORMAT (exactly 3 bullets, be SPECIFIC):

* Bullet 1: Most urgent email/action (include WHO, WHAT, WHEN)

Example: "Client escalation from Acme Corp affecting 50K users - response needed by 2pm"

* Bullet 2: Most important calendar event today (include TIME and WHAT TO PREPARE)

Example: "2pm: Board meeting - prepare Q4 revenue slides"

* Bullet 3: Top market/business news (include NUMBERS/SPECIFICS)

Example: "Federal Reserve raises rates 0.5% to 5.25% - affects tech hiring"

AVOID THESE PHRASES (they're too vague):

? "mix of updates"

? "various topics"

? "continues to make progress"

? "interesting developments"

USE SPECIFIC DETAILS:

? Names (people, companies)

? Numbers (percentages, dollar amounts, deadlines)

? Times (when something happened or needs to happen)

Content to summarize:

{content}

Generate: TLDR (3 bullets), Summary (5-6 detailed sentences), Key Insights (5 bullets)

"""Result: Went from vague ? specific, actionable briefs!

Challenge 2: TLDR Bullets Rendering on Same Line

Problem: My UI showed bullets in one paragraph:

? • Critical email... • Meeting at 2pm... • Market news...

Root cause: Streamlit’s st.info() doesn’t preserve newlines.

Solution: Split and render each bullet separately:

# ? Doesn't work

st.info(tldr)

# ? Works!

tldr_lines = [line.strip() for line in tldr.split('\n') if line.strip()]

for bullet in tldr_lines:

st.markdown(bullet)Challenge 3: AI Prioritizing News Over Personal Tasks

Problem: My brief focused on tech news, ignored my urgent emails:

? TLDR bullet 1: "OpenAI releases GPT-5" (who cares?) TLDR bullet 2: "Crypto market surges" (not relevant to me) TLDR bullet 3: "Client escalation requires response" (BURIED!)

Solution: I restructured my prompt to explicitly label priority:

# src/services/brief_scheduler.py

async def _generate_daily_brief(emails, calendar, news, weather):

"""Generate prioritized daily brief with structured prompt."""

# Separate market vs tech news (market is higher priority)

market_news = [n for n in news if 'market' in n.tags]

tech_news = [n for n in news if 'market' not in n.tags]

# Sort emails by RLHF-boosted importance score

important_emails = sorted(

emails,

key=lambda e: e.apply_rlhf_boost(e.subject + e.snippet),

reverse=True

)[:5] # Top 5 only

# Build structured prompt with clear priority

prompt = f"""

**SECTION 1: IMPORTANT EMAILS (HIGHEST PRIORITY - use for TLDR bullet #1)**

{format_emails(important_emails)}

**SECTION 2: TODAY'S CALENDAR (SECOND PRIORITY - use for TLDR bullet #2)**

{format_calendar(calendar)}

**SECTION 3: MARKET NEWS (THIRD PRIORITY - use for TLDR bullet #3)**

{format_market_news(market_news)}

**SECTION 4: TECH NEWS (LOWEST PRIORITY - summarize briefly)**

{format_tech_news(tech_news)}

**SECTION 5: WEATHER**

{format_weather(weather)}

Generate a daily brief following this EXACT priority order:

1. Email action items FIRST

2. Calendar events SECOND

3. Market/business news THIRD

4. Tech news LAST (brief mention only)

TLDR must have EXACTLY 3 bullets using content from sections 1, 2, 3 (not section 4).

"""

return await llm.generate(prompt)Result: My urgent email moved to bullet #1 where it belongs! The AI now respects the priority structure.

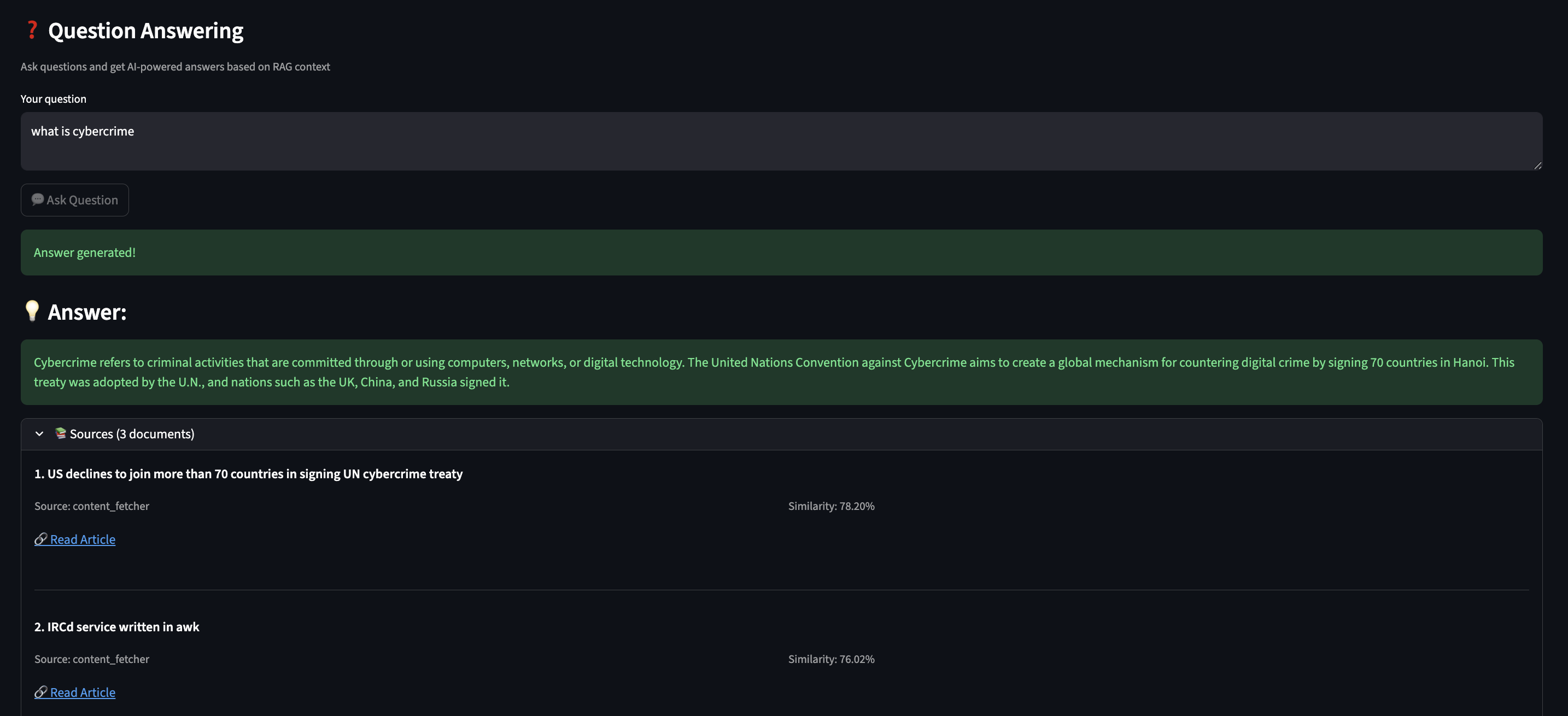

Challenge 4: RAG Returning Irrelevant Results

Problem: Semantic search sometimes returned weird matches:

Query: "AI safety regulations" Result: Article about "safe AI models for healthcare" (wrong context!)

Solution: I added metadata filtering and better embeddings:

# Store with rich metadata

await rag.add_document(

content=article.title,

metadata={

"type": "article",

"category": "ai_safety", # For filtering!

"tags": ["regulation", "eu", "policy"],

"date": "2025-01-28",

"importance": "high"

}

)

# Search with filters

results = await rag.search(

"AI regulations",

filter_metadata={

"category": "ai_safety",

"importance": "high"

}

)Result: Much more relevant results!

Challenge 5: Handling API Failures

Problem: MCP connectors may fail to fetch data from underlying data source.

Solution: I used graceful degradation where brief is generated with available data and error messages/last-updated is marked for failed sources)

Part 8: Future Improvements

This work is by no means done but I am sharing a proof of concept that I have built so far. Here is what still needs work:

Current Limitations

1. Email/Calendar Improvements

- ? Have: I have basic OAuth support for emails and calendar events and mock testing

- ? Missing: Solid OAuth support for Gmail and Google Calendar integration

2. RLHF Needs More Sophisticated Learning

- ? Have: Current system allows simple keyword matching (if email contains “security” ? boost)

- ? Missing: Context-aware learning (distinguish “security update” vs “security breach”)

- Improvement Needed:

# Current: Simple keyword match

if "security" in email:

score += 0.1

# Better: Contextual understanding

if embeddings_similar(email, user.important_emails):

score += contextual_boost # Uses semantic similarity!3. ReAct Agent Sometimes Over-Thinks

- ? Have: AI reasons before acting

- ? Problem: Sometimes takes 4-5 steps when 2 would suffice

- Fix Needed: Better stopping criteria in prompts

4. No Multi-User Support (Yet)

- ? Have: Works great for me

- ? Missing: Can’t handle multiple users with different preferences

- Future: Add user profiles, tenant isolation

5. Brief Generation Can Be Slow (30-60 seconds)

- ? Have: Parallel data fetching (fast)

- ? Bottleneck: LLM generation with Qwen 2.5 on CPU

- Options:

- Use smaller model (faster but less capable)

- Deploy to cloud with faster GPT-4

6. Missing Data Sources

- ? Have: Basic data for news, email and calendar

- ? Slack Integration: Add Slack to monitor important channels and surface urgent threads in daily brief

- ? Social Media Integration: Add social media feed to monitor trending topics or news

Part 9: How to Extend This System

I designed this to be easily extensible. Here’s how you can add new features:

Adding a New Data Source (Example: Slack)

Step 1: Create the connector

# src/connectors/slack.py

class SlackConnector:

"""Fetch recent messages from Slack channels."""

async def execute_async(self, channel: str, max_messages: int = 10):

# 1. Connect to Slack API

client = WebClient(token=os.getenv("SLACK_BOT_TOKEN"))

# 2. Fetch recent messages

response = await client.conversations_history(

channel=channel,

limit=max_messages

)

# 3. Convert to standard format

messages = []

for msg in response['messages']:

messages.append(SlackMessage(

text=msg['text'],

user=msg['user'],

channel=channel,

timestamp=msg['ts']

))

return messagesStep 2: Register with MCP (automatic discovery!)

# src/services/mcp_server.py

def _register_tools(self):

# ... existing tools ...

# Add Slack

self.tools["get_slack_messages"] = MCPTool(

name="get_slack_messages",

description="Fetch recent Slack messages from a channel",

parameters={

"channel": {"type": "string", "description": "Channel name"},

"max_messages": {"type": "integer", "default": 10}

},

executor=SlackConnector()

)Step 3: AI automatically discovers it!

# Your ReAct agent will now see: # "Available tools: fetch_hackernews, get_slack_messages, ..." # No changes needed to ReAct logic!

Step 4: Update brief prompt to include Slack

# src/services/brief_scheduler.py

prompt = f"""

**IMPORTANT EMAILS**: {emails}

**CALENDAR**: {calendar}

**SLACK HIGHLIGHTS**: {slack_messages} # New!

**NEWS**: {news}

Generate brief prioritizing: Email > Calendar > Slack > News

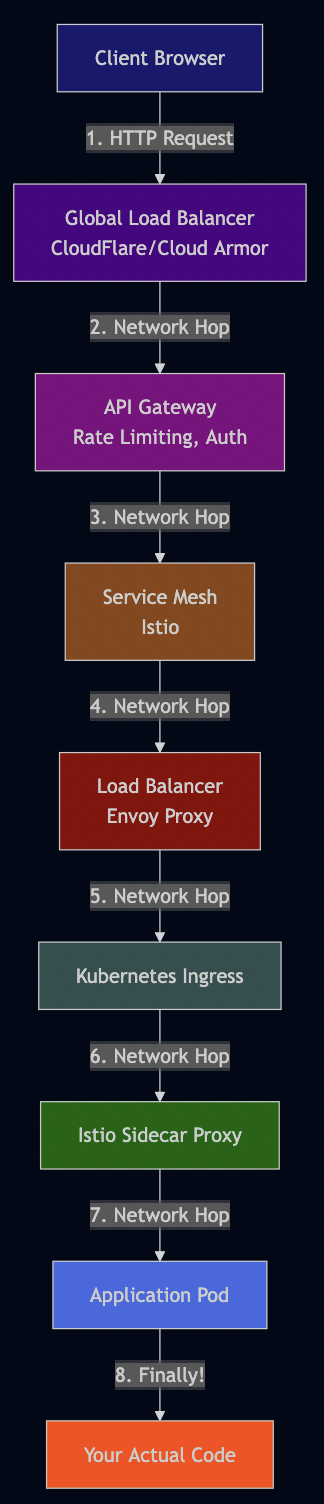

"""Part 10: Local Development vs Cloud

One of my favorite aspects of this architecture: develop locally, deploy to cloud with 1 config change.

Development (What I Use Daily)

# .env.development LLM_PROVIDER=ollama LLM_OLLAMA_BASE_URL=http://localhost:11434 LLM_OLLAMA_MODEL=qwen2.5:7b DATABASE_URL=sqlite:///./data/daily_minutes.db REDIS_URL=redis://localhost:6379

Benefits I experience daily:

- ? Free: Zero API costs (I iterate 50+ times/day)

- ? Fast: No network latency, responses in 2-3 seconds

- ? Private: My emails never touch the internet

- ? Offline: Works on planes, cafes without WiFi

Trade-offs I accept:

- ?? Slower than GPT-4

- ?? Less capable reasoning (7B vs 175B+ parameters)

- ?? Manual updates (pull new Ollama models myself)

Production

# .env.production LLM_PROVIDER=openai # Just change this line! OPENAI_API_KEY=sk-... OPENAI_MODEL=gpt-4-turbo DATABASE_URL=postgresql://... # Scalable DB REDIS_URL=redis://prod-cluster:6379 # Distributed cache

The magic: Same code, different LLM!

# src/services/llm_factory.py

def get_llm_service():

"""Factory pattern - works with any LLM."""

provider = os.getenv("LLM_PROVIDER", "ollama")

if provider == "ollama":

return OllamaService()

elif provider == "openai":

return OpenAIService()

elif provider == "anthropic":

return ClaudeService()

elif provider == "google":

return VertexAIService() # Like in my previous article!

raise ValueError(f"Unknown provider: {provider}")Part 11: Testing Everything

I used TDD extensively to build each feature so that it’s easy to debug if something is not working:

Unit Tests

# Test MCP tool registration pytest tests/unit/test_mcp_server.py -v # Test RAG semantic search pytest tests/unit/test_rag_service.py -v # Test ReAct reasoning pytest tests/unit/test_react_agent.py -v # Test RLHF scoring pytest tests/unit/test_rlhf_scoring.py -v # Run all unit tests pytest tests/unit/ -v # 516 passed in 45.23s ?

Integration Tests

Also, in some cases unit tests couldn’t fully validate so I wrote integration tests to test persistence logic with sqlite database or generating real analysis from news:

# tests/integration/test_brief_quality.py

async def test_tldr_has_three_bullets():

"""TLDR must have exactly 3 bullets."""

brief = await db.get_cache('daily_brief_data')

tldr = brief.get('tldr', '')

bullets = [line for line in tldr.split('\n') if line.strip().startswith('•')]

assert len(bullets) == 3, f"Expected 3 bullets, got {len(bullets)}"

assert "email" in bullets[0].lower() or "urgent" in bullets[0].lower()

assert "calendar" in bullets[1].lower() or "meeting" in bullets[1].lower()

async def test_no_generic_phrases():

"""Brief should not contain vague phrases."""

brief = await db.get_cache('daily_brief_data')

summary = brief.get('summary', '')

bad_phrases = ["mix of updates", "various topics", "continues to"]

for phrase in bad_phrases:

assert phrase not in summary.lower(), f"Found generic phrase: {phrase}"Manual Testing (My Daily Workflow)

# 1. Fetch data and generate brief make preload # Output I see: # ? Fetching news from HackerNews... (10 articles) # ? Fetching weather... (70°F, Sunny) # ? Analyzing articles with AI... (15 articles) # ? Generating daily brief... (Done in 18.3s) # ? Brief saved to database # 2. Launch UI streamlit run src/ui/streamlit_app.py # 3. Check brief quality # - Is TLDR specific? (not vague) # - Are priorities correct? (email > calendar > news) # - Are action items extracted? (from emails) # - Did RLHF work? (boosted my preferences)

Note: You can schedule preload via cron, e.g., I run it at 6am daily so that brief is ready when I wake up.

Conclusion

Building this Daily Minutes assistant changed how I start my day by giving me a personalized 3-minute brief highlighting what truly matters. Agentic AI excels at automating complex workflows that require judgment, not just execution. The ReAct agent reasons through prioritization. RAG provides contextual memory across weeks of interactions. RLHF learns from my feedback, getting smarter about what I care about. LangGraph orchestrates parallel execution across multiple data sources. These building blocks work together to handle decisions that traditionally needed human attention.

I’m sharing this as a proof of concept, not a finished product. The code works, saves me real time, and demonstrates these techniques effectively. But I’m still iterating. The OAuth integration and error handling needs improvements. The RLHF scoring could be more sophisticated. The ReAct agent sometimes overthinks simple tasks. I’m adding these improvements gradually, testing each change against my daily routine.

The real lesson? Start small, validate with real use, then scale with confidence. I used Claude Code to build this in spare time over a couple weeks. You can do the same—clone the repo, adapt it to your workflow, and see where agentic AI saves you time.

Try It Yourself

# Clone my repo git clone https://github.com/bhatti/daily-minutes cd daily-minutes # Install dependencies pip install -r requirements.txt # Setup Ollama ollama pull qwen2.5:7b ollama pull nomic-embed-text # Generate your first brief make preload # Launch dashboard streamlit run src/ui/streamlit_app.py