I recently read “The Engineering Executive’s Primer“, a comprehensive guide for helping engineering leaders navigate challenges like strategic planning, effective communication, hiring, and more. Here are the key highlights from the book, organized by chapter:

1. Getting the Job

This chapter focuses on securing an executive role and successfully navigating the executive interview process.

Why Pursue an Executive Role?

The author suggests reflecting on this question personally and then reviewing your thoughts with a few peers or mentors to gather feedback.

One of One

While there are general guidelines for searching an executive role, each executive position and the process are unique and singular.

Finding Internal Executive Roles

Finding an executive role internally can be challenging, as companies often look for executives with skill sets that differ from those currently in place and peers may feel slighted for not getting the role.

Finding External Executive Roles

The author advises leveraging your established network to find roles before turning to executive recruiters, as many highly respected executive positions often never make it to recruiting firms or public job postings.

Interview Process

The interview process for executive roles is generally a bit chaotic and the author recommends STAR method to keep answers concise and organized. Other advice includes:

- Ask an interviewer for feedback on your presentation before the session.

- Ask what other candidates have done that was particularly well received.

- Make sure to follow the prompt directly.

- Prioritize where you want to spend time in the presentation.

- Leave time for questions.

Negotiating the Contract

The aspects of negotiation include:

- Equity

- Equity acceleration

- Severance package

- Bonus

- Parental leave

- Start date

- Support

Deciding to Take the Job

The author recommends following steps before finalizing your decision:

- Spend enough time with the CEO

- Speak to at least one member of the board

- Speak with members of the executive team

- Speak with finance team to walk through the recent P&L statement

- Make sure they answered your questions

- Reasons of previous executive departure

2. Your First 90 Days

This chapter emphasizes the importance of prioritizing learning, building trust, and gaining a deep understanding of the organization’s health, technology, processes, and overall operations.

What to Lean First?

The author offers following priorities as a starting place:

- How does the business work?

- What defines the culture and its values? How recent key decisions were made?

- How can you establish healthy relationships with peers and stakeholders?

- Is the Engineering team executing effectively on the right work?

- Is technical quality high?

- Is it a high-morale, inclusive engineering team?

- Is the place sustainable for the long haul?

Making the Right System Changes

Senior leaders must understand the systems first and then make durable improvements towards organization goals by making right changes. The author cautions against judging without context and reminiscing about past employers.

You Only Learn When You Reflect

The author recommends learning well through reflection and ask for help using 20-40 rule (spend at least 20-minutes but no more than 40-minutes before asking for help).

Tasks for Your First 90 Days

- Learning and building trust

- Ask your manager to write their explicit expectations for you

- Figure out if something is really wrong and needs immediate attention

- Go on a listening tour

- Set up recurring 1:1s and skip-level meetings

- Share what you’re observing

- Attend routine forums

- Shadow support tickets

- Shadow customer/partner meetings

- Find business analytics and learn to query the data

Create an External Support System

The author recommends building a network of support of folks in similar roles, getting an executive coach and creating a space for self-care.

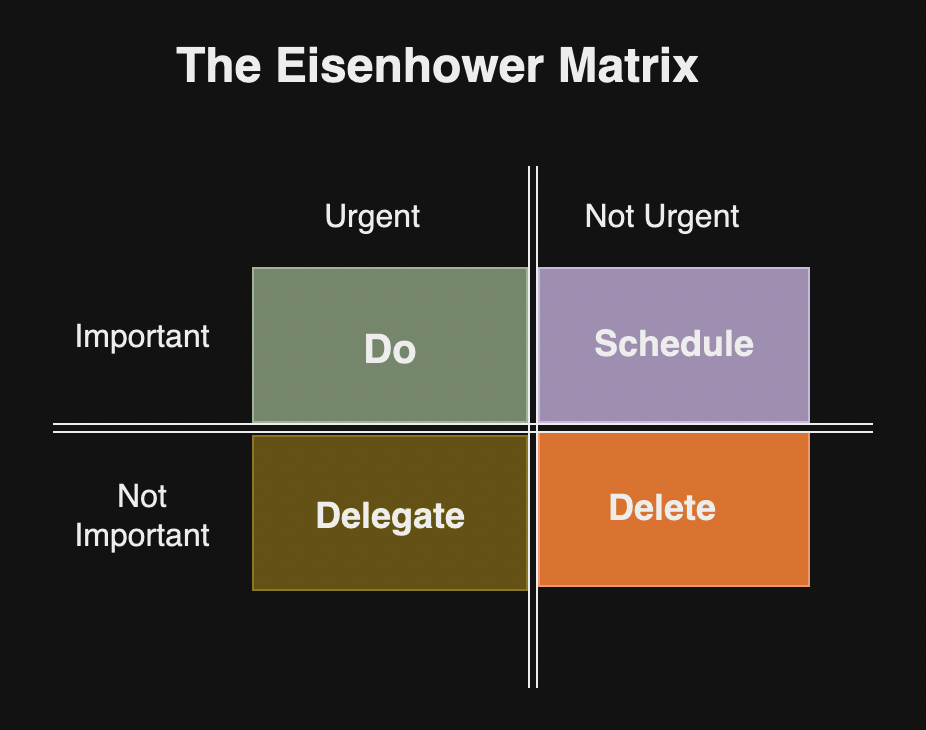

Managing Time and Energy

Understanding organization Health and Process

- Document existing organizational processes

- Implement at most one or two changes

- Plan organizational growth for next year

- Set up communication pathways

- Pay attention beyond the product engineering roles within your organization

- Spot check organizational inclusion

Understanding Hiring

- Track funnel metrics and hiring pipelines

- Shadow existing interviews, onboarding and closing calls

- Decide whether an overhaul is ncessary

- Identify three or fewer key missing roles

- Offer to close priority candidates

- Kick off Engineering brand efforts

Understanding Systems of Execution

- Figure out whether what’s happening now is working and scales

- Establish internal measures of Engineering velocity

- Establish external measures of Engineering velocity

- Consider small changes to process and controls

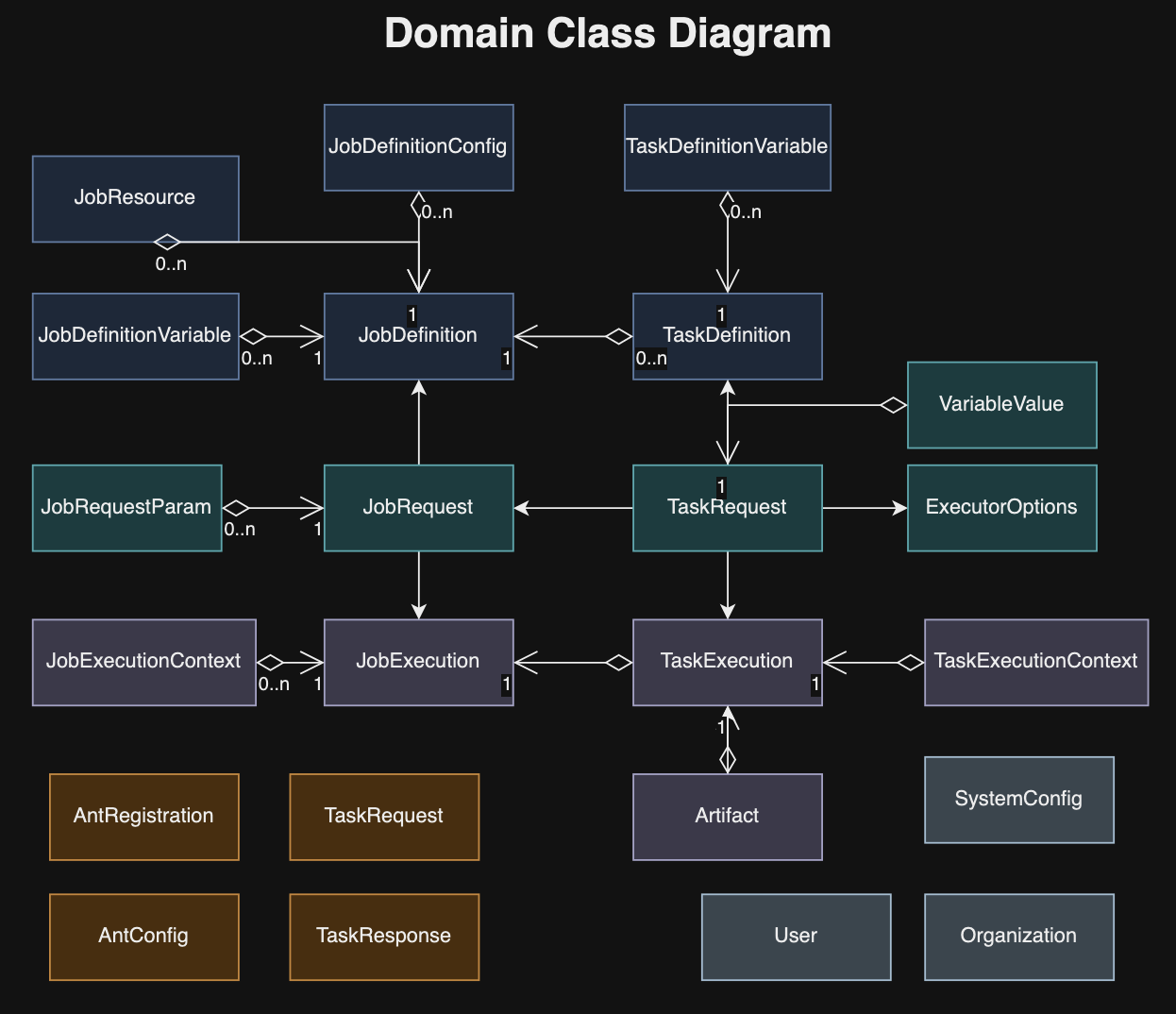

Understanding the Technology

- Determine whether the existing technology is effective

- Learn how high-impact technical decisions are made

- Build a trivial change and deploy it

- Do an on-call rotations

- Attend incident reviews

- Record the technology history

- Document the existing technology strategy

3. Writing Your Engineering Strategy

The defines an Engineering strategy document as follows:

- The what and why of Engineering’s resource allocation against its priorities

- The fundamental rules that Engineering’s team must abide by

- How decisions are made within Engineering

Defining Strategy

According to Richard Rumelt’s Good Strategy, Bad Strategy, a strategy is composed of three parts:

- Diagnosis to identify root causes at play

- Guiding policies with trade-offs

- Coherent actions to address the challenge

Writing Process

The author recommends following risk management process for writing an Engineering strategy:

- Commit to writing this yourself!

- Focus on writing for the Engineering team’s leadership (executive and IC).

- Identify the full set of stakeholders you want to align the strategy with.

- From within that full set of stakeholders, identify 3-5 who will provide early rapid feedback.

- Write your diagnosis section.

- Write your guiding policies.

- Now share the combined diagnosis and guiding policies with the full set of stakeholders.

- Write the coherent actions.

- Identify individuals who most likely will disagree with the strategy.

- Share the written strategy with the Engineering organization.

- Finalize the strategy, send out an announcement and commit to reviewing the strategy’s impact in two months.

When to Write the Strategy

The author recommends asking three questions to ask before getting started:

- Are you confident in your diagnosis or do you trust the wider Engineering organization to inform your diagnosis?

- Are you willing and able to enforce the strategy?

- Are you confident the strategy will create leverage?

Dealing with Missing Company Strategies

Many organizations have Engineering strategies but they are not written. The author recommends focusing on non-Engineering strategies that are most relevant to Engineering and documenting their strategies yourself. Some of the questions that should be in these draft strategies include:

- What are the cash-flow targets?

- What is the investment thesis across functions?

- What is the business unit structure?

- Who are products’ users?

- How will other functions evaluate success over the next year?

- What are most important competitive threats?

- What about the current strategy is not working?

Establishing the Diagnosis

The author offers following advice on writing an effective diagnosis:

- Don’t skip writing the diagnosis.

- When possible, have 2-3 leaders diagnose independently.

- Diagnose with each group of stakeholder skeptics.

- Be wary when your diagnosis is particular similar to that of your previous roles.

Structuring Your Guiding Policies

The author recommends starting with following key questions:

- What is the organization’s resource allocation against its priorities (And why)?

- What are the fundamental rules that all teams must abide by?

- How are decisions made within Engineering?

Maintaining Your Guiding Policies’ Altitude

To ensure your strategy is operating at the right altitude, the author recommends asking if each of your guiding policies is applicable, enforced and creates leverage with multiplicative impact.

Selecting Coherent Actions

The author recommends three major categories of coherent actions:

- Enforcement

- Escalations

- Transitions to the new state

4. How to Plan

This chapter discusses the default planning process, phases of planning and exploring frequent failure modes.

The Default Planning Process

Most organizations have yearly, quarterly or mid-year documented planning process where teams manage their own execution against the quarter and have a monthly execution review.

Planning’s Three Discrete Phases

Effective planning process requires doing following actions well:

- Set your company’s resource allocation, across functions, as documented in an annual financial plan.

- Refresh your Engineering strategy’s resource allocation, with a particular focus on Engineering’s functional portfolio allocation between functional priorities and business priorities.

- Partner with your closes cross-functional partners to establish a high-level quarter or half roadmap.

Phase 1: Establishing Your Financial Plan

The financial plan includes three specific documents:

- A P&L statement showing revenue and cost, broken own by business line and function.

- A budget showing expenses by function, vendors, and headcount.

- A headcount plan showing the specific roles in the organization.

How to Capitalize Engineering Costs

Finance team follows the Generally Accepted Account Principles (GAAP). The Engineering and Finance can choose one of three approaches:

- Ticket-based

- Project-based

- Role-based

The Reasoning behind Engineering’s Role in the Financial Plan

The author recommends segmenting Engineering expenses by business line into three specific buckets:

- Headcount expenses within Engineering

- Production operating costs

- Development costs

Why should Financial Planning be an Annual Process?

- Adjusting your financial plan too frequently makes it impossible to grade execution.

- Making significant adjustments to your financial plan requires intensive activity.

- Like all good constraints, if you make the plan durable, then it will focus teams on executing effectively.

Attributing Costs to Business Units

Attributions get messy as you dig in so author recommends a flexible approach with Finance.

Why can Financial Planning be so Contentious?

The author recommends escalation with CEO if financial planning becomes contentious.

Should Engineering Headcount Growth Limit Company Headcount Growth?

The author recommends constraining overall headcount growth based on their growth rate for Engineering.

Incoming Organizational Structure

- Divide your total headcount into teams of eight with a manager and a mission.

- Group those teams into clusters of four to six with a focus area.

- Continue recursively grouping until you get down to 5-7 groups, which will be your direct reports.

Aligning the Hiring Plan and Recruiting Bandwidth

The author recommends comparing historical recruiting capacity against the current hiring plan.

Phase 2: Determining Your Functional Portfolio Allocation

This phase involves allocating the functional portfolio and deciding how much engineering capacity should be dedicated to stakeholder requests versus internal priorities each month over the next year. The author recommends following approach:

- Review full set of Engineering investments, their impact and the potential investment.

- Update this list on a real-time basis as work completes.

- As the list is updated, revise target steady-state allocation to functional priorities.

- Spot fixing the large allocations that are not returning much impact.

Why do we need Functional Portfolio Allocation?

The functional planning is best done by the responsible executive and team but you can do it in partnership with your Engineering leadership. The author recommends adding compliance, security, reliability into the functional planning process.

Keep the Allocation Fairly Steady

The author recommends continuity and narrow changes over continually pursuing an ideal allocation. This approach minimizes disruption and avoids creating zero-sum competition with peers.

Be Mindful of Allocation Granularity

Using larger granularity empowers teams to make changes independently, while more specific allocations to specific teams will require greater coordination.

Don’t Over-index on Early Results

Commit to a fixed investment in projects until they reach at least one inflection point in their impact curve.

Phase 3: Agreeing on the Roadmap

The author highlights key issues that lead to roadmapping failures:

Roadmapping with Disconnected Planners

When roadmap is not aligned with all stakeholders such as Sales and Marketing.

Roadmapping Concrete and Unscoped Work

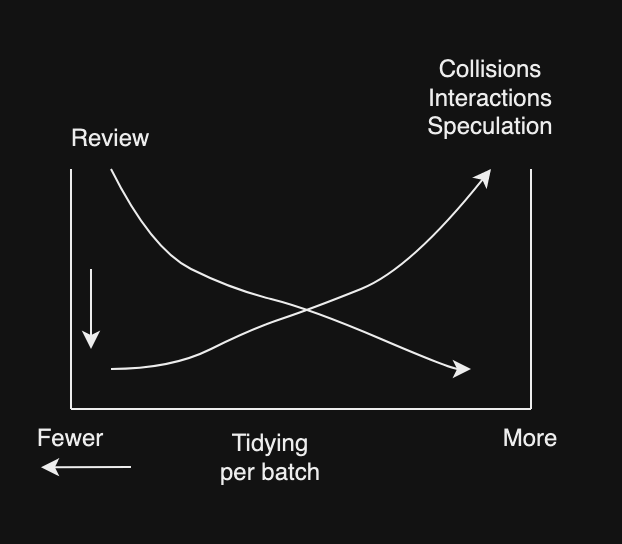

During planning process, executives may ask for new ideas, but these are often unscoped and unproven. The author suggests establishing an agreed-upon allocation between scoped and unscoped initiatives, and maintaining a continuous allocation for validating projects.

Roadmapping in Too Much Detail

The author references Melissa Perri, who recommends against roadmapping that is focused narrowly on project to-do items rather than on desired outcome.

Timeline for Planning Processes

- Annual budget should be prepared at the end of the prior year.

- Functional planning should occur on a rolling basis throughout the year.

- Quarterly planning should occur in the several weeks proceeding each quarter.

Pitfalls to Avoid

- Planning as ticking checkboxes

- Planning is a ritual rather than part of doing work.

- Planning is focused on format rather than quality.

- Planning as inefficient resource allocator

- Planning creates a budget, then ignores it.

- Planning rewards the least efficient organization.

- Planning treats headcount as a universal curve – when focused on rationalizing heacount rather than most important work.

- Planning as rewarding shiny projects

- Planning is anchored on work the executive team finds most interesting.

- Planning only accounts for cross-functional requests.

- Planning as diminishing ownership

- Planning is narrowly focused on project prioritization rather than necessary outcome.

- Planning generates new projects.

5. Creating Useful Organizational Values

This chapter delves into organizational values, exploring how to establish them and assess their effectiveness.

What Problems Do Values Solve?

- Values increase cohesion across the new and existing team as the organization grows.

- Formalize cultural changes so it persists over time.

- Prevent conflict when engineers disagree on existing practices and patterns.

Should Engineering Organization Have Values?

Some values aren’t as relevant outside of Engineering and other values might work well for an entire company.

What Makes a Value Useful?

- Reversible: It can be rewritten to have a different or opposite perspective without being nonsensical.

- Applicable: It can be used to navigate complex, real scenarios, particularly when making trade-offs.

- Honest: It accurately describe real behavior.

How are Engineering Values Distinct from a Technology Strategy?

Some guiding principles from an engineering strategy might resemble engineering values, but guiding principles typically address specific circumstances.

When and How to Roll Out Values

The author advises focusing on honest values and rolling them out gradually by collaborating with stakeholders, testing, and iterating as needed. The author also recommends integrating values into the hiring process, onboarding, promotions and meetings.

Some Values I’ve Found Useful

The author shares some of the values:

- Create capacity (rather than capture it).

- Default to vendors unless it’s our core competency.

- Follow existing patterns unless there’s a need for order of magnitude improvements.

- Optimize for the [whole, business unit, team].

- Approach conflict with curiosity.

6. Measuring Engineering Organizations

This chapter focuses on measuring Engineering organizations to build software more effectively.

Measuring for Yourself

The author recommends following buckets:

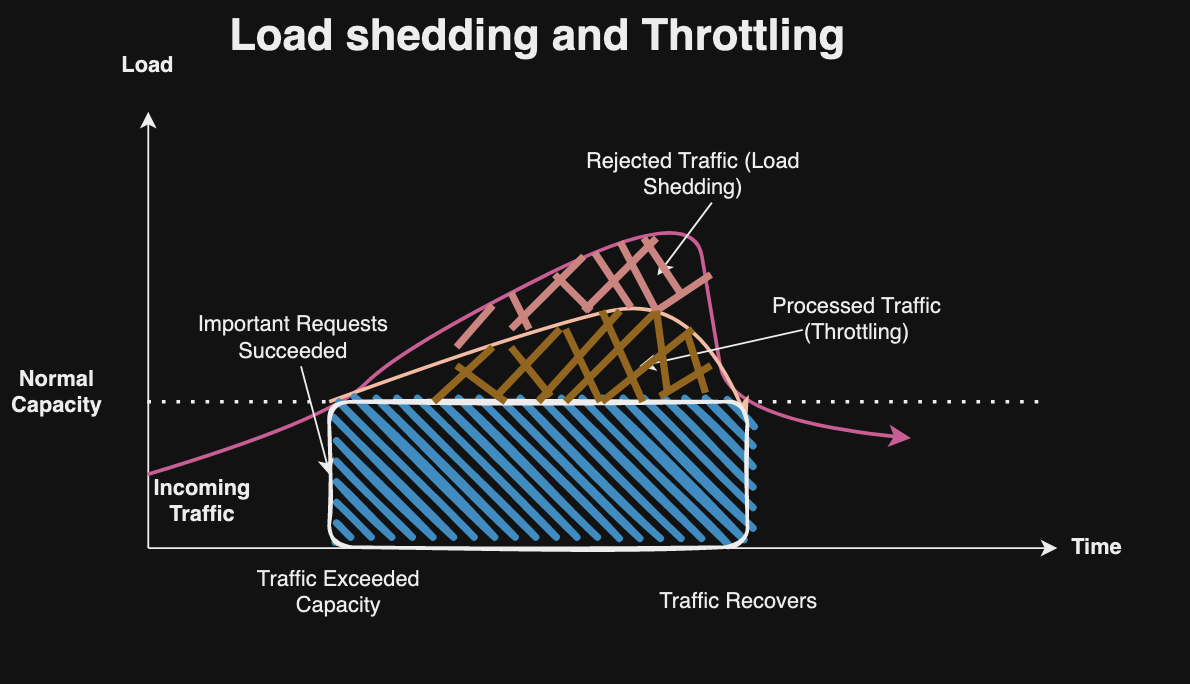

- Measure to Plan – track the number of shipped projects by team and their impact.

- Measure to Operate – track the number of incidents, downtime, latency, cost of APIs.

- Measure to Optimize – SPACE framework.

- Measure to Inspire and Aspire.

Measuring for Stakeholders

- Measure for your CEO or your board

- Measure for Finance

- Measure for strategic peer organizations

- Measure for tactical peer organizations

Sequencing Your Approach

- Some things are difficult to measure, so only measure those if you will incorporate that data into your decision making.

- Some things are easy to measure, so measure those to build trust with your stakeholders.

- Whenever possible, only take on one new measurement task at a time.

Antipatterns

- Focusing on measurement when the bigger issue is a lack of trust.

- Letting perfect be the enemy of good.

- Using optimization metrics to judge performance.

- Measuring individuals rather than teams.

- Worrying too much about measurements being misused.

- Deciding alone rather than in community.

Building Confidence in Data

- Review the data on a weekly cadence.

- Maintain a hypothesis for why the data changes.

- Avoid spending too much time alone with the data.

- Segmenting data to capture distinct experiences.

- Discuss how the objective measurement corresponds with the subjective experience.

7. Participating in Mergers and Acquisitions

This chapter explores the incentives for acquiring another company, developing a shared vision, and the processes involved in engineering evaluation and integration.

Complex Incentives

Mergers and acquisitions often involve miscommunication about the technology being acquired and its integration or replacement within the existing stack. This can lead to misaligned incentives, such as the drive to increase revenue if the integration process is overly complex.

Developing a Shared Perspective

The author recommends following tools to evaluate an acquisition:

- Business strategy

- Acquisition thesis

- Engineering evaluation

Business Strategy

The author recommends asking following questions:

- What are your business lines?

- What are your revenue and cash-flow expectations for each business line?

- How do you expect M&A to fit into these expectations?

- Are you pursuing acquihires, product acquisitions or business acquisitions?

- What kinds and sizes of M&A would you consider?

Common M&Q strategies include:

- Acquring revenue or users for your core business.

- Entering new business lines via acquisition.

- Driving innovation by acquiring startups in similar spaces.

- Reducing competition.

Acquisition Thesis

Acquisition thesis is how a particular fits into your company’s business strategy including product capabilities, intellectual property, revenue, cash flow and other aspects.

Engineering Evaluation

The author recommends following approach:

- Create a default template of topics and questions to cover in every acquisition.

- For each acquisition, for that template and add specific questions for validation.

- For each question or topic, ask the Engineering contact for supporting material.

- After reviewing those materials, schedule discussion with the Engineering contact for all yet-to-be-validated assumptions.

- Run the follow-up actions.

- Sync with the deal team on whether it makes sense to move forward.

- Potentially interview a few select members of the company to be acquired.

Recommended Topics for an Engineering Evaluation Template

- Product implementation

- Intellectual property

- Security

- Compliance

- Integration mismatches

- Costs and scalability

- Engineering culture

Making an Integration Plan

The author recommends following approach:

- Commit to running the acquired stack “as is” for first six months and consolidate technologies wherever possible.

- Bring the acquired Engineering team over and combine vertical teams.

- Be direct and transparent with any senior leaders about roles where they could step in.

Three important questions to work through are:

- How will you integrate the technology?

- How will you integrate the teams?

- How will you integrate the leadership?

Dissent Now or Forever Hold Your Peace

The author recommends anchoring feedback to the company’s goals rather than Engineering’s.

8. Developing Leadership Styles

This chapter covers leadership styles and how to balance across those styles.

Why Executives Need Several Leadership Styles

The author recommends working with the policy as it empowers the organization to move quickly but you still need to guide operations to handle exceptions.

Leading with Policy

It involves establishing a documented and consistent process for decision-making such as determining promotions. The core mechanics are:

- Identify a decision that needs to be made frequently.

- Examine how decisions are currently being made and structure your process around the most effective decision-makers.

- Document that methodology into a written policy with feedback from the best decision makers.

- Roll out the policy.

- Commit to revisiting the policy with data after a reasonable period.

Leading from Consensus

It involves gathering the relevant stakeholders to collaboratively identify a unified approach to addressing the problem. The core mechanics include:

- It is specially applicable when there are many stakeholders and none of them has the full and relevant context.

- Evaluate whether it’s important to make a good decision (one-way vs two-way).

- Identify the full set of stakeholders to include the decision.

- Write a framing document capturing the perspectives that are needed from other stakeholders.

- Identify a leader to decide how group will work together on the decision and deadline for the decision.

- Follow that leader’s direction on building consensus.

Leading with Conviction

It involves absorbing all relevant context, carefully considering the trade-offs, and making a clear, decisive choice. The core mechanics include:

- Identify an important decision to make a high-quality decision.

- Figure out the individuals with the most context and deep dive them to build a mental model of the problem space.

- Pull that context into a decision that you write down.

- Test the decision widely with folks who have relevant context.

- Tentatively make the decision that will go into effect a days in the future.

- Finalize the decision after your timeout and move forward to execution.

- In order to show how you reach the decision, write down your decision making process.

Development

The author recommends following steps to get comfortable with leadership styles:

- Set aside an hour to collect the upcoming problems once a month.

- Identify a problem that might require using a style that you don’t use frequently.

- Do a thought exercise of solving that scenario using that leadership style.

- Review your thoughts exercise with someone.

- Think about how scenario can be solved using a style you’re more comfortable with.

- If the alternative isn’t much worse and stakes aren’t exceptionally high, then use the style you’re less comfortable with.

9. Managing Your Priorities and Energy

This chapter discusses prioritization, energy management and being flexible.

“Company, Team, Self” Framework

The author suggests using this framework to ensure engineers don’t create overly complex software solely for career progression but also acknowledges that engineers can become demotivated if they’re not properly recognized for addressing urgent issues.

Energy Management is Positive-Sum

Managers may get energy from different activities such as writing software, mentoring, optimizing existing systems, etc. However, energizing work needs to avoid creating problems for other teams.

Eventual Quid Pro Quo

The author cautions against becoming de-energized or disengaged in any particular job and offers “eventual quid pro quo” framework:

- Generally, prioritize company and team priorities over my own.

- If getting de-energized, prioritize some energizing work.

- If the long-term balance between energy and priorities can’t be achieved, work on solving it.

10. Meetings for an Effective Engineering Organization

This chapter digs into the need of meetings and how to run meetings effectively.

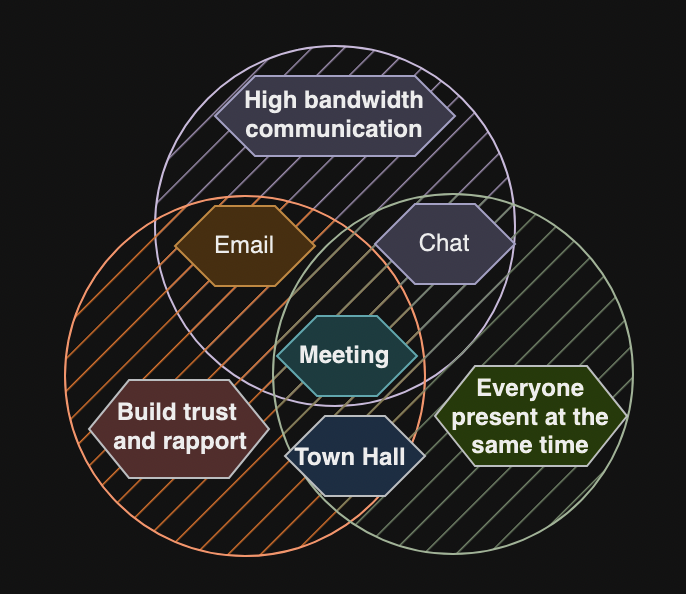

Why Have Meetings?

Meetings help distribute context down the reporting hierarchy, communicate culture and surface concerns from the organizations.

Six Essential Meetings

Weekly Engineering Leadership Meeting

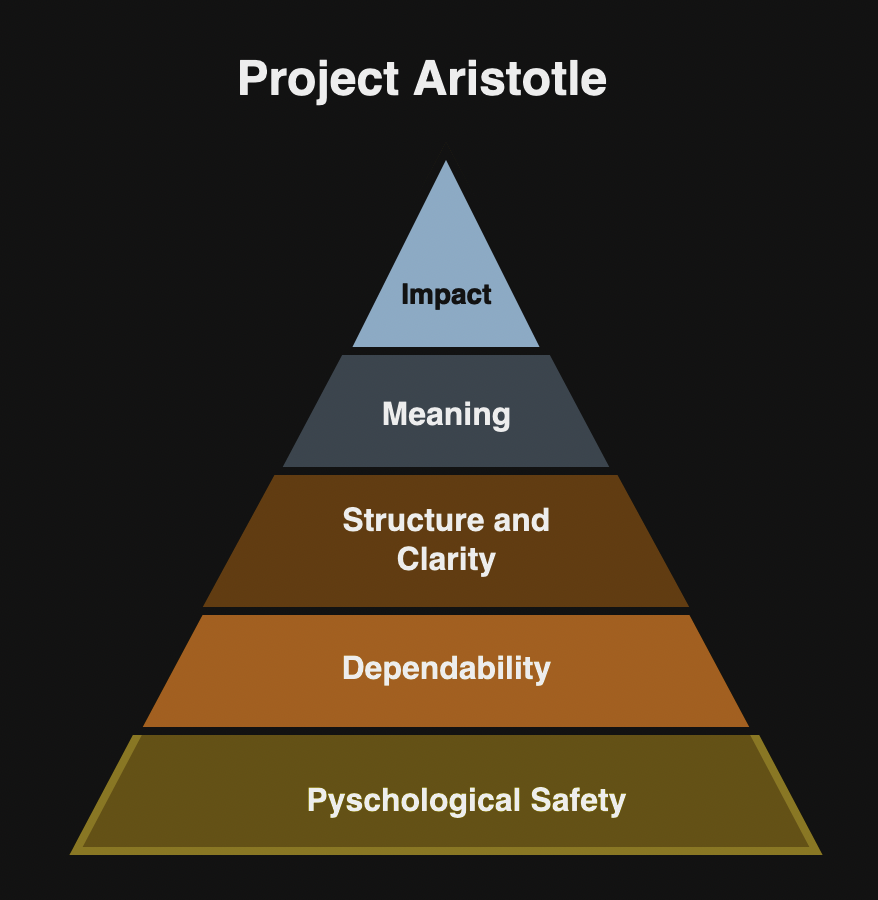

This meeting is a working session for your leadership team to accomplish things together. It allows teams to share context with others and support each other with a “first team” (See The Five Dysfunctions of a Team). Authors offers following suggestions:

- Include direct reports and key partners.

- Maintain a running agenda in a group-editable document.

- Meet weekly.

Weekly Tech Spec Review and Incident Review

This meeting is a weekly session for discussing any new technical specs or incidents. The author offers following suggestions:

- All reviews should be anchored to a concise, clearly written document.

- Reading the written document should be a prerequisite to providing feedback on it (start with 0 minutes to read the document).

- Good reviews are anchored to feedback from the audience and discussion between the author and the audience.

- Document a simple process for getting your incident writeup or tech spec scheduled.

- Measure the impact of these review meetings by monitoring participation.

- Find dedicated owner for each meeting.

Monthlies with Engineering Managers and Staff Engineers

The format of this meeting includes:

- Ask each member to share something they’re working on or worried about.

- Present a development topic like P&L statement.

- Q&A

Monthly Engineering Q&A

- Have a good tool for taking questions.

- Remind folks the day before the meeting.

- Highlight individuals doing important work.

What About Other Meetings?

- 1:1 meetings

- Skip-level meetings

- Execution meetings

- Show-and-tells

- Tech talks or Lunch-and-Learns

- Engineering all-hands

Scaling Meetings

- Scale operational meetings to optimize for right participants.

- Scale development meetings to optimize for participant engagements.

- Keep the Engineering Q&A as a whole organization affair.

11. Internal Communication

This chapter covers practices to improve quality of internal communication.

Maintain the Drip

The author recommends sending a weekly update to let the team know what you are focused on. You can maintain a document that accumulate weekly documents and then compile them into an email. The weekly update is generally structured as follows:

- 1-2 sentences that energized me this week.

- One sentence summarizing any key reminders for upcoming deadlines.

- One paragraph for each important topic that has come up over the course of the week, e.g., product launch, escalation, planning updates.

- A bulleted list of brief updates like incident reviews, a tech spec or product design.

- Invitation to reach out with questions and concerns.

Test Before Broadcasting

The author recommends proofreading and asking for feedback from individuals before sharing the updates widely.

Build the Packet

The author recommends following structure for important communication:

- Summary

- Canonical source of information

- Where to ask questions

- Keep it short

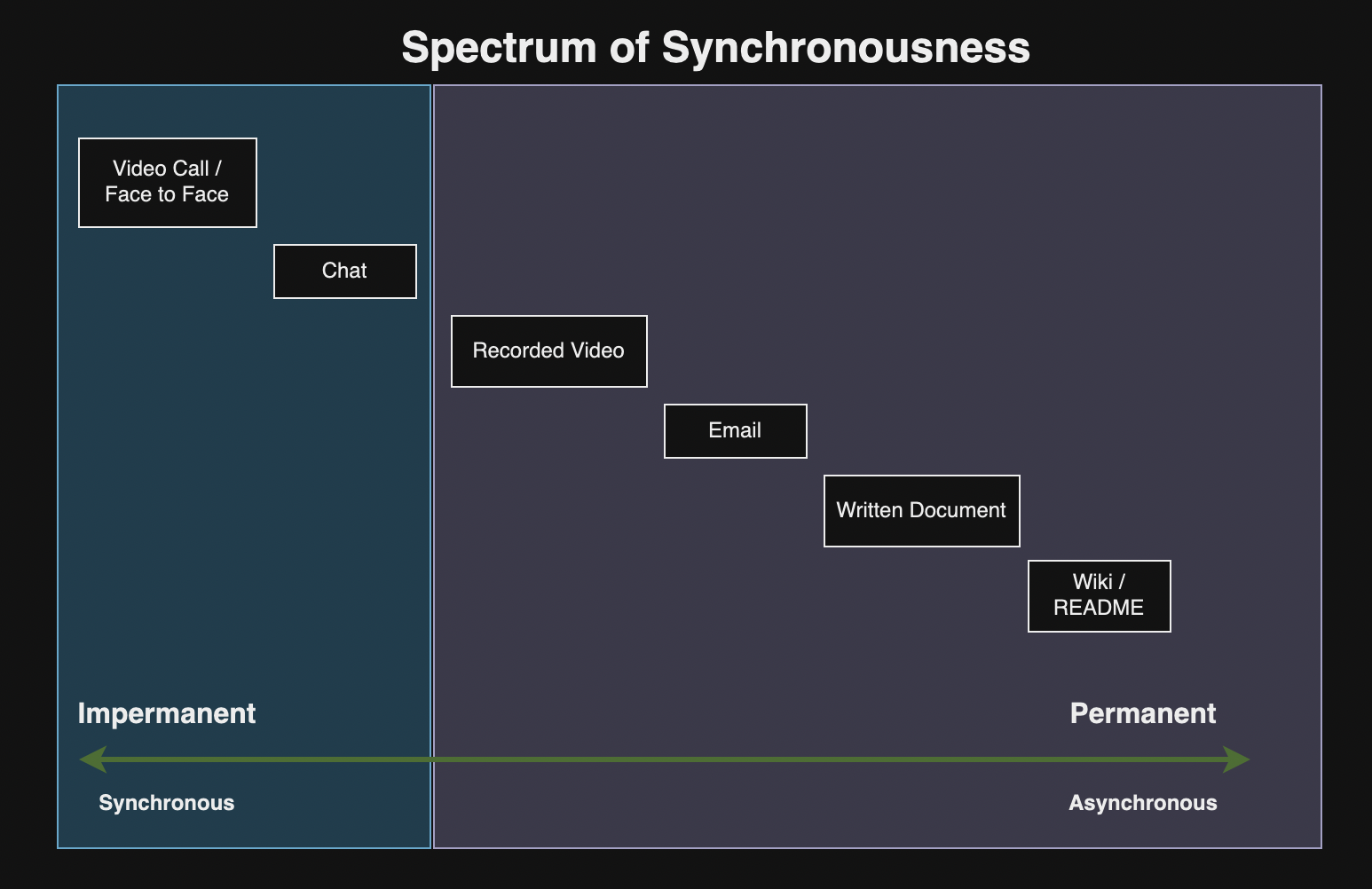

Use Every Channel

- Email and chat

- Meetings

- Meeting minutes

- Weekly notes

- Decision log

12. Building Personal and Organizational Prestige

This chapter covers building prestige, brand and an audience.

Brand Versus Prestige

A brand is a carefully constructed, ongoing narrative that defines how you’re widely known. Prestige, on the other hand, is the passive recognition that complements your brand. The author suggests the following methods to build prestige:

- As an individual – attend a well-respected university, join well-known company.

- As a company – problem that is attractive to software engineer.

Manufacturing Prestige with Infrequent, High-Quality Content

The author recommends following approach:

- Identify a topic where you have a meaningful perspective.

- Pick a format that feels the most comfortable for you.

- Create the content!

- Develop an explicit distribution plan for sharing your content.

- Make it easy for interested parties to discover your writing.

- Repeat this process two to three times over the next several years.

Measuring Prestige is a Minefield

- Pageviews

- Social media followers

- Sales

- Volume

13. Working with Your CEO, Peers, and Engineering

This chapter discusses topics related to building effective relationships.

Are You Supported, Tolerated, or Resented?

You can check the status of your relationship with other parts of your company:

- Supported – when others proactively support your efforts.

- Tolerated – when others are indifferent to your work.

- Resented – when other view your requests as a distraction.

Navigating the Implicit Power Dynamics

The author recommends listening closely to the CEO, the board and peers but be open to other perspectives who are doing the actual work.

Bridging Narratives

The author suggests taking time to consider a variety of perspectives and adopting a company-first approach before rushing to solve a problem.

Don’t Anchor to Previous Experience

The author advises against simply applying lessons from previous companies. Instead, they recommend first understanding how others solve problems and then asking why they chose that approach.

Fostering an Alignment Habit

The author suggests asking for feedback on what you could have done better or what you might have avoided altogether.

Focusing on Small Number of Changes

In order to retain the support of your team and peers, the author recommends focusing on delivering a small number of changes with meaningful impact.

Having Conflict is Fine, Unresolved Conflict is Not

Conflict isn’t inherently negative but you should avoid unresolved, recurring conflict. The author recommends structured escalation such as:

- Agree to resolve the conflict with the counterparty.

- Prioritize time with the counterparty to understand each other’s perspective.

- Perform clean escalation with a shared document.

- Commit to following the direction from whomever both parties escalated to.

14. Gelling Your Engineering Leadership Team

The Five Dysfunctions of a Team introduces the concept of your peers being your “first team” rather than your direct reports. This alignment is difficult and this chapter discusses gelling your leadership into an effective team.

Debugging and Establishing the Team

When starting a new executive role, the author recommends asking following questions:

- Are there members of the team who need to move on immediately?

- Are there broken relationship pairs within your leadership team.

- Does your current organizational structure bring the right leaders into your leadership team?

Operating Your Leadership Team

Operating team effectively requires following:

- Define team values

- Establish team structure

- Find space to interact as individuals

- Referee defection from values

Expectations of Team Members

The author recommends set explicit expectations on following for the team members.

- Leading their team.

- Communicating with peers.

- Staying aligned with peers.

- Creating their own leadership team.

- Learning to navigate you, their executive, effectively.

Competition Amongst Peers

The author lists following three common causes of competition:

- A perceived lack of opportunity

- The application of poor habits from bureaucratic companies

- The failure of a leader to referee their team

15. Building Your Network

This chapter covers building and leveraging your network effectively.

Leveraging Your Network

The author recommends reaching out your network when you can’t solve a problem with your team and peers.

What’s the Cheat Code?

Building your network has no shortcuts; it takes time, and you’ll need to be valuable to others within it.

Building the Network

The author advises being deliberate in expanding your network, with a focus on connecting with those who have the specific expertise you’re seeking.

- Working together in a large company in a central tech hub.

- Cold outreach with a specific question.

- Community building

- Writing and speaking

- Large communities

- What doesn’t work – ambiguous or confusing requests or lack of mutual value.

Other Kinds of Networks

- Founders

- Venture Capitalists

- Executive Recruiters

16. Onboarding Peer Executive

This chapter breaks down onboarding peer executives.

Why This Matters

A high-performing executive ensures their peers excel by providing support, including assistance with onboarding.

Onboarding Executives Versus Onboarding Engineers

When onboarding engineers, you share a common field of software engineering. However, when onboarding executives, they may come from different fields. Your goal should be to help them understand the current processes and the company’s landscape by involving them in a project or addressing critical issues.

Sharing Your Mental Framework

- Where can the new executive find real data to inform themselves?

- What are the top to three problems they should immediately spend time fixing?

- What is your advice to them regarding additional budget and headcount requests?

- What are areas in which many companies struggle but are currently going well here?

- What is your honest but optimistic read on their new team?

- What do they need to spend time with to understand the current state of the company?

- What is going to surprise them?

- What are the key company processes?

Partnering with an Executive Assistant

- When to hire

- Leveraging support

- Managing time

- Drafting communications

- Coordinating recurring meetings

- Planning off-site sessions

- Coordinating all-hands meetings

Define Your Roles

- What are your respective roles?

- How do you handle public conflict?

- What is the escalation process for those times when you disagree?

Trust Comes with Time

- Spend some time knowing them as a person

- Hold a weekly hour-long 1:1, structured around a shared 1:1 document

- Identify the meetings where your organization partner together to resolve prioritization

17. Inspected Trust

This chapter covers how relying on trust heavily can undermine leadership and and using tools instead of relying exclusively on trust.

Limitations of Managing Through Trust

A new hire begins with a reserve of trust, but if they start burning it, their manager might not provide the necessary feedback. A good manager should prioritize accountability over relying too heavily on trust.

Trust Alone isn’t a Management Technique

Trust cannot distinguish between the good and bad variants of work:

- Good errors – Good process and decisions, bad outcome

- Bad errors – Bad process and decision, bad outcome

- Good success – Good process and decision, good outcome

- Bad successes – Bad process and decisions, good outcome

Why Inspected Trust is Better

The author recommends inspected trust instead of blind trust.

Inspection Tools

- Inspection forums – weekly/monthly metric review forum

- Learning spikes

- Engaging directly with data

- Handling a fundamental intolerance for misalignment

Incorporating Inspection in Your Organization

- Don’t expand everywhere all at once; instead focus on 1-2 critical problems.

- Figure out your peer executives’ tolerance for inspection forums.

- Explain to your Engineering leadership what you are doing?

18. Calibrating Your Standards

This chapter covers standards can cause friction and matching your standards with your organization standards.

The Peril of Misaligned Standards

You may want to hire folks with very high standards but organizations only tolerate a certain degree of those expectations.

Matching Your Organization’s Standards

The author argues that a manager is usually aware of an underperformer’s issues but often fails to address them, which is a mistake. In some companies, certain areas may operate with lower standards due to capacity constraints or tight deadlines.

Escalate Cautiously

When your peers are not meeting your standards, the author recommends leading escalation with constructive energy directed toward a positive outcome.

Role Modeling for Your Peers

The author suggests following playbook to improve an area that you care about:

- Model – Identify the area and demonstrate a high-standards approach through role modeling.

- Document – Document the approach once it is working.

- Share – Send the documented approach to the teams you want to influence.

Adapting Your Standards

The author suggests taking time to determine what matters most to you when your standards exceed those of the organization.

19. How to Run Engineering Processes

This chapter explores patterns for managing processes and how companies evolve through them.

Typical Pattern Progression

The author defines following patterns for running Engineering:

- Early Startup – small companies (30-50 hires)

- Baseline – 50 hires

- Specialized Engineering roles – 200 hires – incident review / tech spec review / TPM / Ops

- Company Embedded Roles – specialized roles – developer relations / TPM /QE / SecEng

- Business Unit Local – Engineering reports into each business unit’s leadership

Patterns Pros and Cons

Early Startup

- Pros: Low cost and low overhead

- Cons: Quality is low and valuable stuff doesn’t happen

Baseline

- Pros: Modest specialization to focus on engineering; Unified systems to inspect across functions

- Cons: Outcomes depend on the quality of centralized functions

Specialized Engineering Roles

- Pros: Specialized roles introduce efficiency and improvements

- Cons: More expensive and freeze a company in a given way of working and specialists incentivized to improve processes instead of eliminating them

Company Embedded Roles

- Pros: Engineering can customize its process and approach

- Cons: Expensive to operate and quality depends on embedded individuals

Business Unit Local

- Pros: Aligns Engineering with business priorities

- Cons: Engineering processes and strategies require consensus across many leaders

Early Startup

- Pros: Low cost and low overhead

- Cons: Quality is low and valuable stuff doesn’t happen

20. Hiring

This chapter covers hiring process, managing headcounts, training and other related topics.

Establish a Hiring Process

The author recommends a hiring process with following components:

- Application Tracking System (ATS)

- Interview definition and rubric – set of questions for each interview

- Interview loop documentation – for every role

- Leveling framework – based on interview performance

- Hiring role definitions

- Job description template

- Job description library

- Hiring manager and interviewer training

Pursue Effective Rather than Perfect

The author warns against implementing overly burdensome processes that consume significant energy without yielding much impact, such as adding extra interviews in hopes of a clearer signal. Instead, the author recommends setting a high standard for any additions to your hiring process.

Monitoring Hiring Process and Problems

The author offers following mechanisms for monitoring and debugging hiring:

- Include Recruiting in your weekly team meeting

- Conduct a hiring review meeting

- Maintain visibility into hiring approval

- Approve out-of-band compensation

- Review monthly hiring statistics

Helping Close Key Candidates

An executive can help secure senior candidates by sharing the Engineering team’s story and highlighting why it offers compelling and meaningful work.

Leveling Candidates

The author recommend executives to level candidate before they start the interview process. The approach for leveling decision includes:

- A final decision is made by the hiring manager.

- Approval is done by the hiring manager’s manager for senior roles.

Determining Compensation Details

- The recruiter calculates the offer and shares it into a private channel with the hiring manager.

- Offer approvers are added to the channel to okay the decision.

- Offers following standard guidelines.

- Any escalation occur within the same private chat.

Managing Hiring Prioritization

The author suggests a centralized decision-making process for evaluating prioritization by assigning headcount and recruiters to each sub-organization, allowing them to optimize their priorities.

Training Hiring Managers

The author recommends training hiring managers to avoid problems such unrealistic demands, non-standard compensation, being indecisive, etc.

Hiring Internally and Within Your Network

The author advises distancing yourself from the decision-making process when hiring within your network. Additionally, the author recommends exercising moderation when hiring, whether internally, externally, or within your own network.

Increasing Diversity with Hiring

The author warns against placing the responsibility for diversity solely on Recruiting, emphasizing that Engineering should also be held accountable for diversity efforts.

Should You Introduce a Hiring Committee?

Hiring committees can be valuable, but the author cautions against relying on them as the default solution, as they can create ambiguity about accountability and distance from the team the candidate will join. An alternative approach is to implement a Bar Raiser, similar to Amazon’s hiring process.

21. Engineering Onboarding

The chapter examines key components of effective onboarding, focusing on the roles of the executive sponsor, manager, and buddy in a typical process. It explores how these positions contribute to successfully integrating new employees into an organization.

Onboarding Fundamentals

A structured onboarding process defines specific curriculum based on roles:

Roles

- Executive sponsor – select the program orchestrator to operate the program.

- Program orchestrator – Develop and maintain the program’s curriculum.

Why Onboarding Programs Fail

The onboarding programs often due to lack of sustained internal engagement or the program becomes stale and bureaucratic.

22. Performance and Compensation

This chapter covers designing, operating and participating in performance and compensation processes.

Conflicting Goals

A typical process at a company tries to balance following stakeholders:

- Individuals – they want to get useful feedback so they can grow.

- Managers – provide fair and useful feedback to their team.

- People team (or HR) – ensure individuals receive valuable feedback.

- Executives – decide who to promote based on evaluations.

Performance and Promotions

Feedback Sources

The feedback generally comes from peers and the manager. However, peer feedback can take up a significant amount of time and often is inconsistent.

Titles, Levels, and Leveling Rubrics

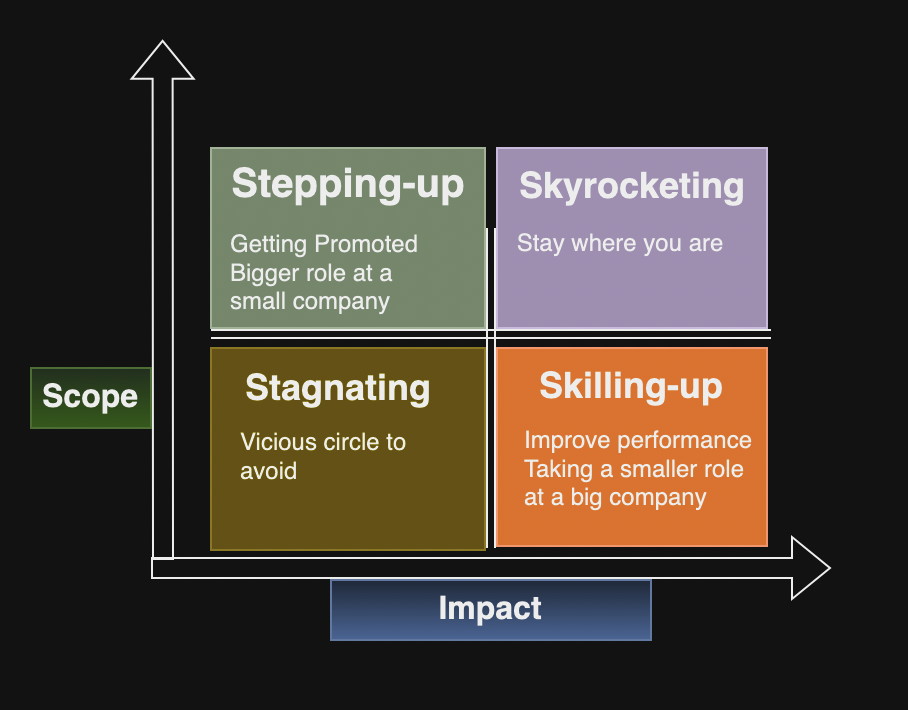

The author outlines a typical career progression in software engineering: Entry-level, Software Engineer, Senior Software Engineer, and Staff Software Engineer. They recommend creating concise leveling rubrics that describe expectations for each level, favoring broad job families over narrow ones. These guidelines aim to provide clear career paths while maintaining flexibility across different company structures.

Promotions and Calibration

A common calibration process looks like:

- Managers submit their tentative ratings and promotion decisions.

- Managers in a sub-organization meet together to discuss tentative decisions.

- Managers re-review tentative decisions for the entire organization.

- The Engineering executive reviews the final decisions and aligns with other executives.

Compensation

- Build compensation bands by looking at aggregated data from compensation benchmarking companies.

- Compensation benchmarking is always done against a self-defined peer group.

- Discuss compensation using the compa-ratio.

- Geographical adjustment component.

23. Using Cultural Survey Data

This chapter covers reading survey results and taking actions on survey data.

Reading Results

The author outlines following approach for reviewing survey data:

- Verify your access level: company-wide or Engineering report only. If limited to Engineering, raise the issue at the next executive team meeting to request broader access.

- Create a private document to collect your notes on the survey.

- Get a sense of the size of your population in the report.

- Skim through the entire report and group insights into: things to celebrate, things to address and things to acknowledge.

- Focus on highest and lowest absolute ratings.

- Focus on ratings that are changing the fastest.

- Identify what stands out when you compare across cohorts.

- Read every single comment and add relevant comments to your document.

- Review findings with a peer.

Taking Action on the Results

The author outlines following standard pattern around taking action:

- Identify serious issues, take action immediately.

- Use analysis notes to select 2-3 areas you want to invest in.

- Edit your notes and new investment areas into a document that can be shared.

- Review this document with direct reports.

- For the areas to invest, ensure you have verifiable actions to take.

- Share the document with your organization.

- Follow up on a monthly cadence on progress against your action items

- Mention these improvements in the next cultural surveying.

24. Leaving the Job

This chapter covers the decision to leave, negotiating the exit package and transitioning out.

Succession Planning Before a Transition

The planing may look like:

- In performance reviews, provide feedback to your direct reports to focus on.

- Talk to the CEO about the growth you are seeing in your team.

- Every quarter, run an audit of the meetings you attend and delegate each meeting to someone on your team.

- Go on a long vacation each year and avoid chiming in on email and chat.

Deciding to Leave

The author recommends asking following questions when executives grapple with intersection of identify and frustration:

- Has your rate of learning significantly decreased?

- Are you consistently de-energized by your work?

- Can you authentically close candidates to join your team?

- Would it be more damaging to leave in six months than today?

Am I Changing Jobs Too Often?

- If it’s less than three months, just delete it from your resume.

- If it’s more than two years, you will be able to find another role as some of your previous roles have been 3+ years.

- As long as there’s strong narrative, any duration is long enough.

- If a company reaches out to you, there is no tenure penalty.

Telling the CEO

The discussion with CEO should include:

- Departure timeline

- What you intend to do next

- Why you are departing?

- Recommended transition plan

Negotiating the Exit Package

You may get better exit package if your exit matches the company’s preference and you have a good relationship with the CEO.

Establish the Communication Plan

- A shared description of why you are leaving.

- When each party will be informed of your departure.

- Drafts of emails and announcements to be made to larger groups.

Transition Out and Actually Leave

A common mistake is to try too hard to help, instead author recommends getting out of the way and supporting your CEO and your team.