I recently read “Become a Great Engineering Leader” (currently in beta version B5.0), which introduces tools, techniques, and secrets for engineering leadership roles. The book is divided into three parts: “The Roles Defined,” “Tools, Techniques, and Time,” and “Strategy, Planning, and Execution.” Here are the key insights from the book, organized by chapter:

1. VP, Director, What?

This chapter introduces first part about the roles defined. It lays out the career tracks where a career track for an individual contributor might looks like:

- Software Engineer

- Senior Software Engineer

- Staff Engineer

- Principal Engineer

A similar career track for manager may look like:

- Engineering Manager

- Senior Engineering Manager

- Director of Engineering

- VP of Engineering

- CTO

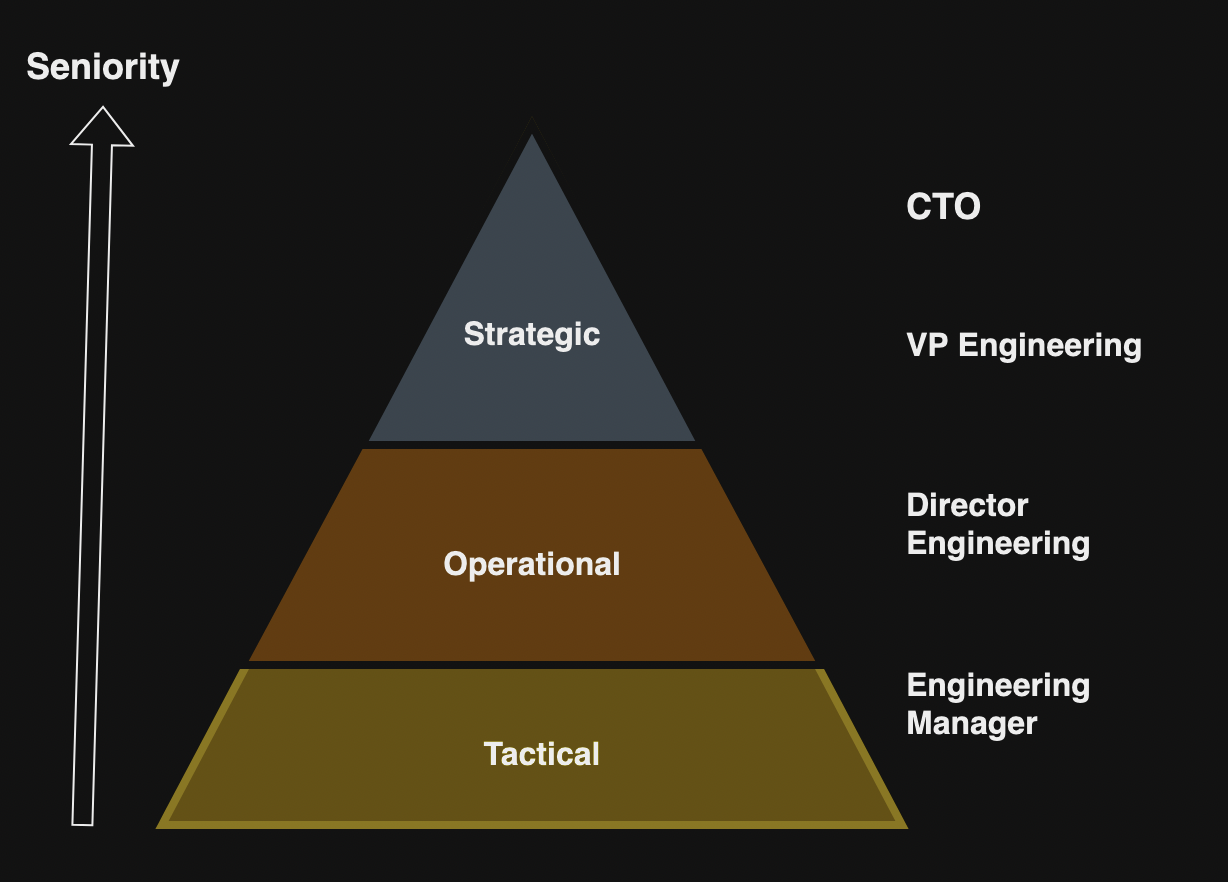

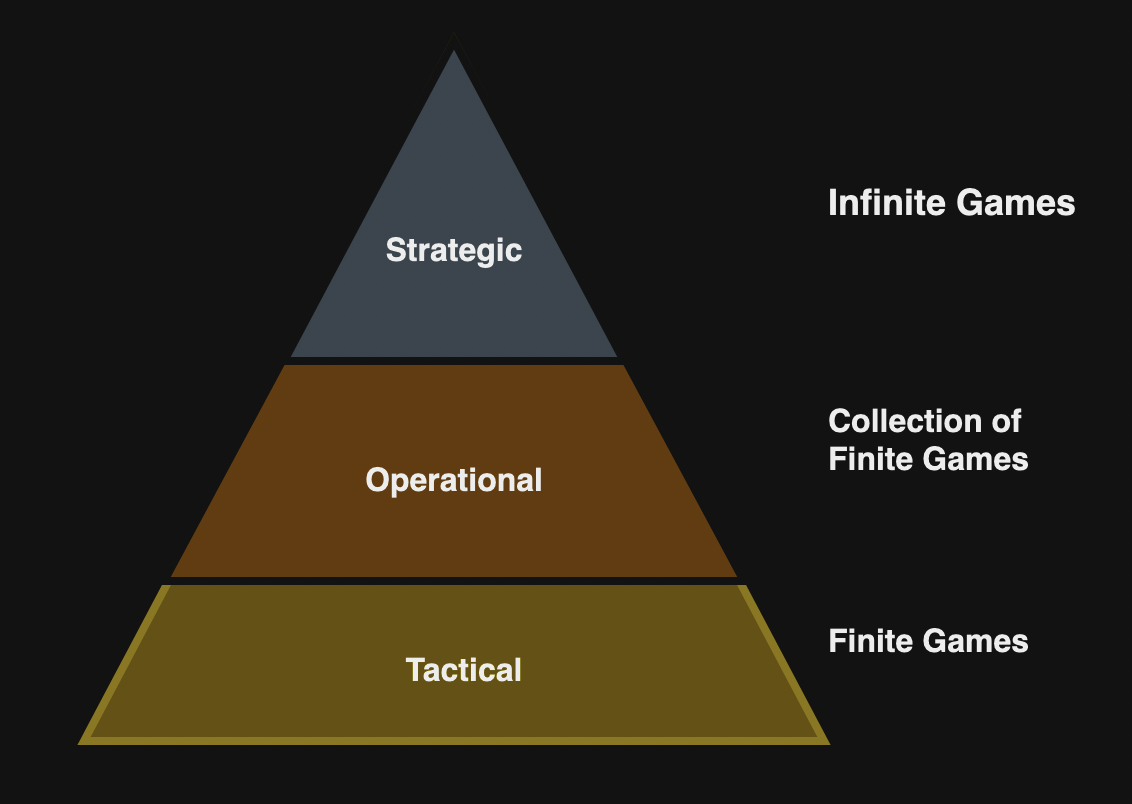

Many skills are common to both tracks and both tracks are viable options for individuals. The author cites three levels of warfare for defining responsibilities for above roles:

- Strategic

- Operational

- Tactical

The author defines scope and impact for leadership roles where the scope describes the boundaries of responsibilities and impact describes the effect the person holding the role is having. As an individual progresses through the senior roles, the impact increases that will increase the opportunities for increase of scope.

The author lists several competencies that are required to be successful in a particular role. These include:

- Professional experience

- Technical knowledge

- Mentorship

- Conflict resolution

- Communication

- Influence

2. Your Place in the Org Chart

In this chapter, the author describes how humans have become the dominant species by applying division of labor and collaboration to achieve a shared goals. The author describes org charts to show different teams, divisions and people. The org chart can help clarify who is accountable and responsible for what, relative levels of investment, encourage collaboration and avoid duplication. The author describes best practices to look shape of org chart at the tactical, operational and strategic levels.

- Span of control is the number of people that report to a manager. Some of the considerations for determining the span of control includes practical limits, the seniority of manager, the seniority of the reports, and the type of work that the team does.

- Tactical: The Engineering Manager – typically has five to ten individual contributors as direct reports.

- Senior Engineering Manager – typically has five to ten Engineering Managers as direct reports who are responsible for a larger product or service. In some cases, senior individual contributors also report to them.

- Operational: The Director of Engineering – typically has five to ten direct reports and focus around an operational area.

- Strategic: The VP of Engineering and CTO – typically has five to ten directors as direct reports who form the implementation of the strategy that the VP defines.

Structural Antipatterns

The author defines a number of structural antipatterns including:

- Spans and Modes of Operation: A manager with one or two direct reports is effectively redundant in their role. A manager with a large large becomes effectively a coordinator but a manager with fifteen or more becomes ineffective.

- Making Yourself Redundant: Managers with very few reports or low-span managers are redundant. Instead of deep hierarchy, hire an Engineering Manager to run one of the sub-teams and then run the other team by Senior Manager or Director.

- Rigidity and Self-Selection: When org charts are not periodically updated in order to match the current investment. Instead, periodically review your org chart to ensure that it is still fit for the priorities.

Flows of Communication and Collaboration

Conway’s Law

It states that “any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.” It can be used to facilitate the right collaboration and communication between teams.

Dunbar’s Number

It is a cognitive limit to the number of people that an individual can maintain stable social relationships with, which is estimated to be around 150. It can be applied to structure teams and types of collaboration and communication between them.

Team Topologies

Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais in 2019 published team topology model with following four types:

- Stream-aligned teams: typically called “product teams”, which are autonomous and cross-functional teams.

- Enabling teams: support the stream-aligned teams by owning and developing shared platforms, frameworks, and tools.

- Platform teams: enable the stream-aligned teams to work autonomously by reducing the cognitive load.

- Complicated subsystem teams: own and develop the most complex parts of the system that require specialist knowledge.

The team topology model defines three modes of interaction: Collaboration, X-as-a-service, Facilitating. The team topologies model can also be fractal. Using the org chart, you can refactor it to define the interactions between teams so that ownership of user experience, critical infrastructure and other areas is clear.

3. Time: Observed, Spent, and Allocated

This is the first chapter for the second part of the book that focus on “Tools, Techniques and Time” and discusses how time and capacity is managed and other tools can be leveraged for better time management.

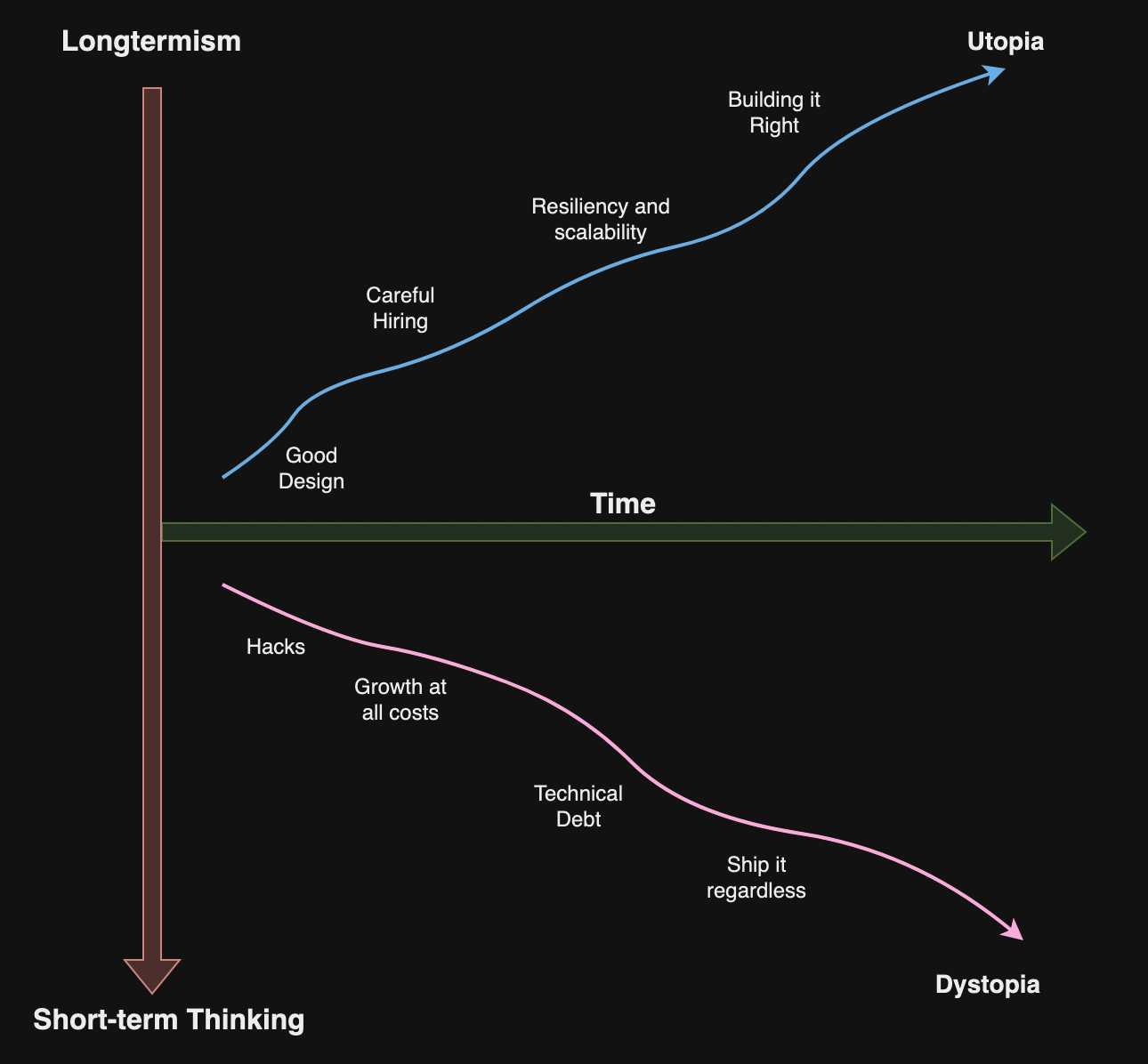

A Lens of Longtermism

The author asserts that humans can be extremely short-sighted that leads to poor decisions. The Longtermism allows making decisions that reduce major risks in the long-term future.

The author suggests following practices for longtermism:

- Ensuring that you organization’s vision and strategy is aligned with the long-term future.

- Hiring and developing the right people.

- Developing future leaders.

- Working on scalability, resilience, and reliability.

- Reducing technical debt.

Your Time Is Not Your Own

Senior leaders should spend time wisely based on the organization needs such as reviewing metrics and projects for tracking their progress, connecting and collaborating with peers and reports, strategic work, etc. The author suggests spending about 10% of time on yourself and not overcommit.

Your Capacity: Your Most Important Resource

Before managing time, you need to evaluate your capacity and the author cautions against allocating workload to your full capacity as you will need to handle escalations, meetings and other interruptions.

Managing Your Energy

The capacity is not a constant but it is a function of your energy levels. The capacity depletes when you are spending time on tasks that drain your energy and it replenishes when you work on tasks that energize you.

Input Versus Output: The Tug of War

The inputs may come from emails, meetings and interruptions and outputs are things where you add value. The author recommends keeping balance between those so that you are not in a constant state of reactivity.

Time Management: Models, Tools, and Techniques

In this section, the author goes over a number of different models, tools, and techniques for managing your time effectively.

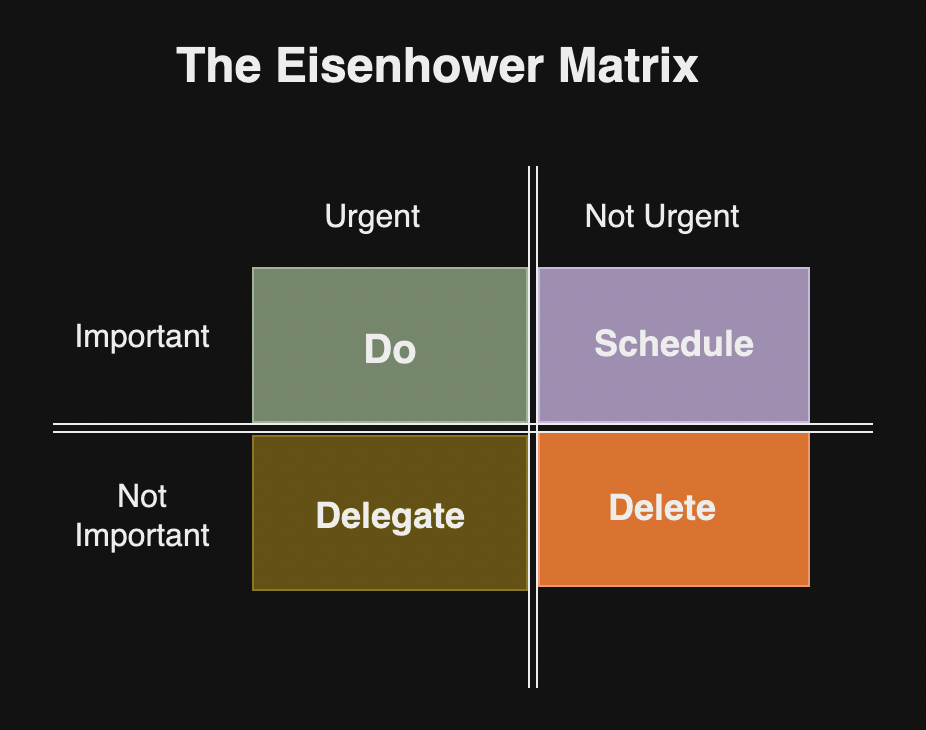

The Eisenhower Matrix

The Eisenhower Matrix consists of following 4×4 matrix:

Saying No

As your capacity is finite, and you need to ensure that you are spending it on the right things. You will have to explain the reasons for saying now and decide if it can be delegated.

Getting Executive Assistance

The executive assistance may use the Eisenhower Matrix to organize your tasks and help manage your energy.

Deadlines and Cadences: The Greatest Trick You Can Play on Yourself

Due to self-directed and future-facing work, you may fall into the trap of never getting things done. The author recommends artificial boundaries and deadline that exploits Parkinson’s Law. You can use these recurring synthetic deadlines as cadences to set goals that can be shared with the team in a sustainable way.

Using Accountability Partners

An accountability partner is someone that you trust that you can share your goals with. Your accountability partner who can also be a group (mastermind group) becomes part of your cadence.

Your Calendar: Wielding a Double-Edged Sword

This section refers to your calendar as a double-edged sword because it become a tool that others use to control you.

Blocking Time

The author recommends blocking time to ensure that you have the space to work on the things that matter. For example, you can create recurring focus time in your calendar so that others know that you are busy.

Getting the Most out of Focus Blocks

Creating the Right Environment

You can set your status to busy on any applications that support it and disable all unnecessary notifications. You can set a goal in the focus block.

The Pomodoro Technique

The Pomodoro Technique is a time management technique that was developed by Francesco Cirillo. It breaks work into intervals, typically 25 minutes in length.

Things To Focus On

You can plan on things to focus such as making progress on your goals, review the work of others or other longtermist activities. Though, the author recommends against using this time for working with your inbox but you can setup a dedicated time a few times a day to organize your inbox based on the Eisenhower Matrix.

The Power of Nothing

You can also use the focus time to brainstorm ideas, spending time using the product, read design docs or latest research.

Meetings: Crisp, Clear, and with a Purpose

Meetings are essential for certain types of communication and collaboration but they can drain your time and capacity. Some of the tips for controlling meetings include:

To Meet or Not to Meet: That Is the Question

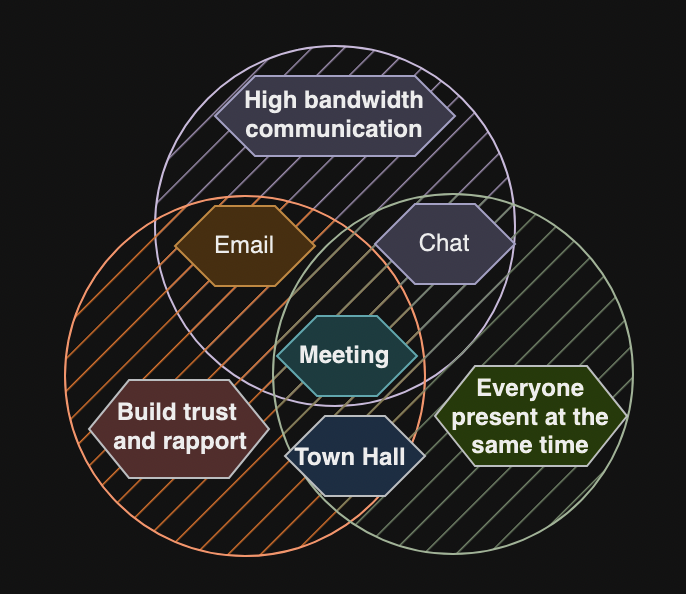

The author offers following venn diagram for meetings:

The author recommends meeting if all three properties are present: high-bandwidth communication, the need to build trust and rapport, and the need for everyone to be present at the same time. The speed of a decision should not be limited by the availability of the person with the busiest calendar.

Clear Agendas, Clear Outcomes, Clear Actions

A meeting agenda should be written before the event and shared with all attendees. The agenda should include purpose and talking points including ideal outcome.

Calendar Stagnation: Blowing It All Up

The author suggests resetting calendar at various points of the year and delete recurring meetings to make sure everyone is using their time wisely.

Syncs, Status Updates, and Other Ways to Die

The author offers alternatives to various types of meetings such as:

- Chat updates instead of standups.

- Weekly updates that is shared asynchronously instead of weekly group syncs.

- Enforce strict agenda for staff meetings that focus on critical issues the team is facing.

- Instead of unfacilitated brainstoring, consider getting participants to sketch ideas beforehand and share them asynchronously.

Auditing Your Time

In High Output Management, Andy Grove categorizes the activities of a senior manager into four buckets:

- Information gathering

- Decision-making

- Nudging

- Being a role model

4. The Games We Play and How to Win Them

This chapter focuses on fundamentals of managing senior people and other techniques for achieving goals.

Management 101: The Fundamentals

Coaching Versus Directing

Instead of directing managers and senior individual contributors, you will be coaching them. The author recommends GROW model that stands for:

- What is Goal?

- What is current Reality or situation?

- What are Obstacles?

- What are Options available?

- Way-forward for next steps, decisions and actions.

This model is similar coaching and can be used for directive coaching or following interests where you listen to them on what they should do.

Delegation

The essential principle of delegation is to assign the responsibility of a task to others while still retaining accountability for its completion and ensuring it meets the expected high standards. The key to effective delegation is to clearly define where you stand on the accountability scale, and to specify who is accountable and who is responsible for the task.

1:1s 101

1:1s is the backbone of your relationship with your direct reports and you should treat 1:1s with the utmost priority.

Contracting

The author suggests an exercise called contracting for effective 1:1s that asks questions such as:

- What are the areas that you would like support with?

- How would you like to receive feedback and support from me?

- What could be a challenge of us working together?

- How might we know if the support I’m offering isn’t going well?

- How confidential is the content of our meetings?

Focus and Format

The author recommends a clear focus and format for 1:1s by having a shared agenda, being mindful of time, using time to coach, summarizing and agreeing to next steps.

Brag Docs: The Greatest Gift You’ll Ever Receive

The brag docs track of what your direct reports are doing by maintaining a shared document that regularly updates their achievements, challenges, and goals. The author suggests structure for a bag doc such as choosing a period of time, broad goals, link achievements to wider goals, and review it regularly.

It’s All Just Leadership After All

The author recommends using same strategy for managing senior managers and senior individual contributors.

Control at the Intersection

The author recommends delegation model to manage senior staff that report to you, regardless of their role. Senior individual contributors demonstrate leadership by leading technical initiatives such as leading a project or a technical area.

From the Swamp to Infinity: Achieving Together

The author recommends building relationship with your staff that leads working together towards the same goal.

The Swamp

Senior managers often face a constant influx of tasks, resulting in a reactionary and disorganized situation that the author refers to as “the swamp.” The author suggests a mental model to make sense of the issues as managers wade through the muddy water.

Finite and Infinite Games

The author suggests Finite and Infinite Games based on James Carse book.

- Finite games: These are games with a clear beginning and end. They follow a set of agreed-upon rules, and the objective is to win. Each game has an entry criteria or the problem to solve, rules or constraints, and exit criteria or the success. As a manager, you need to minimize number of active finite games to prevent context-switching and reducing entropy in the organization.

- Infinite games: These games have no defined start or finish. Players come and go, the rules constantly change, and the goal is to continue playing. Finite games can be played within infinite games, e.g., product roadmap may require finite games from engineering, sales, marketing and other organizations. Infinite games require maintaining stability to keep players happy, motivated, growing, learning, and, most importantly, preventing burnout.

5. Become a Great Engineering Leader

This chapter classifies the type of work for individual contributors so that senior managers benefit from a close relationship with individual contributors.

Individual Contributors: The Higher Rungs

As Senior Engineers advance in their careers, they can choose between the managerial track to become a manager or the technical track to become a Staff or Principal Engineer.

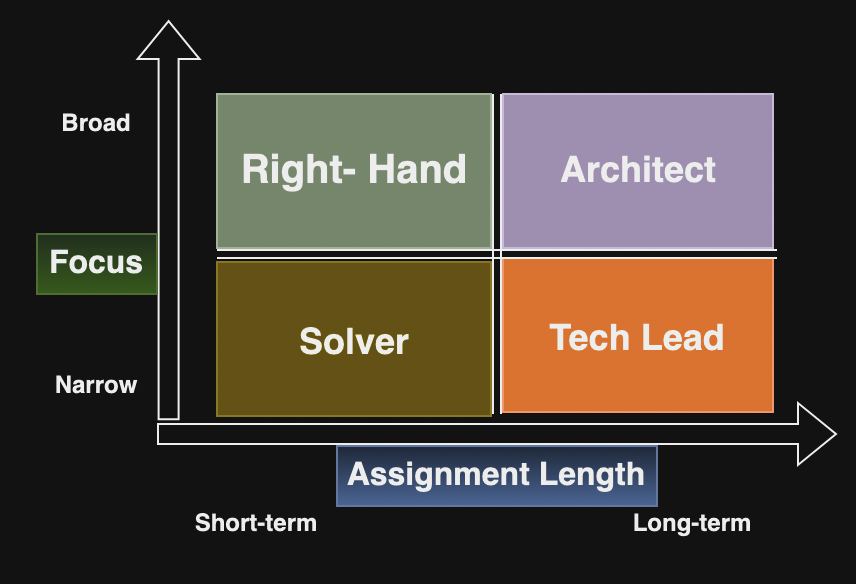

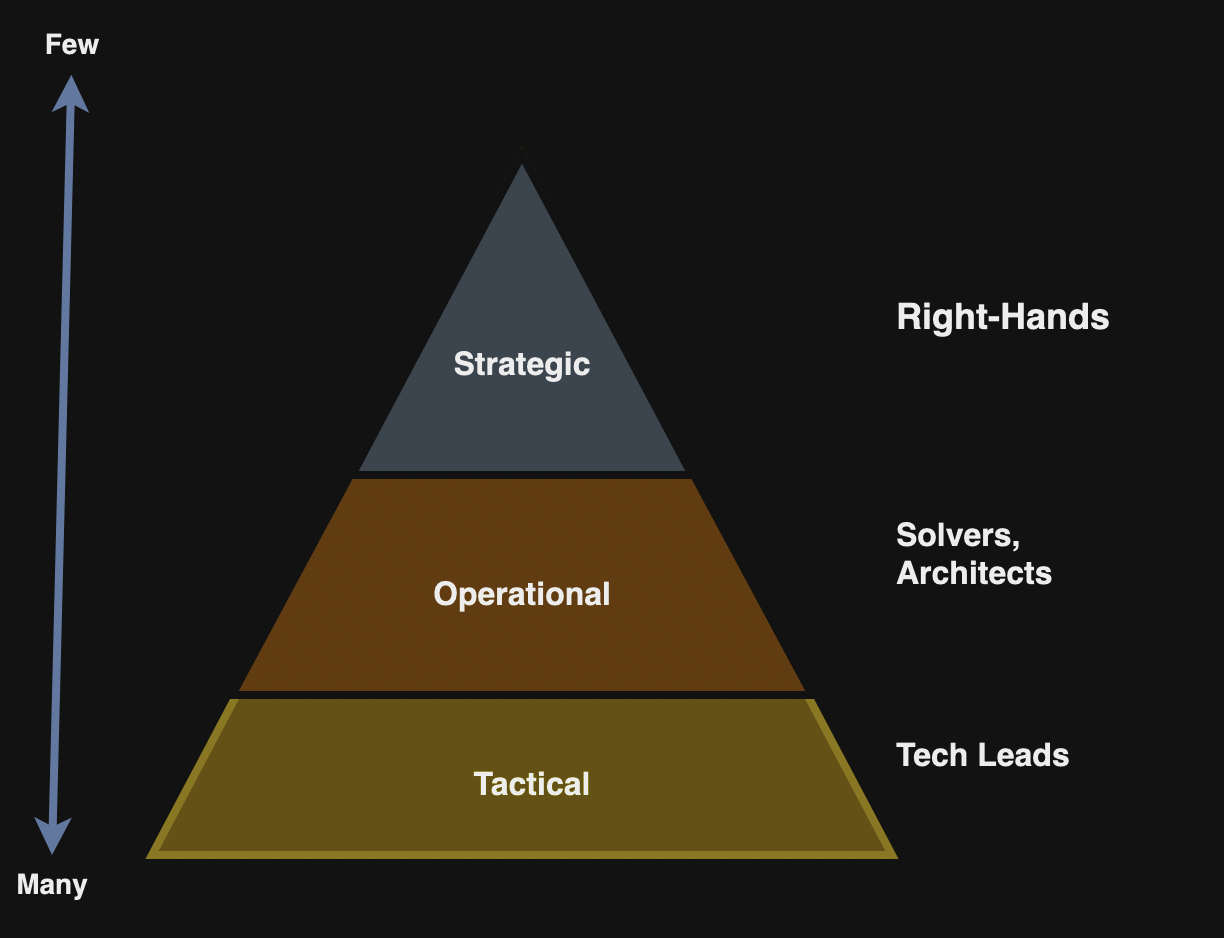

The Four Archetypes: Pieces of Your Puzzle

In Staff Engineer: Leadership beyond the management track, the author describes four archetypes of senior individual contributors:

- The Tech Lead who closely works with a single team.

- The Architect who is responsible for ongoing design, scalability and quality of the system.

- The Solver who solves complex issues.

- The Right-Hand who partners with a senior manager to increase their bandwidth.

Deploying Senior Individual Contributors

- The scope of Engineering Manager typically a single team and Tech Lead archetype fits for this role.

- The scope of Senior Engineering Manager is broader with multiple teams and it can deploy multiple archetypes such as the Tech Lead, the Solver and the Architect.

- At the Director and VP level, the Right-Hand archetype becomes a viable option typically Staff/Principal Engineer when reporting to the Directory and Distinguished Engineer when reporting to the VP.

The Technical Shadow Organization

The group of senior individual contributors forms a kind of technical shadow organization that influences and guides the work being done.

Your Technical Council

The Technical Council is a group of senior individual contributors who meet regularly to discuss and guide the organization’s technical direction. The Technical Council can be utilized to discuss and make decisions on various topics, including the technical roadmap, technical standards, technical debt, deep dives, and reviews.

Building Connections Across the Organization

The author encourages the Technical Council to establish connections across the organization to prevent knowledge silos and better serve the broader organization.

6. The Tragedy of the Common Leader

In this chapter, the author demonstrates how middle managers can combat entropy when they are continually reacting and receiving without reciprocation from others.

But We Didn’t Want This to Become a Dumpster Fire

The author introduces the tragedy of the commons, where individuals acting in their own self-interest deplete a shared resource, leading to complex shared codebases or infrastructure that no one wants to take ownership of. The tragedy of the commons opposes longtermism, the principle of selflessly investing in a shared future, even if it requires sacrificing in the present.

Up and Down but Not Sideways

The middle managers reporting to the common leader often look up and down the org chart but not sideways. Protecting your team while competing for the manager’s time, focus, and favor can create a hostile and competitive environment.

Magnetism and Polarity: Pulling Peers Together

The author suggests strengthening relationships with peers to achieve collective goals. By connecting with peers, both you and your peers can gain valuable benefits from the relationship.

Attraction, Repulsion, and the Middle Ground

The author introduces a concept of polarity similar to magnets, where positive polarity creates value for other teams by attracting, negative polarity creates conflict by repelling, and neutral polarity creates neither value nor conflict for other teams.

Polarity-Led Relationships

The author defines following relationship traits based on polarity:

- Positive: Your team enables or collaborates with the other team. You can share knowledge and focus on ways to improve collaboration.

- Negative: You team has difficulty collaborating with the other team or your team’s direction collides with the other team strategically. You can build trust and empathy with the other team to improve the collaboration.

- Neutral: You team rarely interact with the other team. You can build trust and rapport with the other team.

Actually, It’s All on You: Do It Yourself

The author recommends proactively establishing connections with your peer group and continually nurturing them to demonstrate that you are a trusted partner and collaborator, helping to fight entropy of competing with manager’s time. To combat the tragedy of the commons, the author reiterates lessons from longtermism and infinite games, advocating for a positive-sum game instead of a zero-sum game.

Your Manager Is Not Your Single Point of Contact

In some organizations a set of peers only communicate with each other through their manager who becomes a bottleneck. This is an antipattern that encourages a lack of transparency, politics and snide behavior. Instead, the author recommends fostering open communication among peer groups through a chat channel, regular meetings, and seeking discussions proactively.

The Best Way to Build Trust: Deliver Something Awesome

Some peer groups may be quick to spot and escalate problems but rarely take action to fix them. The author recommends dedicating 10 percent of your capacity to initiatives that improve the organization such as codifying best practices, and unifying reporting on health of the code and production environment.

7. Of Clownfish and Anemone

This chapter focuses on developing a productive, symbiotic relationship with your manager.

Teenage Rebellion: Raging Against the Machine

In a senior leadership role, you are expected to be self-sufficient and an expert in your domain, with a unique leadership style or perspective on the organization. This can sometimes lead to friction with your manager and disappointment when they don’t meet your standards.

The Reporting to Peter Principle

The Peter Principle states that “in a hierarchy every employee tends to rise to their level of incompetence.” The author introduces the Reporting to Peter principle, which suggests that in every organization, you will eventually reach a point where you experience significant internal conflict with how your manager performs their job. The author recommends embracing these differences, viewing them as strengths, and using them as opportunities to learn from each other and develop a symbiotic relationship.

Prescriptions Don’t Work: Tools Do

The author advises against relying on prescriptive advice. Instead, they suggest observing and understanding both your own strengths and weaknesses, as well as those of your manager, and using this insight to build a mutually beneficial relationship.

Symbiosis: Defined, Observed, and Applied

The author recommends recognizing additive and subtractive actions and cultivating symbiotic relationships with your manager that benefit both parties.

Skip to the End: Defining the Relationship

The author distinguishes between additive and subtractive actions in relationships:

- Additive actions: These explicitly benefit your relationships and can be undertaken by both parties.

- Subtractive actions: These can cause friction in your relationship and should be transformed into additive actions.

To build a mutually beneficial virtuous cycle, the author recommends transforming subtractive actions into additive ones. For example, if regular one-on-one meetings are frequently cancelled at the last minute (a subtractive action), this can be transformed into an additive action by implementing weekly written status updates.

How Do You Actually Want to Be Managed?

As a high-growth individual, you may desire more autonomy than your manager is comfortable giving, or, particularly at senior levels, you might want more frequent check-ins than your manager provides. The key to resolving this misalignment is self-awareness: understand your preferred working style, clearly communicate your expectations to your manager, and work together to find a mutually satisfactory arrangement.

When the Stuff Hits the Fan

This section addresses how to handle adverse situations, including escalations, intense scrutiny (the “eye of Sauron”), and unexpected negative events.

Escalations

Well-managed escalations can be highly productive, fostering trust among you, your manager, and other involved parties, while leading to improved outcomes for the entire organization. The author provides following recipe for dealing with escalations:

- Identify the problem.

- Have all parties involved in the escalation agree to it being escalated.

- Collaborate with all involved parties to identify the problem, explore potential solutions, and evaluate the trade-offs of each option.

- Make a recommendation.

- Escalate!

- Don’t take it personally.

The Eye of Sauron

The Eye of Sauron refers to situations involving external events or intense internal scrutiny, often triggered by a major incident, a sudden increase in oversight, or a change in direction from an executive. The author offers following recipe for handling the Eye of Sauron:

- Remain calm.

- Listen to all inputs.

- Come up with a communication plan.

- Coach others to see these situations as a learning opportunity.

- Retrospect after the situation is over.

Unpleasant Surprises

Unpleasant surprises are situations that catch both you and your manager off guard. The author offers following recipe for handling unpleasant surprises:

- Assess and confirm the situation.

- Come up with a clear plan.

- Execute on the plan.

- Retrospect after the situation is over.

8. Trifectas, Multifectas, and Allies

This chapter explores trifectas (three people from different disciplines collaborating), multifectas (teams with more than three disciplines), and allies (supportive individuals from other disciplines).

Omne Trium Perfectum

The author asserts that the number three frequently appears, as in the iron triangle where decisions has three options: scope, resources, and time, allowing for only two out of the three. Having three variables creates the ideal amount of tension for decision-making.

Trifectas: Your Own Perfect Triplet

A trifecta is a team of three individuals from different disciplines collaborating to achieve a goal, typically involving engineering, product, and UX. Different parts of the department may have varied trifecta members. For instance, a platform team might include engineering, product, and developer relations instead. The author outlines the following responsibilities for a team’s trifecta:

- Ensure strategic alignment.

- Define the team’s roadmap.

- Make decisions.

- Drive up the execution of their individual crafts.

- Resolve escalations and blockers.

- Communicate with stakeholders.

Trifectas Should Go All the Way Up

Many organizations structure their reporting lines by discipline, causing trifectas to disappear and resulting in dysfunctional behaviors like lack of visibility, accountability, and clear escalation paths. The author recommends maintaining a trifecta organizational structure independent of reporting lines to ensure clear accountability, quick resolution of escalations, and alignment with the roadmap and project approvals.

Setting the Stage for Your Trifecta

The author offers following tips for a healthy trifecta relationship:

- Start a private chat channel.

- Consider a regular meeting.

- Consider office hours or regular syncs with front-line trifectas.

- Develop a process for project approvals.

- Develop a process for reporting on progress.

Extending to Multifectas

Bringing a new feature to market requires more than just a trifecta; it involves additional stakeholders such as marketing, sales, support, developer relations, legal, and security. These groups form a multifecta that can be organized for sustained collaboration.

Snow Melts at the Periphery

In High Output Management, Andy Grove wrote that “the snow melts at the periphery first.” The author recommends a concerted effort to be connected to outside world where you allies come in. When identifying your allies, author recommends forming a symbiotic relationship by sharing useful information, engaging with customers, resolving issues, and providing coaching.

9. Communication at Scale

This chapter focuses on large-scale communication, communication patterns, and building a communication architecture.

Standing on the Shoulders of Scribbles

In this section, the author emphasizes the role of communication in enabling organizational progress and learning.

Patterns of Communication

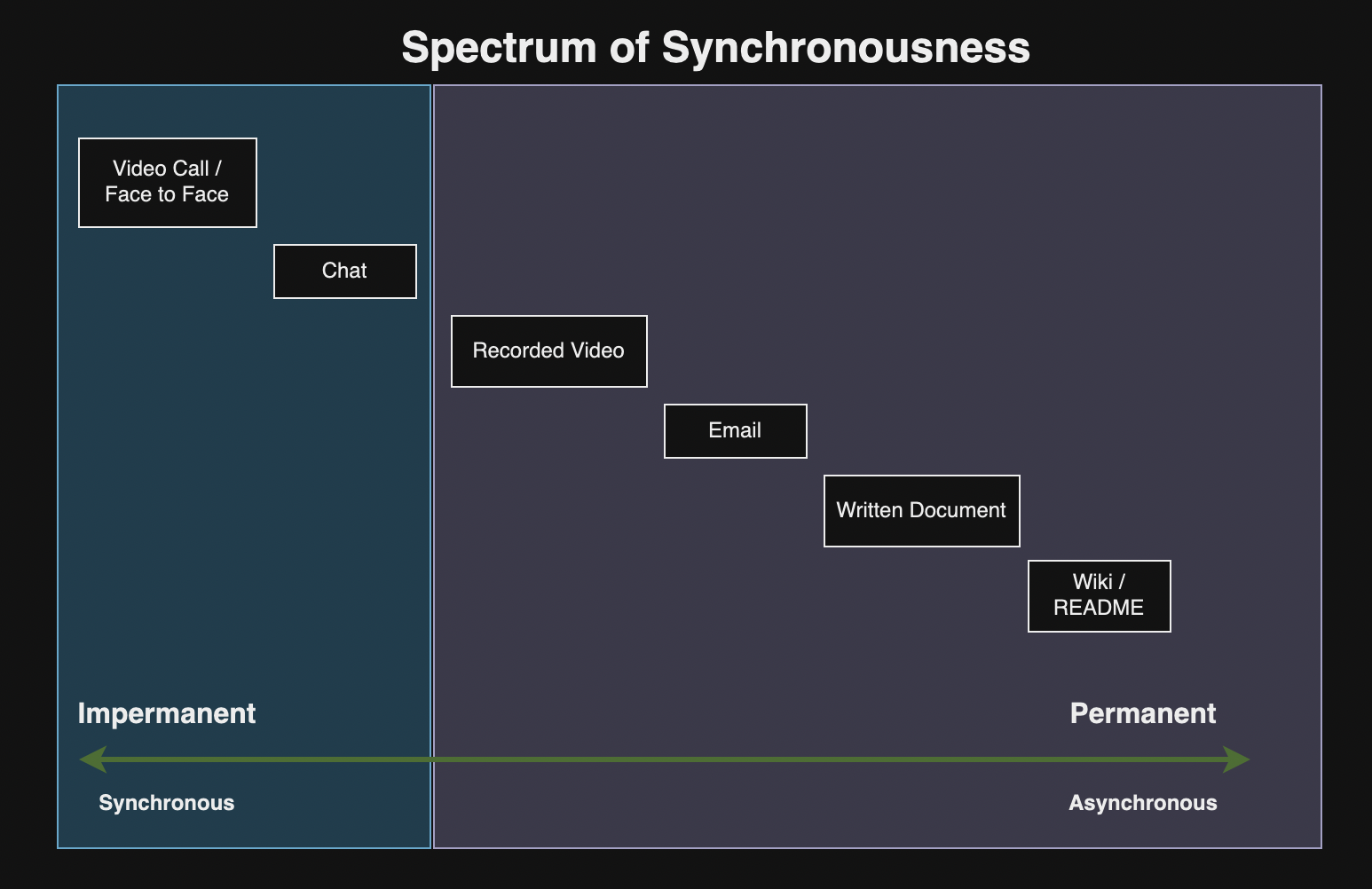

The author defines following patterns of communication:

- Synchronous versus asynchronous

- Stateless versus stateful

- One-to-one, one-to-many, many-to-many

The Spectrum of Synchronousness

As you advance in seniority and your organization grows, efficient synchronous communication becomes more challenging so you have rely on asynchronous communication.

Artifacts: One-to-One, One-to-Many, Many-to-Many

When designing data pipelines, you must consider the relationships between data sources, sinks, and the transformations in between. The author recommends similar scrutiny for senior leaders for the design of communication so that communication artifacts (documents, emails, meeting notes) support organizational learning and progress. Moving these ideas from transient, informal thoughts to formal, documented communication ensures they contribute to lasting organizational success.

Optimizing for Decision Speed

Creating shareable and permanent artifacts is a great start, but the ultimate goal is to facilitate decision-making. As a leader, you should focus on optimizing decision speed without compromising decision quality and distinguish between:

- One-way doors: Irreversible decisions, like making breaking changes to an API or firing an employee require careful consideration and often higher-level approval.

- Two-way doors: Reversible decisions, like choosing a temporary UI component that can be made quickly and adjusted later if needed.

The author describes following protocol when making decisions:

- Identify the type of decision (one-way or two-way).

- Make two-way door decisions as close to the front line as possible and empowering teams to decide autonomously.

- Escalate one-way door decisions to the appropriate level to ensure critical decisions have top-level buy-in.

Following this protocol allows 90% of decisions to be made quickly and safely, while the remaining 10% receive the necessary scrutiny, balancing speed and careful consideration.

Parkinson’s Law: It’s Real, So Use It

Parkinson’s Law states that “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.” Without deadlines, projects often take longer and suffer from feature creep and scope bloat. The author recommends setting challenging deadlines to achieve better results by managing the Iron Triangle of scope, resources, and time. Additionally, implementing a weekly reporting cadence helps maintain discipline and energy.

Leadership Is Writing

Much of leadership involves writing and as you advance in seniority, you will spend an increasing amount of time reading and writing.

The Paper Triangle

Writing is the most efficient way to communicate complex ideas to other people.

Writing is the most efficient way to communicate complex ideas, as reading is faster than listening. Writing is also the process of thinking itself and aids in organizing and structuring thoughts. The author recommends following steps to communicate effectively:

- Write to think: Jot down thoughts without worrying about clarity.

- Interrogate your thoughts: Review and question your initial writing to identify gaps.

- Edit to read: Refine the text for clarity and conciseness for others.

This process, akin to the Iron Triangle of scope, resources, and time, ensures clear communication and aids in organizational progress.

What Is Your Recommendation?

The author recommends guiding conversations with clear recommendations rather than strong opinion, loosely held when making decisions. When reviewing documents or discussing problems, always start with a recommendation so that it fosters a culture where every communication aims to move the organization forward.

Building Your Second Brain

As writing helps organizing thoughts, the author recommends creating personal artifacts besides creating artifacts for others. At higher organizational levels, dealing with vast information is routine and the concept of a “second brain” can be beneficial in managing information. A second brain is an interconnected system to capture, process, and recall information. Popular tools include Roam Research, Notion, Obsidian, and Logseq for creating and linking notes, forming a knowledge graph. The author offers following recipe for starting with a second brain:

- Create a Daily Note.

- Link Important Concepts.

- Use Proactively as a Reference.

- Regularly Review Your Knowledge Graph.

The Grand Commit Log of History

The organization’s state can be viewed as a function of past ideas, decisions, and actions, forming a “commit log of history.” This section looks at the communication architecture framework based on tactical, operational and strategic level.

The Tactical Level

At the tactical level (frontline teams), key elements include:

- Codebase artifacts include:

- Good commit messages

- Architecture Decision Records (ADRs)

- Documentation

- Projects: Each team should have:

- A project container such as Github or JIRA project.

- Statuses for their projects.

- Design documents

- Regular updates

- Communication: Each team should have:

- A private team chat

- A public team chat

- An announcement mechanism

- Metrics: Each team should have:

- Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

- Operational health metrics

- Logs of incidents and post-mortems

- Meetings: a variety of meetings that they attend

At the operational level

At the operational level (director level), key elements include:

- Communication: Each operational grouping should have:

- An optional private department chat

- A public department chat

- Discipline-specific private chats such as engineering managers or product mangers

- An internal announcement mechanism

- An external announcement mechanism

- Projects: Each operational grouping should have:

- Rollup dashboards

- Clearly visible statuses

- Approval information

- Metrics: Each operational grouping should have:

- Department KPIs

- Operational health metrics

- Rollup of incidents and post-mortems

- Meetings: Each operational grouping should have:

- A regular all-hands

- Office hours

- Project syncs

At the strategic level:

At the strategic level (executive level), key elements include:

- Communication:

- Ownership of the system of truth, deciding what tools are used.

- The vision

- The mission

- Discipline leadership chats

- Projects:

- High-level dashboards

- Flags for projects that are at risk

- Metrics:

- Company or Department-wide KPIs

- Budgets and forecasts

- Rollup of high-critical issues

- Meetings:

- Town halls

- Regular business reviews

- Project syncs

- Board or investor interactions

10. Performance Management: Raising the Bar

This chapter examines the overarching concepts of performance management and explores the calibration process to ensure fairness and consistency in evaluations.

The Rising Tide: Why We’re Doing This

The goal of performance management is to improve everyone in the organization and keep raising the bar. Key elements of a good performance management system includes:

- A well-defined set of competencies that outlines expectations for all employees.

- A regular performance review process.

- A calibration process.

- A PIP process.

- A compensation process

Performance Management of Senior Staff

In High Output Management, Andy Grove describes the output of a manager as being the output of their organization plus the output of the neighboring organizations under their influence. This output can be measured by:

- Self-assessment: Subjective, Qualitative (self-awareness about their impact), Quantitative.

- 360 feedback: Negative, Neutral, Positive.

- Metrics or KPIs: Defined, Progressed for the period, Achieved or Exceeded.

- Your own observations: Negative, Neutral, Positive.

The author recommends starting a brag doc, mentoring, and writing a monthly detailed update for their area.

Calibrations: Converging on Fairness

Calibration is typically run by HR and ensures that performance management is fair and consistent across the entire organization. It can be broken into three phases:

- Preparation: Generates all of the supporting evidence for each person.

- Calibration: Reviews the aggregate performance of staff in the organization.

- Actions: Such as follow-ups with managers.

Debugging Common Performance Management Issues

- Your Lowest Performer Is the Performance Bar You Accept

- Current Performance Is Not Historical Performance

- Brilliant Jerks Are Not Worth It

- Keeping job title inflation under control is extremely important

- Being Held Hostage

- Gather Data When You Disagree With One of Your Managers

11. Strategy 101

This is first chapter for third part of the book that focuses on strategy, planning and execution. It defines a strategy and focus on engineering strategies.

What on Earth Is a Strategy, Anyway?

A strategy encompasses the initiatives an organization undertakes to create value for itself and its stakeholders while gaining a competitive market advantage. It defines the specific approaches the organization will employ to position itself so that it can achieve both short-term and long-term objectives.

A Strategy Is Not a Plan

Professor Roger Martin defines strategy as “an integrative set of choices that positions you on a preferred playing field in a way that enables you to win.” Martin notes that leaders often default to planning instead of strategizing because it’s easier. This tendency stems from two factors:

- Strategy focuses on outcome such as acquiring and satisfying customers, who are external to the organization.

- Planning deals with internal resources and costs, which are controllable, and where the organization itself is the customer.

Engineering Strategy: Your Piece of the Puzzle

The engineering strategy is a vital subset of the overall company strategy but companies often lack a well-documented and communicated engineering strategy. As an engineering leader, you navigate two distinct worlds: the nontechnical senior executives who struggle to understand engineering complexities and the engineers who seek clarity on how their work aligns with the company’s goals. Balancing these needs is challenging, but a well-crafted strategy will address both groups effectively.

Let’s Build an Engineering Strategy Together

The author breaks down strategy into four parts:

- Initiatives – What are we hoping to achieve and why?

- Success metrics

- Investments in teams and technology

- Processes and ways of working

12. Company Cycles

This chapter looks at the calendar and how the year is broken up into cycles that serve as the rhythm of the business.

The Calendar Is Dead, Long Live the Calendar

Regardless of the estimation framework used by engineering, it must ultimately translate into concrete commitments that the entire organization can use for accountability.

Different Departments, Different Cycles

Typically, departments divide the year into four quarters (Q1..Q4). As a senior leader, you need to align your efforts effectively with the broader business cycles. You need to balance continuous delivery with the ability to support major launches or unveilings. Effective communication with the rest of the business is key to translate your team’s work into terms that make sense to other departments. The author recommends increasing the awareness of financial cycles so that you can understand and justify your spending.

Sales: Can’t Live With Them, Can’t Live Without Them

In order to support the sales team, a senior leader must generate certainty about future developments, provide support to the sales team and handle urgent customer demands.

Removing Uncertainty: The Tip of the Iceberg

The engineering leadership as being about managing and reducing uncertainty as building large scale software often involves complex tasks that others may not be visible like building an infrastructure. In order to shift your team’s focus from deadlines to reducing uncertainty, you must prototype, design, code and ship incrementally. You must prioritize tackling the most uncertain aspects first to either validate their feasibility or explore alternative solutions. The author recommends incorporating following:

- Defining success metrics and key performance indicators upfront.

- Prototyping to validate ideas quickly and efficiently.

- Creating technical design documents to refine approaches before coding begins.

Structuring a Roadmap Based on Uncertainty

As uncertainty in a project decreases over time, you can structure your roadmap to reflect this progression. In business cycles, you can:

- Be certain about the next month

- Be fairly certain about the next quarter

- Be less certain about the next half-year

- Be even less certain about the next yea

Your roadmap should include:

- Feature

- Stage such as Rollout, Build, Prototype, Design

- Expected delivery date or quarter

- Initiative with links to relevant strategy documents

- Owner

- Latest update

- Latest demo

- Dependencies

Marketing: Big Bangs Without the Bang

The author recommends following to ensure alignment between marketing and engineering:

- Clear Roadmap

- Feature Flags

Feature flags offer several benefits:

- Continuous Delivery

- Early Testing

- Simplified Testing

- Easy Rollbacks

- Internal Visibility

- A/B Testing

- Beta Programs

- Early Access

Two Worlds Collide: Troubleshooting and Solutions

Misselling: The Tail Wagging the Dog

One of the most common frustrations arises when salespeople sell products or features that don’t yet exist. To address this, the author offers the following advice:

- Understand how this happens in the first place.

- Build better connections at the periphery and at the top of sales.

- Set aside resource allocation for these surprises.

- Make it clear what suffers as a result of reprioritization.

No Feature, No Deal

The ideal roadmap focuses on features that enhance the product for a broad audience, saying “no” more often than “yes.” The author cautions against building niche features for a few customers, as this can dilute your product’s vision, clutter your roadmap, and create long-term maintenance challenges. Adding too many specialized features can lead to a “death by a thousand papercuts,” where minor adjustments accumulate into significant complications over time.

Full-On Feature Factory Grind

The engineering department may feel like a “feature factory,” constantly producing new features without addressing technical debt, resiliency, scalability, or developer efficiency. The author recommends allocating engineering resources wisely for long-term stability and performance. Here are some strategies:

- Educate the Business that speed and stability are features

- Allocate Time for Engineering-Led Work

- Highlight the Cost of Neglect

- Celebrate Engineering Wins

Remember, They’re Smart Too

The author offers the following advice if there’s a pervasive culture where engineers believe they are smarter than the rest of the business:

- Be clear that this is unacceptable.

- Help your teams understand that transparency buys them more time to do engineering work.

- Be clear that the rest of the business is incredibly smart too.

13. Money Makes the World Go Round

This chapter covers the basics of company finance and managing a large budget.

Finance 101: The Basics of Company Finance

A company operates like a flywheel, where money (input) is converted into products and services (output) that generate more money than the cost to produce them. This process creates a self-sustaining cycle that drives growth. Each department functions as a subsystem, with the executive and finance teams allocating resources to maximize output. Expenditures fall into two categories: capital expenditure (capex) and operating expenditure (opex). In order to accelerate the company’s growth, the gap between revenue (top line) and profit (bottom line) should be maximized.

Modes of Operation: Bootstrapping, Venture Capital, and More

Startups have different ways to fund their growth such as:

- Bootstrapping

- Venture Capital

- Angel Investment

- Debt Financing

The funding method influences how a company operates and allocates resources.

Cost Centers and Profit Centers

A cost center is a department that incurs expenses but doesn’t directly generate revenue, like HR. A profit center generates revenue, such as the sales department. Engineering can be either a cost or profit center, depending on the company and even specific teams within it.

SaaS Jargon Busting: Acronym Soup

Author introduces key metrics for SaaS startups such as:

- MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue)

- ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue)

- LTV (Lifetime Value)

- CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost)

- LTV:CAC Ratio – profitability from customer acquisition (ratio of 3:1 or higher is considered strong)

- Churn Rate

Do You Need to Make a Profit?

Many fast-growing, venture capital-backed technology companies operate at a loss, prioritizing rapid market capture over immediate profitability. This rapid growth strategy can lead to substantial returns for investors when the company eventually goes public or is acquired.

Managing a Large Budget: Levers and Dials

The author defines following kinds of costs for engineering departments:

- People – largest cost where you have to solve a multivariate optimization problem around allocation with following criteria:

- Alignment with strategy

- Alignment with increasing the power curve of capabilities

- Alignment with the mode of operation

- Infrastructure – next largest cost

- Opex infrastructure

- Capex infrastructure

- Software and Hardware

- Essential

- Productivity gains

- Temporary services (contractors) – Opex

Rule of Thumb

- A useful rule of thumb for people is to track the revenue per employee.

- Software and Hardware Spend as a Percentage of Revenue.

- Temporary services – Estimate the cost of not using them.

Common Dilemmas: Patterns to Follow

Build Versus Buy

The trade-offs include:

- You can build it to your exact specifications but it will take time and effort to build.

- Up and running quickly but it costs money.

Dealing with Vendors: Never Trust the Book Price

- Always negotiate

- Consider contract length – the longer the contract, the better the deal

- Consider volume – the more you buy, the better the deal

- Consider competition

Top Line Versus Bottom Line: The Eternal Struggle

Budget management involves balancing top-line growth with bottom-line costs. Key metrics to track:

- Revenue per employee (should increase over time)

- Infrastructure spend as % of revenue (should decrease over time)

- Software and hardware spend as % of revenue (should decrease over time)

- Cost of distraction from top-line focus (minimize based on company phase)

14. Boom and Bust

This chapter covers the phenomenon of boom and bust cycles and categorizes the operations of a company along a scale.

Spend! Invest! Grow! Crash! Burn! Rebuild!

Technology companies thrive on innovation, which is inherently risky. Rapid growth is crucial for long-term success, fueled by investment capital and driven by network effects. This leads to two outcomes: success (continued growth, acquisition, or going public) or failure (downsizing or closure). These outcomes contribute to the industry’s boom-bust cycles, characterized by periods of rapid expansion and hiring alternating with widespread layoffs and company closures.

ZIRP, QE, and the Tech Industry

The author discusses key macroeconomic factors influencing tech industry boom and bust cycles:

- Quantitative easing (QE)

- Low interest rates (ZIRP – Zero Interest Rate Policy)

- Low inflation

Peacetime and Wartime: A Spectrum

In The Hard Thing About Hard Things, Ben Horowitz introduces the concepts of peacetime (boom periods) and wartime CEOs (survival). Understanding where a company stands on this spectrum helps leaders adopt the appropriate strategy to guide their organization effectively.

Concentric Circles of Trust

The author introduces a model of concentric circles of trust:

- Confidential – most sensitive information (NDA)

- Sensitive

- Open

Leading Through Peacetime: Invest, Spend, Grow

In peacetime, growth is the agenda, which is governed by following activities:

- Hiring, Onboarding, and Ramping Up – onboarding and contribution curve.

- Incubating New Products – ensure that there are clear tripwires for success and failure.

- Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) – technical due diligence, talent assessment, organizational fit

Leading Through Wartime: Cut, Save, Rebuild

In wartime, your company is focused primarily on survival.

- Reforecasting, Restrategizing, and Reorganizing

- Understand drivers such as revenue targets, funding, costs, product-market fit

- Enumerate options – hiring, auditing software and services, negotiating with vendors, layoffs

- Layoffs: The Worst Part Comes First

- Become a Great Engineering Leader

- Maximizes the chances of the department and company surviving

- Retains the best talent

- Complies with labor laws

- A Line in the Sand – all your efforts within the inner circles of trust are brought out into the open

15. Tarzan Swings from Vine to Vine

This chapter offers guidelines for steering your career using Tarzan method.

The Fallacy of the Straight Line

Focus on what you can control, and let go of what you can’t.

The Tarzan Method

The direct path to a lofty career goal, like becoming the CTO might not exist or be clear. Instead, think of your career like Tarzan swinging through the jungle—moving from one opportunity to the next, guided by instincts and a general sense of direction.

The Trajectory of Your Swing

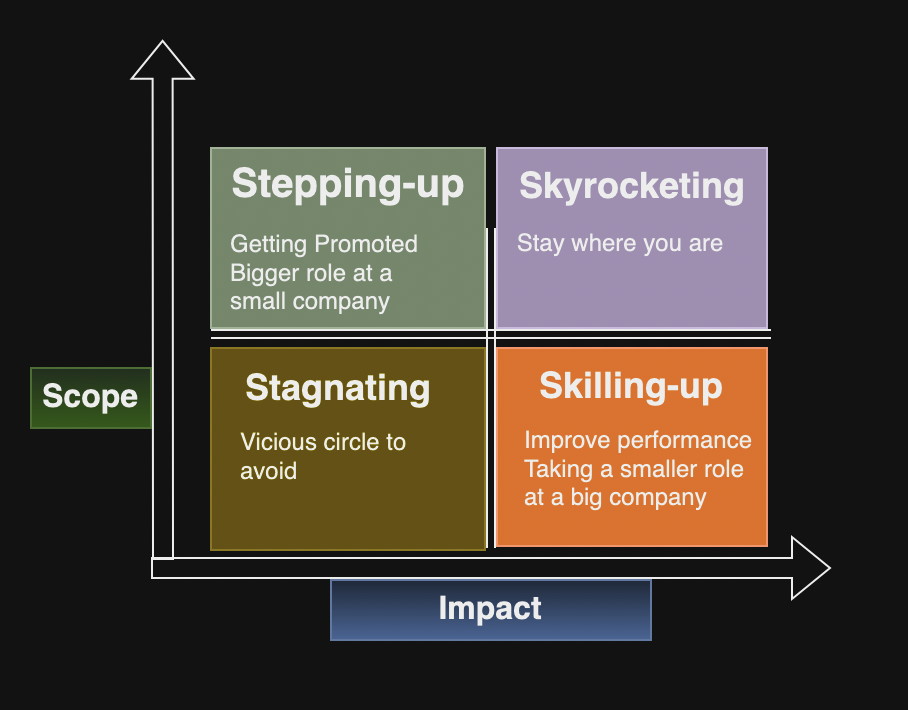

The author reiterates the concept of scope and impact:

- Scope refers to the breadth of responsibility, such as team size, budget, and influence.

- Impact refers to the depth of responsibility, such as the results of your work and the effectiveness of decisions.

Career growth can be visualized in a quadrant where:

- Stagnating (low scope, low impact) means being in an unchallenging role with little satisfaction

- Stepping Up (high scope, low impact) involves taking on more responsibility

- Skyrocketing (high scope, high impact) is the ideal state, often in a fast-growing startup

- Skilling Up (low scope, high impact) follows a period of stepping up, focusing on improving skills

Earn, Learn, or Quit

Y Combinator CEO Garry Tan suggests that “at every job, you should either learn or earn.” To progress in your career, it’s essential to consider how much you want to earn, what you want to learn, and how you can expand your scope and impact.

Putting It All Together

Writing Your Strategy

The author recommends answering the following questions:

- What kind of role might you see yourself in if you could achieve everything you wanted?

- What kind of environment do you want to work in?

- What sort of products or services is the company creating?

- What kind of people do you want to work with?

- What kind of impact do you want to have?

- What does all of the above mean for other aspects of your life?

The Next Vine Swing

The author recommends considering the following:

- Where are you right now in the quadrant?

- How long have you been in this quadrant?

- Is there a route to the top-right quadrant from where you are right now?

- At this moment, are you learning, earning, or both?

- What sort of opportunity would tempt you if it arrived tomorrow?