I’ve worked at organizations where engineers would sneak changes into production, bypassing CI/CD pipelines, hoping nobody would notice if something broke. I’ve also worked at places where engineers would openly discuss a failed experiment at standup and get help fixing it. The difference wasn’t the engineers—it was psychological safety. Research on psychological safety, particularly from high-stakes industries like healthcare, tells us something counterintuitive: teams with high psychological safety don’t have fewer incidents. They have better outcomes because people speak up about problems early.

Software engineering isn’t life-or-death medicine, but the principle holds: in blame cultures, I’ve watched talented engineers:

- Deploy sketchy changes outside normal hours to avoid oversight

- Ignore monitoring alerts, hoping they’re false positives

- Blame infrastructure, legacy code, or “the previous team” rather than examining their contributions

- Build elaborate workarounds instead of fixing root causes

These behaviors don’t just hurt morale—they actively degrade reliability. Post mortems in blame cultures become exercises in creative finger-pointing and CYA documentation.

In learning cultures, post mortems are gold mines of organizational knowledge. The rule of thumb I’ve seen work best: if you’re unsure whether something deserves a post mortem, write one anyway—at least internally. Not every post mortem needs wide distribution, and some (especially those with security implications) shouldn’t be shared externally. But the act of writing crystallizes learning.

The Real Problem: Post Mortem Theater

Here’s what nobody talks about: many organizations claim to value post mortems but treat them like bureaucratic checklists. I’ve seen hundreds of meticulously documented post mortems that somehow don’t prevent the same incidents from recurring. This is what I call “post mortem theater”—going through the motions without actual learning.

Shallow vs. Deep Analysis

Shallow analysis stops at the proximate cause:

- “The database connection pool was exhausted”

- “An engineer deployed buggy code”

- “A dependency had high latency”

Deep analysis asks uncomfortable questions:

- “Why don’t we load test with production-scale data? What makes it expensive to maintain realistic test environments?”

- “Why did code review and automated tests miss this? What’s our philosophy on preventing bugs vs. recovering quickly?”

- “Why do we tolerate single points of failure in our dependency chain? What would it take to build resilience?”

The difference between these approaches determines whether you’re learning or just documenting.

Narrow vs. Systemic Thinking

Narrow analysis fixes the immediate problem:

- Add monitoring for connection pool utilization

- Add a specific test case for the bug that escaped

- Increase timeout values for the slow dependency

Systemic analysis asks meta questions:

- “How do we systematically identify what we should be monitoring? Do we have a framework for this?”

- “What patterns in our testing gaps led to this escape? Are we missing categories of testing?”

- “What’s our philosophy on dependency management and resilience? Should we rethink our architecture?”

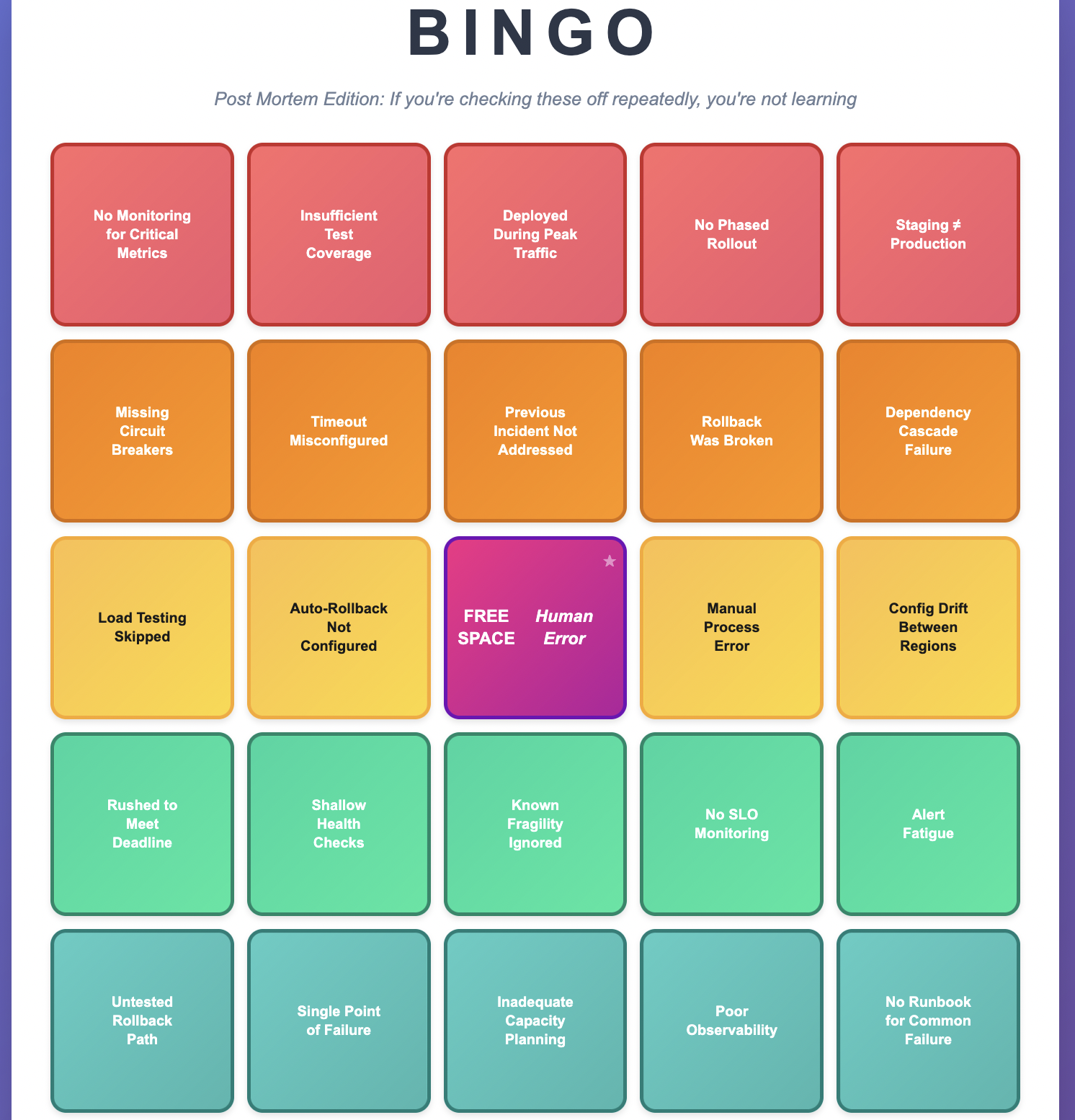

I’ve seen teams play post mortem bingo—hitting the same squares over and over. “No monitoring.” “Insufficient tests.” “Deployed during peak traffic.” “Rollback was broken.” When you see repeated patterns, you’re not learning from incidents—you’re collecting them. I have also written about common failures in distributed systems that can show up in recurring incidents if they are not properly addressed.

Understanding Complex System Failures

Modern systems fail in ways that defy simple “root cause” thinking. Consider a typical outage:

Surface story: Database connection pool exhausted

Deeper story:

- A code change increased query volume 10x

- Load testing used 1/10th production data and missed it

- Connection pool monitoring didn’t exist

- Alerts only monitored error rates, not resource utilization

- Manual approval processes delayed rollback by 15 minutes

- Staging environment configuration drifted from production

Which of these is the “root cause”? All of them. None of them individually would have caused an outage, but together they created a perfect storm. This is why I cringe when post mortems end with “human error” as the root cause. It’s not wrong—humans are involved in everything—but it’s useless. The question is: why was the error possible? What systemic changes make it impossible, or at least improbable?

You can think of this as the Swiss Cheese Model of failure: your system has multiple layers of defense (code review, testing, monitoring, gradual rollout, alerting, incident response). Each layer has holes. Most of the time, the holes don’t align and problems get caught. But occasionally, everything lines up perfectly and a problem slips through all layers. That’s your incident. This mental model is more useful than hunting for a single root cause because it focuses you on strengthening multiple layers of defense.

When to Write a Post Mortem

Always write one:

- Customer-facing service disruptions

- SLA/SLO breaches

- Security incidents (keep these separate, limited distribution)

- Complete service outages

- Incidents requiring emergency escalation or multiple teams

Strongly consider:

- Near-misses that made you think “we got lucky”

- Interesting edge cases with valuable lessons

- Internal issues that disrupted other teams

- Process breakdowns causing significant project delays

The litmus test: If you’re debating whether it needs a post mortem, write at least an internal one. The discipline of writing forces clarity of thinking.

Post Mortem Ownership

Who should own writing it? The post mortem belongs to the team that owns addressing the root cause, not necessarily the team that triggered the incident or resolved it. If root cause is initially unclear, it belongs with whoever is investigating. If investigation reveals the root cause lies elsewhere, reassign it.

The Anatomy of an Effective Post Mortem

Title and Summary: The Elevator Pitch

Your title should state the customer-facing problem, not the cause.

Good: “Users unable to complete checkout for 23 minutes in US-EAST”

Bad: “Connection pool exhaustion caused outage”

Your summary should work as a standalone email to leadership. Include:

- Brief service context (one sentence)

- Timeline with time zones

- Quantified customer impact

- How long it lasted (from first customer impact to full recovery)

- High-level cause

- How it was resolved

- Communication sent to customers (if applicable)

Timeline: The Narrative Spine

A good timeline tells the story of what happened, including system events and human decisions. Important: Your timeline should start with the first trigger that led to the problem (e.g., a deployment, a configuration change, a traffic spike), not just when your team got paged. The timeline should focus on the actual event start and end, not just your team’s perception of it.

All times PST 14:32 - Deployment begins in us-west-2 14:38 - Error rates spike to 15% 14:41 - Automated alerts fire 14:43 - On-call engineer begins investigation 14:47 - Customer support escalates: users reporting checkout failures 14:52 - Incident severity raised to SEV-1 15:03 - Root cause identified: connection pool exhaustion 15:07 - Rollback initiated 15:22 - Customer impact resolved, errors back to baseline

Key practices:

- Start with the root trigger, not when you were notified

- Consistent time zones throughout

- Bold major milestones and customer-facing events

- Include detection, escalation, and resolution times`

- No gaps longer than 10-15 minutes without explanation

- Use roles (“on-call engineer”) not names

- Include both what the system did and what people did

Metrics: Show, Don’t Just Tell

Visual evidence is crucial. Include graphs showing:

- Error rates during the incident

- The specific resource that failed (connections, CPU, memory)

- Business impact metrics (orders, logins, API calls)

- Comparison with normal operation

For complex incidents involving multiple services, include a simple architecture diagram showing the relevant components and their interactions. This helps readers understand the failure chain without needing deep knowledge of your system.

Make graphs comparable:

- Same time range across all graphs

- Label your axes with units (milliseconds, percentage, requests/second)

- Vertical lines marking key events

- Include context before and after the incident

- Embed actual screenshots, not just links that will break

Don’t do this:

- Include 20 graphs because you can

- Use different time zones between graphs

- Forget to explain what the graph shows and why it matters

Service Context and Glossary

If your service uses specialized terminology or acronyms, add a brief glossary section or spell out all acronyms on first use. Your post mortem should be readable by engineers from other teams. For complex incidents, consider including:

- Brief architecture overview (what are the key components?)

- Links to related items (monitoring dashboards, deployment records, related tickets)

- Key metrics definitions if not standard

Customer Impact: Get Specific

Never write “some customers were affected” or “significant impact.” Quantify everything:

Instead of: “Users experienced errors”

Write: “23,000 checkout attempts failed over 23 minutes, representing approximately $89,000 in failed transactions”

Instead of: “API latency increased”

Write: “P95 latency increased from 200ms to 3.2 seconds, affecting 15,000 API calls”

If you can’t get exact numbers, explain why and provide estimates with clear caveats.

Root Cause Analysis: Going Deeper

Use numbered lists (not bullets) for your Five Whys so people can easily reference them in discussions (“Why #4 seems incomplete…”). Use the Five Whys technique, but don’t stop at five if you need more. Start with the customer-facing problem and keep asking why:

1. Why did customers see checkout errors? -> Application servers returned 500 errors 2. Why did application servers return 500 errors? -> They couldn't connect to the database 3. Why couldn't they connect? -> Connection pool was exhausted 4. Why was the pool exhausted? -> New code made 10x more queries per request 5. Why didn't we catch this in testing? -> Staging uses 1/10th production data 6. Why is staging data volume so different? -> We haven't prioritized staging environment investment

Branch your analysis for multiple contributing factors. Number your branches (1.1, 1.2, etc.) to maintain traceability:

Primary Chain (1.x): Why did customers see checkout errors? did customers see checkou Application servers returned 500 errors [...] Branch A - Detection (2.x): Why did detection take 12 minutes? -> We only monitor error rates, not resource utilization Why don't we monitor resource utilization? -> We haven't established a framework for what to monitor Branch B - Mitigation (3.x): Why did rollback take 15 minutes after identifying the cause? -> Manual approval was required for production rollbacks Why is manual approval required during emergencies? -> Our process doesn't distinguish between routine and emergency changes

Never stop at:

- “Human error”

- “Process failure”

- “Legacy system”

Keep asking why until you reach actionable systemic changes.

Incident Response Analysis

This section examines how you handled the crisis during the incident, not how to prevent it. This is distinct from post-incident analysis (root causing) which happens after. Focus on the temporal sequence of events:

- Detection: How did you discover the problem? Automated alerts, customer reports, accidental discovery? How could you have detected it sooner?

- Diagnosis: How long from “something’s wrong” to “we know what’s wrong”? What information or tools would have accelerated diagnosis?

- Mitigation: How long from diagnosis to resolution? What would have made recovery faster?

- Blast Radius: What percentage of customers/systems were affected? How could you have reduced the blast radius? Consider:

- Would cellular architecture have isolated the failure?

- Could gradual rollout have limited impact?

- Did failure cascade to dependent systems unnecessarily?

- Would circuit breakers have prevented cascade?

For each phase, ask: “How could we have cut this time in half?” And for blast radius: “How could we have cut the affected population in half?”

Post-Incident Analysis vs Real-Time Response

Be clear about the temporal distinction in your post mortem:

- Incident Response Analysis = What happened DURING the incident

- How we detected, diagnosed, and mitigated

- Time-critical decisions under pressure

- Effectiveness of runbooks and procedures

- Post-Incident Analysis = What happened AFTER to understand root cause

- How we diagnosed the underlying cause

- What investigation techniques we used

- How long root cause analysis took

This distinction matters because improvements differ: incident response improvements help you recover faster from any incident; post-incident improvements help you understand failures more quickly.

Lessons Learned: Universal Insights

Number your lessons learned (not bullets) so they can be easily referenced and linked to action items. Lessons should be broadly applicable beyond your specific incident:

1. Bad lesson learned: “We need connection pool monitoring”

Good lesson learned: “Services should monitor resource utilization for all constrained resources, not just error rates”

2. Bad lesson learned: “Load testing failed to catch this”

Good lesson learned: “Test environments that don’t reflect production characteristics will systematically miss production-specific issues”

Connect each lesson to specific action items by number reference (e.g., “Lesson #2 ? Action Items #5, #6”).

Action Items: Making Change Happen

This is where post mortems prove their value. Number your action items and explicitly link them to the lessons learned they address. Every action item needs:

- Clear description: Not “improve monitoring” but “Add CloudWatch alarms for RDS connection pool utilization with thresholds at 75% (warning) and 90% (critical)”

- Specific owner: A person’s name, not a team name

- Realistic deadline: Most should complete within 45 days

- Priority level:

- High for root cause fixes and issues that directly caused customer impact

- Medium for improvements to detection/mitigation

- Low for nice-to-have improvements

- Link to lesson learned: “Addresses Lesson #2”

- Avoid action items that start with “investigate.” That’s not an action item—it’s procrastination. Do the investigation during the post mortem process and commit to specific changes.

Note: Your lessons learned should be universal principles that other teams could apply. Your action items should be specific changes your team will make. If your lessons learned just restate your action items, you’re missing the bigger picture.

Common Patterns That Indicate Shallow Learning

When you see the same issues appearing in multiple post mortems, you have a systemic problem:

- Repeated monitoring gaps -> You don’t have a framework for determining what to monitor

- Repeated test coverage issues -> Your testing philosophy or practices need examination

- Repeated “worked in staging, failed in prod” -> Your staging environment strategy is flawed

- Repeated manual process errors -> You’re over-relying on human perfection

- Repeated deployment-related incidents -> Your deployment pipeline needs investment

These patterns are your organization’s immune system telling you something. Listen to it.

Common Pitfalls

After reading hundreds of post mortems, here are the traps I see teams fall into:

- Writing for Insiders Only: Your post mortem should be readable by someone from another team. Explain your system’s architecture briefly, spell out acronyms, and assume your reader is smart but unfamiliar with your specific service.

- Action Items That Start with “Investigate”: “Investigate better monitoring” is not an action item – it’s a placeholder for thinking you haven’t done yet. During the post mortem process, do the investigation and commit to specific changes.

- Stopping at “Human Error”: If your Five Whys ends with “the engineer made a mistake,” you haven’t gone deep enough. Why was that mistake possible? What system changes would prevent it?

- The Boil-the-Ocean Action Plan: Post mortems aren’t the place for your three-year architecture wish list. Focus on targeted improvements that directly address the incident’s causes and can be completed within a few months.

Ownership and Follow-Through

Here’s something that separates good teams from great ones: they actually complete their post mortem action items.

- Assign clear ownership: Every action item needs a specific person (not a team) responsible for completion. That person might delegate the work, but they own the outcome.

- Set realistic deadlines: Most action items should be completed within 45 days. If something will take longer, either break it down or put it in your regular backlog instead.

- Track relentlessly: Use whatever task tracking system your team prefers, but make action item completion visible. Review progress in your regular team meetings.

- Close the loop: When action items are complete, update the post mortem with links to the changes made. Future readers (including future you) will thank you.

Making Post Mortems Part of Your Culture

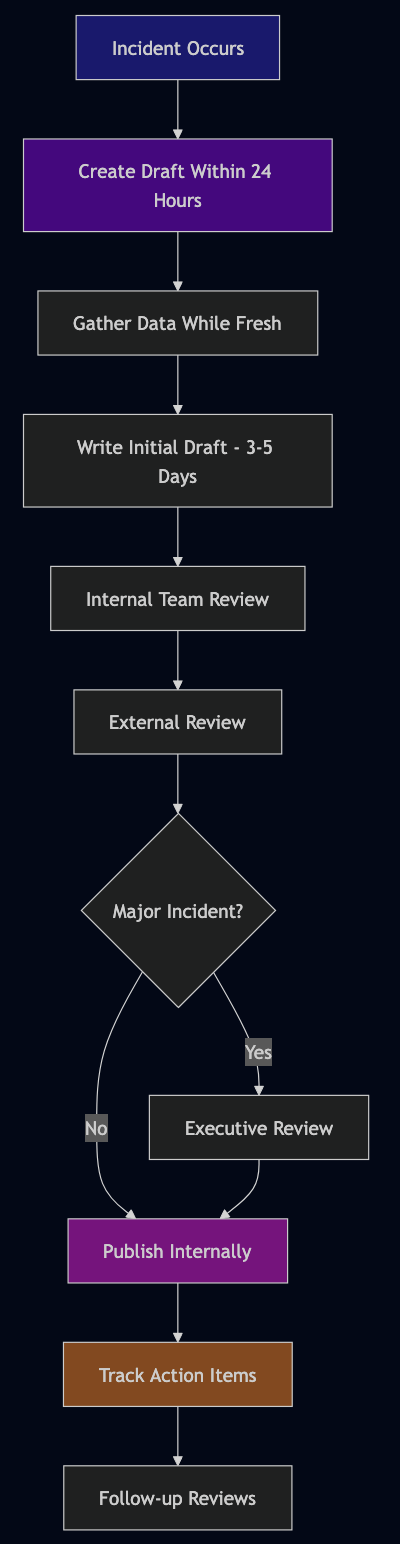

- Write them quickly: Create the draft within 24 hours while memory is fresh. Complete the full post mortem within 14 days.

- Get outside review (critical step): An experienced engineer from another team—sometimes called a “Bar Raiser”—should review for quality before you publish. The reviewer should check:

- Would someone from another team understand and learn from this?

- Are the lessons learned actually actionable?

- Did you dig deep enough in your root cause analysis?

- Are your action items specific and owned?

- Does the incident response analysis identify concrete improvements?

- Draft status: Keep the post mortem in draft/review status for at least 24 hours to gather feedback from stakeholders. Account for holidays and time zones for distributed teams.

- Make them visible: Share widely (except security-sensitive ones) so other teams learn from your mistakes.

- Customer communication: For customer-facing incidents, document what communication was sent:

- Status page updates

- Support team briefings

- Proactive customer notifications

- Post-incident follow-up

- Track action items relentlessly: Use whatever task system you have. Review progress in regular meetings.

- Review for patterns: Monthly or quarterly, look across all post mortems for systemic issues.

- Celebrate learning: In team meetings, highlight interesting insights from post mortems. Make clear that thorough post mortems are valued, not punishment.

- Train your people: Writing good post mortems is a skill. Share examples of excellent ones and give feedback.

Security-Sensitive Post Mortems

Some incidents involve security implications, sensitive customer data, or information that shouldn’t be widely shared. These still need documentation, but with appropriate access controls:

- Create a separate, access-controlled version

- Document what happened and how to prevent it

- Share lessons learned (without sensitive details) more broadly

- Work with your security team on appropriate distribution

The learning is still valuable—it just needs careful handling.

The Long Game

Post mortems are how organizations build institutional memory. They’re how you avoid becoming that team that keeps making the same mistakes. They’re how you onboard new engineers to the reality of your systems. Most importantly, they’re how you shift from a culture of blame to a culture of learning.

When your next incident happens—and it will—remember you’re not just fixing a problem. You’re gathering intelligence about how your system really behaves under stress. You’re building your team’s capability to handle whatever comes next. Write the post mortem you wish you’d had during the incident. Be honest about what went wrong. Be specific about what you’ll change. Be generous in sharing what you learned.

Your future self, your teammates, and your customers will all benefit from it. And remember: if you’re not sure whether something deserves a post mortem, write one anyway. The discipline of analysis is never wasted.