Introduction

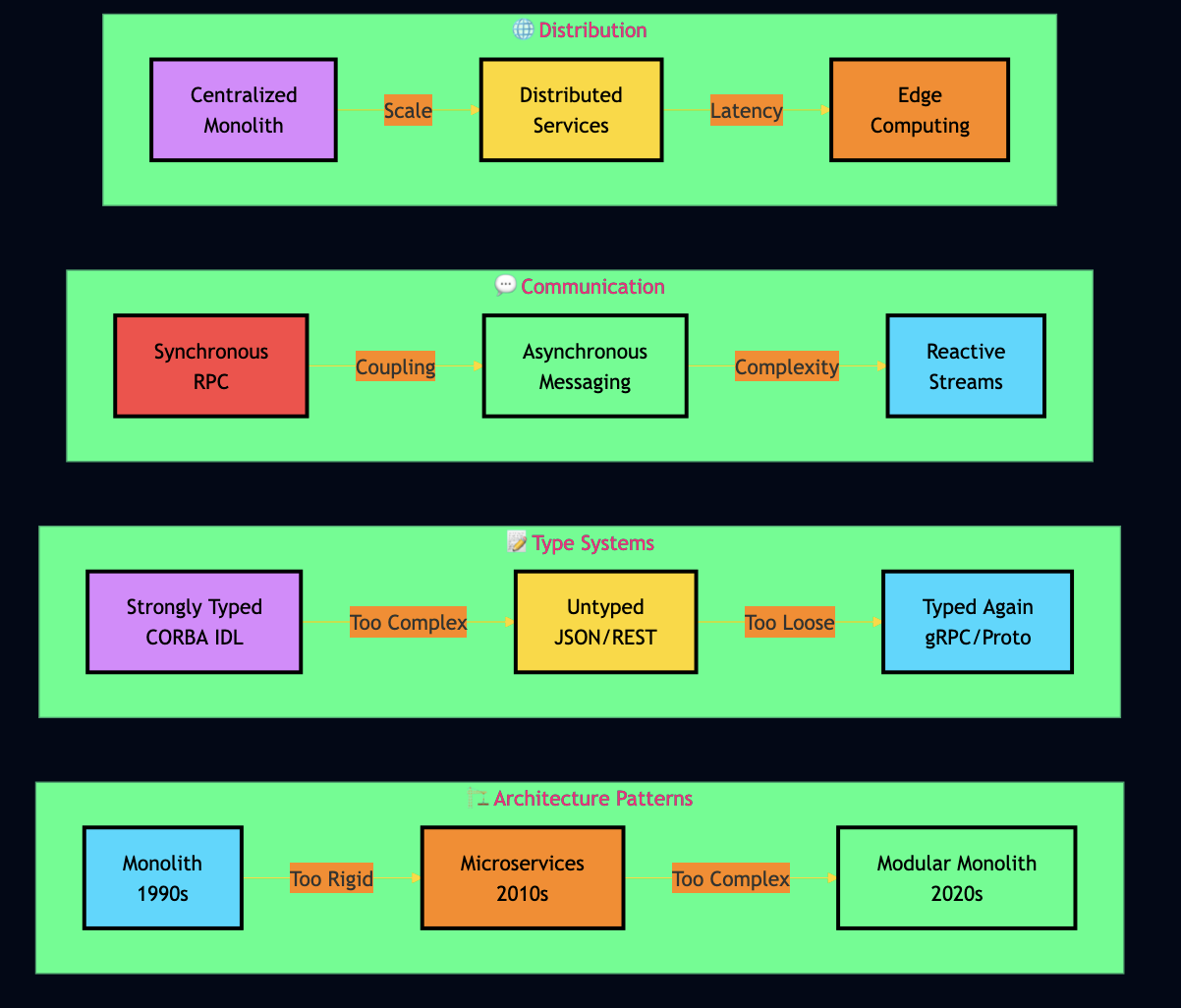

I started writing network code in the early 1990s on IBM mainframes, armed with nothing but Assembly and COBOL. Today, I build distributed AI agents using gRPC, RAG pipelines, and serverless functions. Between these worlds lie decades of technological evolution and an uncomfortable realization: we keep relearning the same lessons. Over the years, I’ve seen simple ideas triumph over complex ones. The technology keeps changing, but the problems stay the same. Network latency hasn’t gotten faster relative to CPU speed. Distributed systems are still hard. Complexity still kills projects. And every new generation has to learn that abstractions leak. I’ll show you the technologies I’ve used, the mistakes I’ve made, and most importantly, what the past teaches us about building better systems in the future.

The Mainframe Era

CICS and 3270 Terminals

I started my career on IBM mainframes running CICS, which was used to build online applications accessed through 3270 “green screen” terminals. It used LU6.2 (Logical Unit 6.2) protocol, part of IBM’s Systems Network Architecture (SNA) to provide peer-to-peer communication. Here’s what a typical CICS application looked like in COBOL:

IDENTIFICATION DIVISION.

PROGRAM-ID. CUSTOMER-INQUIRY.

DATA DIVISION.

WORKING-STORAGE SECTION.

01 CUSTOMER-REC.

05 CUST-ID PIC 9(8).

05 CUST-NAME PIC X(30).

05 CUST-BALANCE PIC 9(7)V99.

LINKAGE SECTION.

01 DFHCOMMAREA.

05 COMM-CUST-ID PIC 9(8).

PROCEDURE DIVISION.

EXEC CICS

RECEIVE MAP('CUSTMAP')

MAPSET('CUSTSET')

INTO(CUSTOMER-REC)

END-EXEC.

EXEC CICS

READ FILE('CUSTFILE')

INTO(CUSTOMER-REC)

RIDFLD(COMM-CUST-ID)

END-EXEC.

EXEC CICS

SEND MAP('RESULTMAP')

MAPSET('CUSTSET')

FROM(CUSTOMER-REC)

END-EXEC.

EXEC CICS RETURN END-EXEC.

The CICS environment handled all the complexity—transaction management, terminal I/O, file access, and inter-system communication. For the user interface, I used Basic Mapping Support (BMS), which was notoriously finicky. You had to define screen layouts in a rigid format specifying exactly where each field appeared on the 24×80 character grid:

CUSTMAP DFHMSD TYPE=&SYSPARM, X

MODE=INOUT, X

LANG=COBOL, X

CTRL=FREEKB

DFHMDI SIZE=(24,80)

CUSTID DFHMDF POS=(05,20), X

LENGTH=08, X

ATTRB=(UNPROT,NUM), X

INITIAL='________'

CUSTNAME DFHMDF POS=(07,20), X

LENGTH=30, X

ATTRB=PROT

This was so painful that I wrote my own tool to convert simple text-based UI templates into BMS format. Looking back, this was my first foray into creating developer tools. Key lesson I learned from the mainframe era was that developer experience mattered. Cumbersome tools slow down development and introduce errors.

Moving to UNIX

Berkeley Sockets

After working on mainframes for a couple of years, I saw the mainframes were already in decline and I then transitioned to C and UNIX systems, which I studied previously in my college. I learned about Berkeley Sockets, which was a lot more powerful and you had complete control over the network. Here’s a simple TCP server in C using Berkeley Sockets:

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#define PORT 8080

#define BUFFER_SIZE 1024

int main() {

int server_fd, client_fd;

struct sockaddr_in server_addr, client_addr;

socklen_t client_len = sizeof(client_addr);

char buffer[BUFFER_SIZE];

// Create socket

server_fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

if (server_fd < 0) {

perror("socket failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Set socket options to reuse address

int opt = 1;

if (setsockopt(server_fd, SOL_SOCKET, SO_REUSEADDR,

&opt, sizeof(opt)) < 0) {

perror("setsockopt failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Bind to address

memset(&server_addr, 0, sizeof(server_addr));

server_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

server_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

server_addr.sin_port = htons(PORT);

if (bind(server_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&server_addr,

sizeof(server_addr)) < 0) {

perror("bind failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Listen for connections

if (listen(server_fd, 10) < 0) {

perror("listen failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

printf("Server listening on port %d\n", PORT);

while (1) {

// Accept connection

client_fd = accept(server_fd,

(struct sockaddr *)&client_addr,

&client_len);

if (client_fd < 0) {

perror("accept failed");

continue;

}

// Read request

ssize_t bytes_read = recv(client_fd, buffer,

BUFFER_SIZE - 1, 0);

if (bytes_read > 0) {

buffer[bytes_read] = '\0';

printf("Received: %s\n", buffer);

// Send response

const char *response = "Message received\n";

send(client_fd, response, strlen(response), 0);

}

close(client_fd);

}

close(server_fd);

return 0;

}

As you can see, you had to track a lot of housekeeping like socket creation, binding, listening, accepting, reading, writing, and meticulous error handling at every step. Memory management was entirely manual—forget to close() a file descriptor and you’d leak resources. If you make a mistake with recv() buffer sizes and you’d overflow memory. I also experimented with Fast Sockets from UC Berkeley, which used kernel bypass techniques for lower latency and offered better performance.

Key lesson I learned was that low-level control comes at a steep cost. The cognitive load of managing these details makes it nearly impossible to focus on business logic.

Sun RPC and XDR

When working for a physics lab with a large computing facilities consists of Sun workstations, Solaris, and SPARC processors, I discovered Sun RPC (Remote Procedure Call) with XDR (External Data Representation). XDR solved a critical problem: how do you exchange data between machines with different architectures? A SPARC processor uses big-endian byte ordering, while x86 uses little-endian. XDR provided a canonical, architecture-neutral format for representing data. Here’s an XDR definition file (types.x):

/* Define a structure for customer data */

struct customer {

int customer_id;

string name<30>;

float balance;

};

/* Define the RPC program */

program CUSTOMER_PROG {

version CUSTOMER_VERS {

int ADD_CUSTOMER(customer) = 1;

customer GET_CUSTOMER(int) = 2;

} = 1;

} = 0x20000001;

You’d run rpcgen on this file:

$ rpcgen types.x

This generated the client stub, server stub, and XDR serialization code automatically. Here’s what the server implementation looked like:

#include "types.h"

int *add_customer_1_svc(customer *cust, struct svc_req *rqstp) {

static int result;

// Add customer to database

printf("Adding customer: %s (ID: %d)\n",

cust->name, cust->customer_id);

result = 1; // Success

return &result;

}

customer *get_customer_1_svc(int *cust_id, struct svc_req *rqstp) {

static customer result;

// Fetch from database

result.customer_id = *cust_id;

result.name = strdup("John Doe");

result.balance = 1000.50;

return &result;

}

And the client:

#include "types.h"

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

CLIENT *clnt;

customer cust;

int *result;

clnt = clnt_create("localhost", CUSTOMER_PROG,

CUSTOMER_VERS, "tcp");

if (clnt == NULL) {

clnt_pcreateerror("localhost");

exit(1);

}

// Call remote procedure

cust.customer_id = 123;

cust.name = "Alice Smith";

cust.balance = 5000.00;

result = add_customer_1(&cust, clnt);

if (result == NULL) {

clnt_perror(clnt, "call failed");

}

clnt_destroy(clnt);

return 0;

}

This was my first introduction to Interface Definition Languages (IDL) and I found that defining the contract once and generating code automatically reduces errors. This pattern would reappear in CORBA, Protocol Buffers, and gRPC.

Parallel Computing

During my graduate and post-graduate studies in mid 1990s while working full time, I researched into the parallel and distributed computing. I worked with MPI (Message Passing Interface) and IBM’s MPL on SP1/SP2 systems. MPI provided collective operations like broadcast, scatter, gather, and reduce (predecessor to Hadoop like map/reduce). Here’s a simple MPI example that computes the sum of an array in parallel:

#include <mpi.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define ARRAY_SIZE 1000

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

int rank, size;

int data[ARRAY_SIZE];

int local_sum = 0, global_sum = 0;

int chunk_size, start, end;

MPI_Init(&argc, &argv);

MPI_Comm_rank(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &rank);

MPI_Comm_size(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &size);

// Initialize data on root

if (rank == 0) {

for (int i = 0; i < ARRAY_SIZE; i++) {

data[i] = i + 1;

}

}

// Broadcast data to all processes

MPI_Bcast(data, ARRAY_SIZE, MPI_INT, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD);

// Each process computes sum of its chunk

chunk_size = ARRAY_SIZE / size;

start = rank * chunk_size;

end = (rank == size - 1) ? ARRAY_SIZE : start + chunk_size;

for (int i = start; i < end; i++) {

local_sum += data[i];

}

// Reduce all local sums to global sum

MPI_Reduce(&local_sum, &global_sum, 1, MPI_INT,

MPI_SUM, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD);

if (rank == 0) {

printf("Global sum: %d\n", global_sum);

}

MPI_Finalize();

return 0;

}

For my post-graduate project, I built JavaNOW (Java on Networks of Workstations), which was inspired by Linda’s tuple spaces and MPI’s collective operations, but implemented in pure Java for portability. The key innovation was our Actor-inspired model. Instead of heavyweight processes communicating through message passing, I used lightweight Java threads with an Entity Space (distributed associative memory) where “actors” could put and get entities asynchronously. Here’s a simple example:

public class SumTask extends ActiveEntity {

public Object execute(Object arg, JavaNOWAPI api) {

Integer myId = (Integer) arg;

EntitySpace workspace = new EntitySpace("RESULTS");

// Compute partial sum

int partialSum = 0;

for (int i = myId * 100; i < (myId + 1) * 100; i++) {

partialSum += i;

}

// Store result in EntitySpace

return new Integer(partialSum);

}

}

// Main application

public class ParallelSum extends JavaNOWApplication {

public void master() {

EntitySpace workspace = new EntitySpace("RESULTS");

// Spawn parallel tasks

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

ActiveEntity task = new SumTask(new Integer(i));

getJavaNOWAPI().eval(workspace, task, new Integer(i));

}

// Collect results

int totalSum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

Entity result = getJavaNOWAPI().get(

workspace, new Entity(new Integer(i)));

totalSum += ((Integer)result.getEntityValue()).intValue();

}

System.out.println("Total sum: " + totalSum);

}

public void slave(int id) {

// Slave nodes wait for work

}

}

Since then, I have seen the Actor model have gained a wide adoption. For example, today’s serverless functions (AWS Lambda, Azure Functions, Google Cloud Functions) and modern frameworks like Akka, Orleans, and Dapr all embrace Actor-inspired patterns.

Novell and CGI

I also briefly worked with Novell’s IPX (Internetwork Packet Exchange) protocol, which had painful APIs. Here’s a taste of IPX socket programming (simplified):

#include <nwcalls.h>

#include <nwipxspx.h>

int main() {

IPXAddress server_addr;

IPXPacket packet;

WORD socket_number = 0x4000;

// Open IPX socket

IPXOpenSocket(socket_number, 0);

// Setup address

memset(&server_addr, 0, sizeof(IPXAddress));

memcpy(server_addr.network, target_network, 4);

memcpy(server_addr.node, target_node, 6);

server_addr.socket = htons(socket_number);

// Send packet

packet.packetType = 4; // IPX packet type

memcpy(packet.data, "Hello", 5);

IPXSendPacket(socket_number, &server_addr, &packet);

IPXCloseSocket(socket_number);

return 0;

}

Early Web Development with CGI

When the web emerged in early 1990s, I built applications using CGI (Common Gateway Interface) with Perl and C. I deployed these on Apache HTTP Server, which was the first production-quality open source web server and quickly became the dominant web server of the 1990s. Apache used process-driven concurrency where it forked a new process for each request or maintained a pool of pre-forked processes. CGI was conceptually simple: the web server launched a new UNIX process for every request, passing input via stdin and receiving output via stdout. Here’s a simple Perl CGI script:

#!/usr/bin/perl

use strict;

use warnings;

use CGI;

my $cgi = CGI->new;

print $cgi->header('text/html');

print "<html><body>\n";

print "<h1>Hello from CGI!</h1>\n";

my $name = $cgi->param('name') || 'Guest';

print "<p>Welcome, $name!</p>\n";

# Simulate database query

my $user_count = 42;

print "<p>Total users: $user_count</p>\n";

print "</body></html>\n";

And in C:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

int main() {

char *query_string = getenv("QUERY_STRING");

printf("Content-Type: text/html\n\n");

printf("<html><body>\n");

printf("<h1>CGI in C</h1>\n");

if (query_string) {

printf("<p>Query string: %s</p>\n", query_string);

}

printf("</body></html>\n");

return 0;

}

Later, I migrated to more performant servers: Tomcat for Java servlets, Jetty as an embedded server, and Netty for building custom high-performance network applications. These servers used asynchronous I/O and lightweight threads (or even non-blocking event loops in Netty‘s case).

Key Lesson I learned was that scalability matters. The CGI model’s inability to maintain persistent connections or share state made it unsuitable for modern web applications. The shift from process-per-request to thread pools and then to async I/O represented fundamental improvements in how we handle concurrency.

Java Adoption

When Java was released in 1995, I adopted it wholeheartedly. It saved developers from manual memory management using malloc() and free() debugging. Network programming became far more approachable:

import java.io.*;

import java.net.*;

public class SimpleServer {

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

int port = 8080;

try (ServerSocket serverSocket = new ServerSocket(port)) {

System.out.println("Server listening on port " + port);

while (true) {

try (Socket clientSocket = serverSocket.accept();

BufferedReader in = new BufferedReader(

new InputStreamReader(clientSocket.getInputStream()));

PrintWriter out = new PrintWriter(

clientSocket.getOutputStream(), true)) {

String request = in.readLine();

System.out.println("Received: " + request);

out.println("Message received");

}

}

}

}

}

Java Threads

I had previously used pthreads in C, which were hard to use but Java’s threading model was far simpler:

public class ConcurrentServer {

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

ServerSocket serverSocket = new ServerSocket(8080);

while (true) {

Socket clientSocket = serverSocket.accept();

// Spawn thread to handle client

new Thread(new ClientHandler(clientSocket)).start();

}

}

static class ClientHandler implements Runnable {

private Socket socket;

public ClientHandler(Socket socket) {

this.socket = socket;

}

public void run() {

try (BufferedReader in = new BufferedReader(

new InputStreamReader(socket.getInputStream()));

PrintWriter out = new PrintWriter(

socket.getOutputStream(), true)) {

String request = in.readLine();

// Process request

out.println("Response");

} catch (IOException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

} finally {

try { socket.close(); } catch (IOException e) {}

}

}

}

}

Java’s synchronized keyword simplified thread-safe programming:

public class ThreadSafeCounter {

private int count = 0;

public synchronized void increment() {

count++;

}

public synchronized int getCount() {

return count;

}

}

This was so much easier than managing mutexes, condition variables, and semaphores in C!

Java RMI: Remote Objects Made

When Java added RMI (1997), distributed objects became practical. You could invoke methods on objects running on remote machines almost as if they were local. Define a remote interface:

import java.rmi.Remote;

import java.rmi.RemoteException;

public interface Calculator extends Remote {

int add(int a, int b) throws RemoteException;

int multiply(int a, int b) throws RemoteException;

}

Implement it:

import java.rmi.server.UnicastRemoteObject;

import java.rmi.RemoteException;

public class CalculatorImpl extends UnicastRemoteObject

implements Calculator {

public CalculatorImpl() throws RemoteException {

super();

}

public int add(int a, int b) throws RemoteException {

return a + b;

}

public int multiply(int a, int b) throws RemoteException {

return a * b;

}

}

Server:

import java.rmi.Naming;

import java.rmi.registry.LocateRegistry;

public class Server {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

LocateRegistry.createRegistry(1099);

Calculator calc = new CalculatorImpl();

Naming.rebind("Calculator", calc);

System.out.println("Server ready");

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

Client:

import java.rmi.Naming;

public class Client {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

Calculator calc = (Calculator) Naming.lookup(

"rmi://localhost/Calculator");

int result = calc.add(5, 3);

System.out.println("5 + 3 = " + result);

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

I found that RMI was constrained and everything had to extend Remote, and you were stuck with Java-to-Java communication. Key lesson I learned was that abstractions that feel natural to developers get adopted.

JINI: RMI with Service Discovery

At a travel booking company in the mid 2000s, I used JINI, which Sun Microsystems pitched as “RMI on steroids.” JINI extended RMI with automatic service discovery, leasing, and distributed events. The core idea: services could join a network, advertise themselves, and be discovered by clients without hardcoded locations. Here’s a JINI service interface and registration:

import net.jini.core.lookup.ServiceRegistrar;

import net.jini.discovery.LookupDiscovery;

import net.jini.lease.LeaseRenewalManager;

import java.rmi.Remote;

import java.rmi.RemoteException;

// Service interface

public interface BookingService extends Remote {

String searchFlights(String origin, String destination)

throws RemoteException;

boolean bookFlight(String flightId, String passenger)

throws RemoteException;

}

// Service provider

public class BookingServiceProvider implements DiscoveryListener {

public void discovered(DiscoveryEvent event) {

ServiceRegistrar[] registrars = event.getRegistrars();

for (ServiceRegistrar registrar : registrars) {

try {

BookingService service = new BookingServiceImpl();

Entry[] attributes = new Entry[] {

new Name("FlightBookingService")

};

ServiceItem item = new ServiceItem(null, service, attributes);

ServiceRegistration reg = registrar.register(

item, Lease.FOREVER);

// Auto-renew lease

leaseManager.renewUntil(reg.getLease(), Lease.FOREVER, null);

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

}

Client discovery and usage:

public class BookingClient implements DiscoveryListener {

public void discovered(DiscoveryEvent event) {

ServiceRegistrar[] registrars = event.getRegistrars();

for (ServiceRegistrar registrar : registrars) {

try {

ServiceTemplate template = new ServiceTemplate(

null, new Class[] { BookingService.class }, null);

ServiceItem item = registrar.lookup(template);

if (item != null) {

BookingService booking = (BookingService) item.service;

String flights = booking.searchFlights("SFO", "NYC");

booking.bookFlight("FL123", "John Smith");

}

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

}

Though, JINI provided automatic discovery, leasing and location transparency but it was too complex and only supported Java ecosystem. The ideas were sound and reappeared later in service meshes (Consul, Eureka) and Kubernetes service discovery. I learned that service discovery is essential for dynamic systems, but the implementation must be simple.

CORBA

I used CORBA (Common Object Request Broker Architecture) for many years in 1990s when building intelligent traffic Systems. CORBA promised the language-independent, platform-independent distributed objects. You could write a service in C++, invoke it from Java, and have clients in Python using the same IDL. Here’s a simple CORBA IDL definition:

module TrafficMonitor {

struct SensorData {

long sensor_id;

float speed;

long timestamp;

};

typedef sequence<SensorData> SensorDataList;

interface TrafficService {

void reportData(in SensorData data);

SensorDataList getRecentData(in long minutes);

float getAverageSpeed();

};

};

Run the IDL compiler:

$ idl traffic.idl

This generated client stubs and server skeletons for your target language. I built a message-oriented middleware (MOM) system with CORBA that collected traffic data from road sensors and provided real-time traffic information.

C++ server implementation:

#include "TrafficService_impl.h"

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

class TrafficServiceImpl : public POA_TrafficMonitor::TrafficService {

private:

std::vector<TrafficMonitor::SensorData> data_store;

public:

void reportData(const TrafficMonitor::SensorData& data) {

data_store.push_back(data);

std::cout << "Received data from sensor "

<< data.sensor_id << std::endl;

}

TrafficMonitor::SensorDataList* getRecentData(CORBA::Long minutes) {

TrafficMonitor::SensorDataList* result =

new TrafficMonitor::SensorDataList();

// Filter data from last N minutes

time_t cutoff = time(NULL) - (minutes * 60);

for (const auto& entry : data_store) {

if (entry.timestamp >= cutoff) {

result->length(result->length() + 1);

(*result)[result->length() - 1] = entry;

}

}

return result;

}

CORBA::Float getAverageSpeed() {

if (data_store.empty()) return 0.0;

float sum = 0.0;

for (const auto& entry : data_store) {

sum += entry.speed;

}

return sum / data_store.size();

}

};

Java client:

import org.omg.CORBA.*;

import TrafficMonitor.*;

public class TrafficClient {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

// Initialize ORB

ORB orb = ORB.init(args, null);

// Get reference to service

org.omg.CORBA.Object obj =

orb.string_to_object("corbaname::localhost:1050#TrafficService");

TrafficService service = TrafficServiceHelper.narrow(obj);

// Report sensor data

SensorData data = new SensorData();

data.sensor_id = 101;

data.speed = 65.5f;

data.timestamp = (int)(System.currentTimeMillis() / 1000);

service.reportData(data);

// Get average speed

float avgSpeed = service.getAverageSpeed();

System.out.println("Average speed: " + avgSpeed + " mph");

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

However, CORBA specification was massive and different ORB (Object Request Broker) implementations like Orbix, ORBacus, and TAO couldn’t reliably interoperate despite claiming CORBA compliance. The binary protocol, IIOP, had subtle incompatibilities. CORBA did introduce valuable concepts:

- Interceptors for cross-cutting concerns (authentication, logging, monitoring)

- IDL-first design that forced clear interface definitions

- Language-neutral protocols that actually worked (sometimes)

I learned that standards designed by committee are often over-engineer. CORBA, SOAP tried to solve every problem for everyone and ended up being optimal for no one.

SOAP and WSDL

I used SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol) and WSDL (Web Services Description Language) on a number of projects in early 2000s that emerged as the standard for web services. The pitch: XML-based, platform-neutral, and “simple.” Here’s a WSDL definition:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<definitions name="CustomerService"

targetNamespace="http://example.com/customer"

xmlns="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/wsdl/"

xmlns:soap="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/wsdl/soap/"

xmlns:tns="http://example.com/customer"

xmlns:xsd="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema">

<types>

<xsd:schema targetNamespace="http://example.com/customer">

<xsd:complexType name="Customer">

<xsd:sequence>

<xsd:element name="id" type="xsd:int"/>

<xsd:element name="name" type="xsd:string"/>

<xsd:element name="balance" type="xsd:double"/>

</xsd:sequence>

</xsd:complexType>

</xsd:schema>

</types>

<message name="GetCustomerRequest">

<part name="customerId" type="xsd:int"/>

</message>

<message name="GetCustomerResponse">

<part name="customer" type="tns:Customer"/>

</message>

<portType name="CustomerPortType">

<operation name="getCustomer">

<input message="tns:GetCustomerRequest"/>

<output message="tns:GetCustomerResponse"/>

</operation>

</portType>

<binding name="CustomerBinding" type="tns:CustomerPortType">

<soap:binding transport="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/http"/>

<operation name="getCustomer">

<soap:operation soapAction="getCustomer"/>

<input>

<soap:body use="literal"/>

</input>

<output>

<soap:body use="literal"/>

</output>

</operation>

</binding>

<service name="CustomerService">

<port name="CustomerPort" binding="tns:CustomerBinding">

<soap:address location="http://example.com/customer"/>

</port>

</service>

</definitions>

A SOAP request looked like this:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<soap:Envelope

xmlns:soap="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/"

xmlns:cust="http://example.com/customer">

<soap:Header>

<cust:Authentication>

<cust:username>john</cust:username>

<cust:password>secret</cust:password>

</cust:Authentication>

</soap:Header>

<soap:Body>

<cust:getCustomer>

<cust:customerId>12345</cust:customerId>

</cust:getCustomer>

</soap:Body>

</soap:Envelope>

The response:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<soap:Envelope

xmlns:soap="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/"

xmlns:cust="http://example.com/customer">

<soap:Body>

<cust:getCustomerResponse>

<cust:customer>

<cust:id>12345</cust:id>

<cust:name>John Smith</cust:name>

<cust:balance>5000.00</cust:balance>

</cust:customer>

</cust:getCustomerResponse>

</soap:Body>

</soap:Envelope>

You can look at all that XML overhead! A simple request became hundreds of bytes of markup. As SOAP was designed by committee (IBM, Oracle, Microsoft), it tried to solve every possible enterprise problem: transactions, security, reliability, routing, orchestration. I learned that simplicity beats features and SOAP collapsed under its own weight.

Java Servlets and Filters

With Java 1.1, it added support for Servlets that provided a much better model than CGI. Instead of spawning a process per request, servlets were Java classes instantiated once and reused across requests:

import javax.servlet.*;

import javax.servlet.http.*;

import java.io.*;

public class CustomerServlet extends HttpServlet {

protected void doGet(HttpServletRequest request,

HttpServletResponse response)

throws ServletException, IOException {

String customerId = request.getParameter("id");

response.setContentType("application/json");

PrintWriter out = response.getWriter();

// Fetch customer data

Customer customer = getCustomerFromDatabase(customerId);

if (customer != null) {

out.println(String.format(

"{\"id\": \"%s\", \"name\": \"%s\", \"balance\": %.2f}",

customer.getId(), customer.getName(), customer.getBalance()

));

} else {

response.setStatus(HttpServletResponse.SC_NOT_FOUND);

out.println("{\"error\": \"Customer not found\"}");

}

}

protected void doPost(HttpServletRequest request,

HttpServletResponse response)

throws ServletException, IOException {

BufferedReader reader = request.getReader();

StringBuilder json = new StringBuilder();

String line;

while ((line = reader.readLine()) != null) {

json.append(line);

}

// Parse JSON and create customer

Customer customer = parseJsonToCustomer(json.toString());

saveCustomerToDatabase(customer);

response.setStatus(HttpServletResponse.SC_CREATED);

response.setContentType("application/json");

PrintWriter out = response.getWriter();

out.println(json.toString());

}

}

Servlet Filters

The Filter API with Java Servlets was quite powerful and it supported a chain-of-responsibility pattern for handling cross-cutting concerns:

import javax.servlet.*;

import javax.servlet.http.*;

import java.io.IOException;

public class AuthenticationFilter implements Filter {

public void doFilter(ServletRequest request,

ServletResponse response,

FilterChain chain)

throws IOException, ServletException {

HttpServletRequest httpRequest = (HttpServletRequest) request;

HttpServletResponse httpResponse = (HttpServletResponse) response;

// Check for authentication token

String token = httpRequest.getHeader("Authorization");

if (token == null || !isValidToken(token)) {

httpResponse.setStatus(HttpServletResponse.SC_UNAUTHORIZED);

httpResponse.getWriter().println("{\"error\": \"Unauthorized\"}");

return;

}

// Pass to next filter or servlet

chain.doFilter(request, response);

}

private boolean isValidToken(String token) {

// Validate token

return token.startsWith("Bearer ") &&

validateJWT(token.substring(7));

}

}

Configuration in web.xml:

<filter>

<filter-name>AuthenticationFilter</filter-name>

<filter-class>com.example.AuthenticationFilter</filter-class>

</filter>

<filter-mapping>

<filter-name>AuthenticationFilter</filter-name>

<url-pattern>/api/*</url-pattern>

</filter-mapping>

You could chain filters for compression, logging, transformation, rate limiting with clean separation of concerns without touching business logic. I previously had experienced with CORBA interceptors for injecting cross-cutting business logic and the filter pattern solved similar cross-cutting concerns problem. This pattern would reappear in service meshes and API gateways.

Enterprise Java Beans

I used Enterprise Java Beans (EJB) in late 1990s and early 2000s that attempted to make distributed objects transparent. Its key idea was that use regular Java objects and let the application server handle all the distribution, persistence, transactions, and security. Here’s what an EJB 2.x entity bean looked like:

// Remote interface

public interface Customer extends EJBObject {

String getName() throws RemoteException;

void setName(String name) throws RemoteException;

double getBalance() throws RemoteException;

void setBalance(double balance) throws RemoteException;

}

// Home interface

public interface CustomerHome extends EJBHome {

Customer create(Integer id, String name) throws CreateException, RemoteException;

Customer findByPrimaryKey(Integer id) throws FinderException, RemoteException;

}

// Bean implementation

public class CustomerBean implements EntityBean {

private Integer id;

private String name;

private double balance;

public String getName() { return name; }

public void setName(String name) { this.name = name; }

public double getBalance() { return balance; }

public void setBalance(double balance) { this.balance = balance; }

// Container callbacks

public void ejbActivate() {}

public void ejbPassivate() {}

public void ejbLoad() {}

public void ejbStore() {}

public void setEntityContext(EntityContext ctx) {}

public void unsetEntityContext() {}

public Integer ejbCreate(Integer id, String name) {

this.id = id;

this.name = name;

this.balance = 0.0;

return null;

}

public void ejbPostCreate(Integer id, String name) {}

}

The N+1 Selects Problem and Network Fallacy

The fatal flaw: EJB pretended network calls were free. I watched teams write code like this:

CustomerHome home = // ... lookup Customer customer = home.findByPrimaryKey(customerId); // Each getter is a remote call! String name = customer.getName(); // Network call double balance = customer.getBalance(); // Network call

Worse, I saw code that made remote calls in loops:

Collection customers = home.findAll();

double totalBalance = 0.0;

for (Customer customer : customers) {

// Remote call for EVERY iteration!

totalBalance += customer.getBalance();

}

This violated the first Fallacy of Distributed Computing: The network is reliable. It’s also not zero latency. What looked like simple property access actually made HTTP calls to a remote server. I had previously built distributed and parallel applications, so I understood network latency. But it blindsided most developers because EJB deliberately hid it.

I learned that you can’t hide distribution. Network calls are fundamentally different from local calls. Latency, failure modes, and semantics are different. Transparency is a lie.

REST Standard

Before REST became mainstream, I experimented with “Plain Old XML” (POX) over HTTP by just sending XML documents via HTTP POST without all the SOAP ceremony:

import requests

import xml.etree.ElementTree as ET

# Create XML request

root = ET.Element('getCustomer')

ET.SubElement(root, 'customerId').text = '12345'

xml_data = ET.tostring(root, encoding='utf-8')

# Send HTTP POST

response = requests.post(

'http://api.example.com/customer',

data=xml_data,

headers={'Content-Type': 'application/xml'}

)

# Parse response

response_tree = ET.fromstring(response.content)

name = response_tree.find('name').text

This was simpler than SOAP, but still ad-hoc. Then REST (Representational State Transfer), based on Roy Fielding’s 2000 dissertation offered a principled approach:

- Use HTTP methods semantically (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE)

- Resources have URLs

- Stateless communication

- Hypermedia as the engine of application state (HATEOAS)

Here’s a RESTful API in Python with Flask:

from flask import Flask, jsonify, request

app = Flask(__name__)

# In-memory data store

customers = {

'12345': {'id': '12345', 'name': 'John Smith', 'balance': 5000.00}

}

@app.route('/customers/<customer_id>', methods=['GET'])

def get_customer(customer_id):

customer = customers.get(customer_id)

if customer:

return jsonify(customer), 200

return jsonify({'error': 'Customer not found'}), 404

@app.route('/customers', methods=['POST'])

def create_customer():

data = request.get_json()

customer_id = data['id']

customers[customer_id] = data

return jsonify(data), 201

@app.route('/customers/<customer_id>', methods=['PUT'])

def update_customer(customer_id):

if customer_id not in customers:

return jsonify({'error': 'Customer not found'}), 404

data = request.get_json()

customers[customer_id].update(data)

return jsonify(customers[customer_id]), 200

@app.route('/customers/<customer_id>', methods=['DELETE'])

def delete_customer(customer_id):

if customer_id in customers:

del customers[customer_id]

return '', 204

return jsonify({'error': 'Customer not found'}), 404

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True)

Client code became trivial:

import requests

# GET customer

response = requests.get('http://localhost:5000/customers/12345')

if response.status_code == 200:

customer = response.json()

print(f"Customer: {customer['name']}")

# Create new customer

new_customer = {

'id': '67890',

'name': 'Alice Johnson',

'balance': 3000.00

}

response = requests.post(

'http://localhost:5000/customers',

json=new_customer

)

# Update customer

update_data = {'balance': 3500.00}

response = requests.put(

'http://localhost:5000/customers/67890',

json=update_data

)

# Delete customer

response = requests.delete('http://localhost:5000/customers/67890')

Hypermedia and HATEOAS

True REST embraced hypermedia—responses included links to related resources:

{

"id": "12345",

"name": "John Smith",

"balance": 5000.00,

"_links": {

"self": {"href": "/customers/12345"},

"orders": {"href": "/customers/12345/orders"},

"transactions": {"href": "/customers/12345/transactions"}

}

}

In practice, most APIs called “REST” weren’t truly RESTful and didn’t implement HATEOAS or use HTTP status codes correctly. But even “REST-ish” APIs were far simpler than SOAP. Key lesson I leared was that REST succeeded because it built on HTTP, something every platform already supported. No new protocols, no complex tooling. Just URLs, HTTP verbs, and JSON.

JSON Replaces XML

With adoption of REST, I saw a decline of XML Web Services (JAX-WS) and I used JAX-RS for REST services that supported JSON payload. XML required verbose markup:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<customer>

<id>12345</id>

<name>John Smith</name>

<balance>5000.00</balance>

<orders>

<order>

<id>001</id>

<date>2024-01-15</date>

<total>99.99</total>

</order>

<order>

<id>002</id>

<date>2024-02-20</date>

<total>149.50</total>

</order>

</orders>

</customer>

The same data in JSON:

{

"id": "12345",

"name": "John Smith",

"balance": 5000.00,

"orders": [

{

"id": "001",

"date": "2024-01-15",

"total": 99.99

},

{

"id": "002",

"date": "2024-02-20",

"total": 149.50

}

]

}

JSON does have limitations. It doesn’t natively support references or circular structures, making recursive relationships awkward:

{

"id": "A",

"children": [

{

"id": "B",

"parent_id": "A"

}

]

}

You have to encode references manually, unlike some XML schemas that support IDREF.

Erlang/OTP

I learned about actor model in college and built a framework based on actors and Linda memory model. In the mid-2000s, I encountered Erlang that used actors for building distributed systems. Erlang was designed in the 1980s at Ericsson for building telecom switches and is based on following design:

- “Let it crash” philosophy

- No shared memory between processes

- Lightweight processes (not OS threads—Erlang processes)

- Supervision trees for fault recovery

- Hot code swapping for zero-downtime updates

Here’s what an Erlang actor (process) looks like:

-module(customer_server).

-export([start/0, init/0, get_customer/1, update_balance/2]).

% Start the server

start() ->

Pid = spawn(customer_server, init, []),

register(customer_server, Pid),

Pid.

% Initialize with empty state

init() ->

State = #{}, % Empty map

loop(State).

% Main loop - handle messages

loop(State) ->

receive

{get_customer, CustomerId, From} ->

Customer = maps:get(CustomerId, State, not_found),

From ! {customer, Customer},

loop(State);

{update_balance, CustomerId, NewBalance, From} ->

Customer = maps:get(CustomerId, State),

UpdatedCustomer = Customer#{balance => NewBalance},

NewState = maps:put(CustomerId, UpdatedCustomer, State),

From ! {ok, updated},

loop(NewState);

{add_customer, CustomerId, Customer, From} ->

NewState = maps:put(CustomerId, Customer, State),

From ! {ok, added},

loop(NewState);

stop ->

ok;

_ ->

loop(State)

end.

% Client functions

get_customer(CustomerId) ->

customer_server ! {get_customer, CustomerId, self()},

receive

{customer, Customer} -> Customer

after 5000 ->

timeout

end.

update_balance(CustomerId, NewBalance) ->

customer_server ! {update_balance, CustomerId, NewBalance, self()},

receive

{ok, updated} -> ok

after 5000 ->

timeout

end.

Erlang made concurrency became simple by using messaging passing with actors.

The Supervision Tree

A key innovation of Erlang was supervision trees. You organized processes in a hierarchy, and supervisors would restart crashed children:

-module(customer_supervisor).

-behaviour(supervisor).

-export([start_link/0, init/1]).

start_link() ->

supervisor:start_link({local, ?MODULE}, ?MODULE, []).

init([]) ->

% Supervisor strategy

SupFlags = #{

strategy => one_for_one, % Restart only failed child

intensity => 5, % Max 5 restarts

period => 60 % Per 60 seconds

},

% Child specifications

ChildSpecs = [

#{

id => customer_server,

start => {customer_server, start, []},

restart => permanent, % Always restart

shutdown => 5000,

type => worker,

modules => [customer_server]

},

#{

id => order_server,

start => {order_server, start, []},

restart => permanent,

shutdown => 5000,

type => worker,

modules => [order_server]

}

],

{ok, {SupFlags, ChildSpecs}}.

If a process crashed, the supervisor automatically restarted it and the system self-healed. A key lesson I learned from actor model and Erlang was that a shared mutable state is the enemy. Message passing with isolated state is simpler, more reliable, and easier to reason about. Today, AWS Lambda, Azure Durable Functions, and frameworks like Akka all embrace the Actor model.

Distributed Erlang

Erlang made distributed computing almost trivial. Processes on different nodes communicated identically to local processes:

% On node1@host1

RemotePid = spawn('node2@host2', module, function, [args]),

RemotePid ! {message, data}.

% On node2@host2 - receives the message

receive

{message, Data} ->

io:format("Received: ~p~n", [Data])

end.

The VM handled all the complexity of node discovery, connection management, and message routing. Today’s serverless functions are actors and kubernetes pods are supervised processes.

Asynchronous Messaging

As systems grew more complex, asynchronous messaging became essential. I worked extensively with Oracle Tuxedo, IBM MQSeries, WebLogic JMS, WebSphere MQ, and later ActiveMQ, MQTT / AMQP, ZeroMQ and RabbitMQ primarily for inter-service communication and asynchronous processing. Here’s a JMS producer in Java:

import javax.jms.*;

import javax.naming.*;

public class OrderProducer {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Context ctx = new InitialContext();

ConnectionFactory factory =

(ConnectionFactory) ctx.lookup("ConnectionFactory");

Queue queue = (Queue) ctx.lookup("OrderQueue");

Connection connection = factory.createConnection();

Session session = connection.createSession(

false, Session.AUTO_ACKNOWLEDGE);

MessageProducer producer = session.createProducer(queue);

// Create message

TextMessage message = session.createTextMessage();

message.setText("{ \"orderId\": \"12345\", " +

"\"customerId\": \"67890\", " +

"\"amount\": 99.99 }");

// Send message

producer.send(message);

System.out.println("Order sent: " + message.getText());

connection.close();

}

}

JMS consumer:

import javax.jms.*;

import javax.naming.*;

public class OrderConsumer implements MessageListener {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Context ctx = new InitialContext();

ConnectionFactory factory =

(ConnectionFactory) ctx.lookup("ConnectionFactory");

Queue queue = (Queue) ctx.lookup("OrderQueue");

Connection connection = factory.createConnection();

Session session = connection.createSession(

false, Session.AUTO_ACKNOWLEDGE);

MessageConsumer consumer = session.createConsumer(queue);

consumer.setMessageListener(new OrderConsumer());

connection.start();

System.out.println("Waiting for messages...");

Thread.sleep(Long.MAX_VALUE); // Keep running

}

public void onMessage(Message message) {

try {

TextMessage textMessage = (TextMessage) message;

System.out.println("Received order: " +

textMessage.getText());

// Process order

processOrder(textMessage.getText());

} catch (JMSException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

private void processOrder(String orderJson) {

// Business logic here

}

}

Asynchronous messaging is essential for building resilient, scalable systems. It decouples producers from consumers, provides natural backpressure, and enables event-driven architectures.

Spring Framework and Aspect-Oriented Programming

In early 2000, I used aspect oriented programming (AOP) to inject cross cutting concerns like logging, security, monitoring, etc. Here is a typical example:

@Aspect

@Component

public class LoggingAspect {

private static final Logger logger =

LoggerFactory.getLogger(LoggingAspect.class);

@Before("execution(* com.example.service.*.*(..))")

public void logBefore(JoinPoint joinPoint) {

logger.info("Executing: " +

joinPoint.getSignature().getName());

}

@AfterReturning(

pointcut = "execution(* com.example.service.*.*(..))",

returning = "result")

public void logAfterReturning(JoinPoint joinPoint, Object result) {

logger.info("Method " +

joinPoint.getSignature().getName() +

" returned: " + result);

}

@Around("@annotation(com.example.Monitored)")

public Object measureTime(ProceedingJoinPoint joinPoint)

throws Throwable {

long start = System.currentTimeMillis();

Object result = joinPoint.proceed();

long time = System.currentTimeMillis() - start;

logger.info(joinPoint.getSignature().getName() +

" took " + time + " ms");

return result;

}

}

I later adopted Spring Framework that revolutionized Java development with dependency injection and aspect-oriented programming (AOP):

// Spring configuration

@Configuration

public class AppConfig {

@Bean

public CustomerService customerService() {

return new CustomerServiceImpl(customerRepository());

}

@Bean

public CustomerRepository customerRepository() {

return new DatabaseCustomerRepository(dataSource());

}

@Bean

public DataSource dataSource() {

DriverManagerDataSource ds = new DriverManagerDataSource();

ds.setDriverClassName("com.mysql.jdbc.Driver");

ds.setUrl("jdbc:mysql://localhost/mydb");

return ds;

}

}

// Service class

@Service

public class CustomerServiceImpl implements CustomerService {

private final CustomerRepository repository;

@Autowired

public CustomerServiceImpl(CustomerRepository repository) {

this.repository = repository;

}

@Transactional

public void updateBalance(String customerId, double newBalance) {

Customer customer = repository.findById(customerId);

customer.setBalance(newBalance);

repository.save(customer);

}

}

Spring Remoting

Spring added its own remoting protocols. HTTP Invoker serialized Java objects over HTTP:

// Server configuration

@Configuration

public class ServerConfig {

@Bean

public HttpInvokerServiceExporter customerService() {

HttpInvokerServiceExporter exporter =

new HttpInvokerServiceExporter();

exporter.setService(customerServiceImpl());

exporter.setServiceInterface(CustomerService.class);

return exporter;

}

}

// Client configuration

@Configuration

public class ClientConfig {

@Bean

public HttpInvokerProxyFactoryBean customerService() {

HttpInvokerProxyFactoryBean proxy =

new HttpInvokerProxyFactoryBean();

proxy.setServiceUrl("http://localhost:8080/customer");

proxy.setServiceInterface(CustomerService.class);

return proxy;

}

}

I learned that AOP addressed cross-cutting concerns elegantly for monoliths. But in microservices, these concerns moved to the infrastructure layer like service meshes, API gateways, and sidecars.

Proprietary Protocols

When working for large companies like Amazon, I encountered Amazon Coral, which is a proprietary RPC framework influenced by CORBA. Coral used an IDL to define service interfaces and supported multiple languages:

// Coral IDL

namespace com.amazon.example

structure CustomerData {

1: required integer customerId

2: required string name

3: optional double balance

}

service CustomerService {

CustomerData getCustomer(1: integer customerId)

void updateCustomer(1: CustomerData customer)

list<CustomerData> listCustomers()

}

The IDL compiler generated client and server code for Java, C++, and other languages. Coral handled serialization, versioning, and service discovery. When I later worked for AWS, I used Smithy that was successor Coral, which Amazon open-sourced. Here is a similar example of a Smithy contract:

namespace com.example

service CustomerService {

version: "2024-01-01"

operations: [

GetCustomer

UpdateCustomer

ListCustomers

]

}

@readonly

operation GetCustomer {

input: GetCustomerInput

output: GetCustomerOutput

errors: [CustomerNotFound]

}

structure GetCustomerInput {

@required

customerId: String

}

structure GetCustomerOutput {

@required

customer: Customer

}

structure Customer {

@required

customerId: String

@required

name: String

balance: Double

}

@error("client")

structure CustomerNotFound {

@required

message: String

}

I learned IDL-first design remains valuable. Smithy learned from CORBA, Protocol Buffers, and Thrift.

Long Polling, WebSockets, and Real-Time

In late 2000s, I built real-time applications for streaming financial charts and technical data. I used long polling where the client made a request that the server held open until data was available:

// Client-side long polling

function pollServer() {

fetch('/api/events')

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => {

console.log('Received event:', data);

updateUI(data);

// Immediately poll again

pollServer();

})

.catch(error => {

console.error('Polling error:', error);

// Retry after delay

setTimeout(pollServer, 5000);

});

}

pollServer();

Server-side (Node.js):

const express = require('express');

const app = express();

let pendingRequests = [];

app.get('/api/events', (req, res) => {

// Hold request open

pendingRequests.push(res);

// Timeout after 30 seconds

setTimeout(() => {

const index = pendingRequests.indexOf(res);

if (index !== -1) {

pendingRequests.splice(index, 1);

res.json({ type: 'heartbeat' });

}

}, 30000);

});

// When an event occurs

function broadcastEvent(event) {

pendingRequests.forEach(res => {

res.json(event);

});

pendingRequests = [];

}

WebSockets

I also used WebSockets for real time applications that supported true bidirectional communication. However, earlier browsers didn’t fully support them so I used long polling as a fallback when websockets were not supported:

// Server (Node.js with ws library)

const WebSocket = require('ws');

const wss = new WebSocket.Server({ port: 8080 });

wss.on('connection', (ws) => {

console.log('Client connected');

// Send initial data

ws.send(JSON.stringify({

type: 'INIT',

data: getInitialData()

}));

// Handle messages

ws.on('message', (message) => {

const msg = JSON.parse(message);

if (msg.type === 'SUBSCRIBE') {

subscribeToSymbol(ws, msg.symbol);

}

});

ws.on('close', () => {

console.log('Client disconnected');

unsubscribeAll(ws);

});

});

// Stream live data

function streamPriceUpdate(symbol, price) {

wss.clients.forEach((client) => {

if (client.readyState === WebSocket.OPEN) {

if (isSubscribed(client, symbol)) {

client.send(JSON.stringify({

type: 'PRICE_UPDATE',

symbol: symbol,

price: price,

timestamp: Date.now()

}));

}

}

});

}

Client:

const ws = new WebSocket('ws://localhost:8080');

ws.onopen = () => {

console.log('Connected to server');

// Subscribe to symbols

ws.send(JSON.stringify({

type: 'SUBSCRIBE',

symbol: 'AAPL'

}));

};

ws.onmessage = (event) => {

const message = JSON.parse(event.data);

switch (message.type) {

case 'INIT':

initializeChart(message.data);

break;

case 'PRICE_UPDATE':

updateChart(message.symbol, message.price);

break;

}

};

ws.onerror = (error) => {

console.error('WebSocket error:', error);

};

ws.onclose = () => {

console.log('Disconnected, attempting reconnect...');

setTimeout(connectWebSocket, 1000);

};

I learned that different problems need different protocols. REST works for request-response. WebSockets excel for real-time bidirectional communication.

Vert.x and Hazelcast for High-Performance Streaming

For a production streaming chart system handling high-volume market data, I used Vert.x with Hazelcast. Vert.x is a reactive toolkit built on Netty that excels at handling thousands of concurrent connections with minimal resources. Hazelcast provided distributed caching and coordination across multiple Vert.x instances. Market data flowed into Hazelcast distributed topics, Vert.x instances subscribed to these topics and pushed updates to connected WebSocket clients. If WebSocket wasn’t supported, we fell back to long polling automatically.

import io.vertx.core.Vertx;

import io.vertx.core.http.HttpServer;

import io.vertx.core.http.ServerWebSocket;

import com.hazelcast.core.Hazelcast;

import com.hazelcast.core.HazelcastInstance;

import com.hazelcast.core.ITopic;

import com.hazelcast.core.Message;

import com.hazelcast.core.MessageListener;

import java.util.concurrent.ConcurrentHashMap;

import java.util.Set;

public class MarketDataServer {

private final Vertx vertx;

private final HazelcastInstance hazelcast;

private final ConcurrentHashMap<String, Set<ServerWebSocket>> subscriptions;

public MarketDataServer() {

this.vertx = Vertx.vertx();

this.hazelcast = Hazelcast.newHazelcastInstance();

this.subscriptions = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

// Subscribe to market data topic

ITopic<MarketData> topic = hazelcast.getTopic("market-data");

topic.addMessageListener(new MessageListener<MarketData>() {

public void onMessage(Message<MarketData> message) {

broadcastToSubscribers(message.getMessageObject());

}

});

}

public void start() {

HttpServer server = vertx.createHttpServer();

server.webSocketHandler(ws -> {

String path = ws.path();

if (path.startsWith("/stream/")) {

String symbol = path.substring(8);

handleWebSocketConnection(ws, symbol);

} else {

ws.reject();

}

});

// Long polling fallback

server.requestHandler(req -> {

if (req.path().startsWith("/poll/")) {

String symbol = req.path().substring(6);

handleLongPolling(req, symbol);

}

});

server.listen(8080, result -> {

if (result.succeeded()) {

System.out.println("Market data server started on port 8080");

}

});

}

private void handleWebSocketConnection(ServerWebSocket ws, String symbol) {

subscriptions.computeIfAbsent(symbol, k -> ConcurrentHashMap.newKeySet())

.add(ws);

ws.closeHandler(v -> {

Set<ServerWebSocket> sockets = subscriptions.get(symbol);

if (sockets != null) {

sockets.remove(ws);

}

});

// Send initial snapshot from Hazelcast cache

IMap<String, MarketData> cache = hazelcast.getMap("market-snapshot");

MarketData data = cache.get(symbol);

if (data != null) {

ws.writeTextMessage(data.toJson());

}

}

private void handleLongPolling(HttpServerRequest req, String symbol) {

String lastEventId = req.getParam("lastEventId");

// Hold request until data available or timeout

long timerId = vertx.setTimer(30000, id -> {

req.response()

.putHeader("Content-Type", "application/json")

.end("{\"type\":\"heartbeat\"}");

});

// Register one-time listener

subscriptions.computeIfAbsent(symbol + ":poll",

k -> ConcurrentHashMap.newKeySet())

.add(new PollHandler(req, timerId));

}

private void broadcastToSubscribers(MarketData data) {

String symbol = data.getSymbol();

// WebSocket subscribers

Set<ServerWebSocket> sockets = subscriptions.get(symbol);

if (sockets != null) {

String json = data.toJson();

sockets.forEach(ws -> {

if (!ws.isClosed()) {

ws.writeTextMessage(json);

}

});

}

// Update Hazelcast cache for new subscribers

IMap<String, MarketData> cache = hazelcast.getMap("market-snapshot");

cache.put(symbol, data);

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

new MarketDataServer().start();

}

}

Publishing market data to Hazelcast from data feed:

public class MarketDataPublisher {

private final HazelcastInstance hazelcast;

public void publishUpdate(String symbol, double price, long volume) {

MarketData data = new MarketData(symbol, price, volume,

System.currentTimeMillis());

// Publish to topic - all Vert.x instances receive it

ITopic<MarketData> topic = hazelcast.getTopic("market-data");

topic.publish(data);

}

}

This architecture provided:

- Vert.x Event Loop: Non-blocking I/O handled 10,000+ concurrent WebSocket connections per instance

- Hazelcast Distribution: Market data shared across multiple Vert.x instances without a central message broker

- Horizontal Scaling: Adding Vert.x instances automatically joined the Hazelcast cluster

- Low Latency: Sub-millisecond message propagation within the cluster

- Automatic Fallback: Clients detected WebSocket support; older browsers used long polling

Facebook Thrift and Google Protocol Buffers

I experimented with Facebook Thrift and Google Protocol Buffers that provided IDL-based RPC with multiple protocols: Here is an example of Protocol Buffers:

syntax = "proto3";

package customer;

message Customer {

int32 customer_id = 1;

string name = 2;

double balance = 3;

}

service CustomerService {

rpc GetCustomer(GetCustomerRequest) returns (Customer);

rpc UpdateBalance(UpdateBalanceRequest) returns (UpdateBalanceResponse);

rpc ListCustomers(ListCustomersRequest) returns (CustomerList);

}

message GetCustomerRequest {

int32 customer_id = 1;

}

message UpdateBalanceRequest {

int32 customer_id = 1;

double new_balance = 2;

}

message UpdateBalanceResponse {

bool success = 1;

}

message ListCustomersRequest {}

message CustomerList {

repeated Customer customers = 1;

}

Python server with gRPC (which uses Protocol Buffers):

import grpc

from concurrent import futures

import customer_pb2

import customer_pb2_grpc

class CustomerServicer(customer_pb2_grpc.CustomerServiceServicer):

def GetCustomer(self, request, context):

return customer_pb2.Customer(

customer_id=request.customer_id,

name="John Doe",

balance=5000.00

)

def UpdateBalance(self, request, context):

print(f"Updating balance for {request.customer_id} " +

f"to {request.new_balance}")

return customer_pb2.UpdateBalanceResponse(success=True)

def ListCustomers(self, request, context):

customers = [

customer_pb2.Customer(customer_id=1, name="Alice", balance=1000),

customer_pb2.Customer(customer_id=2, name="Bob", balance=2000),

]

return customer_pb2.CustomerList(customers=customers)

def serve():

server = grpc.server(futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=10))

customer_pb2_grpc.add_CustomerServiceServicer_to_server(

CustomerServicer(), server)

server.add_insecure_port('[::]:50051')

server.start()

print("Server started on port 50051")

server.wait_for_termination()

if __name__ == '__main__':

serve()

I learned that binary protocols offer significant efficiency gains. JSON is human-readable and convenient for debugging, but in high-performance scenarios, binary protocols like Protocol Buffers reduce payload size and serialization overhead.

Serverless and Lambda: Functions as a Service

Around 2015, AWS Lambda introduced serverless computing where you wrote functions, and AWS handled all the infrastructure:

// Lambda function (Node.js)

exports.handler = async (event) => {

const customerId = event.queryStringParameters.customerId;

// Query DynamoDB

const AWS = require('aws-sdk');

const dynamodb = new AWS.DynamoDB.DocumentClient();

const result = await dynamodb.get({

TableName: 'Customers',

Key: { customerId: customerId }

}).promise();

if (result.Item) {

return {

statusCode: 200,

body: JSON.stringify(result.Item)

};

} else {

return {

statusCode: 404,

body: JSON.stringify({ error: 'Customer not found' })

};

}

};

Serverless was powerful with no servers to manage, automatic scaling, pay-per-invocation pricing. It felt like the Actor model I’d worked for my research that offered small, stateless, event-driven functions.

However, I also encountered several problems with serverless:

- Cold starts: First invocation could be slow (though it has improved with recent updates)

- Timeouts: Functions had maximum execution time (15 minutes for Lambda)

- State management: Functions were stateless; you needed external state stores

- Orchestration: Coordinating multiple functions was complex

The ping-pong anti-pattern emerged where Lambda A calls Lambda B, which calls Lambda C, which calls Lambda D. This created hard-to-debug systems with unpredictable costs. AWS Step Functions and Azure Durable Functions addressed orchestration:

{

"Comment": "Order processing workflow",

"StartAt": "ValidateOrder",

"States": {

"ValidateOrder": {

"Type": "Task",

"Resource": "arn:aws:lambda:us-east-1:123456789012:function:ValidateOrder",

"Next": "CheckInventory"

},

"CheckInventory": {

"Type": "Task",

"Resource": "arn:aws:lambda:us-east-1:123456789012:function:CheckInventory",

"Next": "ChargeCustomer"

},

"ChargeCustomer": {

"Type": "Task",

"Resource": "arn:aws:lambda:us-east-1:123456789012:function:ChargeCustomer",

"Catch": [{

"ErrorEquals": ["PaymentError"],

"Next": "PaymentFailed"

}],

"Next": "ShipOrder"

},

"ShipOrder": {

"Type": "Task",

"Resource": "arn:aws:lambda:us-east-1:123456789012:function:ShipOrder",

"End": true

},

"PaymentFailed": {

"Type": "Fail",

"Cause": "Payment processing failed"

}

}

}

gRPC: Modern RPC

In early 2020s, I started using gRPC extensively. It combined the best ideas from decades of RPC evolution:

- Protocol Buffers for IDL

- HTTP/2 for transport (multiplexing, header compression, flow control)

- Strong typing with code generation

- Streaming support (unary, server streaming, client streaming, bidirectional)

Here’s a gRPC service definition:

syntax = "proto3";

package customer;

service CustomerService {

rpc GetCustomer(GetCustomerRequest) returns (Customer);

rpc UpdateCustomer(Customer) returns (UpdateResponse);

rpc StreamOrders(StreamOrdersRequest) returns (stream Order);

rpc BidirectionalChat(stream ChatMessage) returns (stream ChatMessage);

}

message Customer {

int32 customer_id = 1;

string name = 2;

double balance = 3;

}

message GetCustomerRequest {

int32 customer_id = 1;

}

message UpdateResponse {

bool success = 1;

string message = 2;

}

message StreamOrdersRequest {

int32 customer_id = 1;

}

message Order {

int32 order_id = 1;

double amount = 2;

string status = 3;

}

message ChatMessage {

string user = 1;

string message = 2;

int64 timestamp = 3;

}

Go server implementation:

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"log"

"net"

"time"

"google.golang.org/grpc"

pb "example.com/customer"

)

type server struct {

pb.UnimplementedCustomerServiceServer

}

func (s *server) GetCustomer(ctx context.Context, req *pb.GetCustomerRequest) (*pb.Customer, error) {

return &pb.Customer{

CustomerId: req.CustomerId,

Name: "John Doe",

Balance: 5000.00,

}, nil

}

func (s *server) UpdateCustomer(ctx context.Context, customer *pb.Customer) (*pb.UpdateResponse, error) {

log.Printf("Updating customer %d", customer.CustomerId)

return &pb.UpdateResponse{

Success: true,

Message: "Customer updated successfully",

}, nil

}

func (s *server) StreamOrders(req *pb.StreamOrdersRequest, stream pb.CustomerService_StreamOrdersServer) error {

orders := []*pb.Order{

{OrderId: 1, Amount: 99.99, Status: "shipped"},

{OrderId: 2, Amount: 149.50, Status: "processing"},

{OrderId: 3, Amount: 75.25, Status: "delivered"},

}

for _, order := range orders {

if err := stream.Send(order); err != nil {

return err

}

time.Sleep(time.Second) // Simulate delay

}

return nil

}

func (s *server) BidirectionalChat(stream pb.CustomerService_BidirectionalChatServer) error {

for {

msg, err := stream.Recv()

if err != nil {

return err

}

log.Printf("Received: %s from %s", msg.Message, msg.User)

// Echo back with server prefix

response := &pb.ChatMessage{

User: "Server",

Message: fmt.Sprintf("Echo: %s", msg.Message),

Timestamp: time.Now().Unix(),

}

if err := stream.Send(response); err != nil {

return err

}

}

}

func main() {

lis, err := net.Listen("tcp", ":50051")

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to listen: %v", err)

}

s := grpc.NewServer()

pb.RegisterCustomerServiceServer(s, &server{})

log.Println("Server listening on :50051")

if err := s.Serve(lis); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to serve: %v", err)

}

}

Go client:

package main

import (

"context"

"io"

"log"

"time"

"google.golang.org/grpc"

"google.golang.org/grpc/credentials/insecure"

pb "example.com/customer"

)

func main() {

conn, err := grpc.Dial("localhost:50051",

grpc.WithTransportCredentials(insecure.NewCredentials()))

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to connect: %v", err)

}

defer conn.Close()

client := pb.NewCustomerServiceClient(conn)

ctx := context.Background()

// Unary call

customer, err := client.GetCustomer(ctx, &pb.GetCustomerRequest{

CustomerId: 12345,

})

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("GetCustomer failed: %v", err)

}

log.Printf("Customer: %v", customer)

// Server streaming

stream, err := client.StreamOrders(ctx, &pb.StreamOrdersRequest{

CustomerId: 12345,

})

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("StreamOrders failed: %v", err)

}

for {

order, err := stream.Recv()

if err == io.EOF {

break

}

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Receive error: %v", err)

}

log.Printf("Order: %v", order)

}

}

The Load Balancing Challenge

gRPC had one major gotcha in Kubernetes: connection persistence breaks load balancing. I documented this exhaustively in my blog post The Complete Guide to gRPC Load Balancing in Kubernetes and Istio. HTTP/2 multiplexes multiple requests over a single TCP connection. Once that connection is established to one pod, all requests go there. Kubernetes Service load balancing happens at L4 (TCP), so it doesn’t see individual gRPC calls and it only sees one connection. I used Istio’s Envoy sidecar, which operates at L7 and routes each gRPC call independently:

apiVersion: networking.istio.io/v1beta1

kind: DestinationRule

metadata:

name: grpc-service

spec:

host: grpc-service

trafficPolicy:

connectionPool:

http:

http2MaxRequests: 100

maxRequestsPerConnection: 10 # Force connection rotation

loadBalancer:

simple: LEAST_REQUEST # Better than ROUND_ROBIN

outlierDetection:

consecutiveErrors: 5

interval: 30s

baseEjectionTime: 30s

I learned that modern protocols solve old problems but introduce new ones. gRPC is excellent, but you must understand how it interacts with infrastructure. Production systems require deep integration between application protocol and deployment environment.

Modern Messaging and Streaming

I have been using Apache Kafka for many years that transformed how we think about data. It’s not just a message queue instead it’s a distributed commit log:

from kafka import KafkaProducer, KafkaConsumer

import json

# Producer

producer = KafkaProducer(

bootstrap_servers='localhost:9092',

value_serializer=lambda v: json.dumps(v).encode('utf-8')

)

order = {

'order_id': '12345',

'customer_id': '67890',

'amount': 99.99,

'timestamp': time.time()

}

producer.send('orders', value=order)

producer.flush()

# Consumer

consumer = KafkaConsumer(

'orders',

bootstrap_servers='localhost:9092',

auto_offset_reset='earliest',

value_deserializer=lambda m: json.loads(m.decode('utf-8')),

group_id='order-processors'

)

for message in consumer:

order = message.value

print(f"Processing order: {order['order_id']}")

# Process order

Kafka’s provided:

- Durability: Messages are persisted to disk

- Replayability: Consumers can reprocess historical events

- Partitioning: Horizontal scalability through partitions

- Consumer groups: Multiple consumers can process in parallel

Key Lesson: Event-driven architectures enable loose coupling and temporal decoupling. Systems can be rebuilt from the event log. This is Event Sourcing—a powerful pattern that Kafka makes practical at scale.

Agentic RPC: MCP and Agent-to-Agent Protocol

Over the last year, I have been building Agentic AI applications using Model Context Protocol (MCP) and more recently Agent-to-Agent (A2A) protocol. Both use JSON-RPC 2.0 underneath. After decades of RPC evolution, from Sun RPC to CORBA to gRPC, we’ve come full circle to JSON-RPC for AI agents. I recently built a daily minutes assistant that aggregates information from multiple sources into a morning briefing. After decades of RPC evolution, from Sun RPC to CORBA to gRPC, it has come full circle to JSON-RPC for AI agents.

Service Discovery

A2A immediately reminded me of Sun’s Network Information Service (NIS), originally called Yellow Pages that I used in early 1990s. NIS provided a centralized directory service for Unix systems to look up user accounts, host names, and configuration data across a network. I saw this pattern repeated throughout the decades:

- CORBA Naming Service (1990s): Objects registered themselves with a hierarchical naming service, and clients discovered them by name

- JINI (late 1990s): Services advertised themselves via multicast, and clients discovered them through lookup registrars (as I described earlier in the JINI section)

- UDDI (2000s): Universal Description, Discovery, and Integration for web services—a registry where SOAP services could be published and discovered

- Consul, Eureka, etcd (2010s): Modern service discovery for microservices

- Kubernetes DNS/Service Discovery (2010s-present): Built-in service registry and DNS-based discovery

Model Context Protocol (MCP)

MCP lets AI agents discover and invoke tools provided by servers. I recently built a daily minutes assistant that aggregates information from multiple sources into a morning briefing. Here’s the MCP server that exposes tools to the AI agent:

from mcp.server import Server

import mcp.types as types

from typing import Any

import asyncio

class DailyMinutesServer:

def __init__(self):

self.server = Server("daily-minutes")

self.setup_handlers()

def setup_handlers(self):

@self.server.list_tools()

async def handle_list_tools() -> list[types.Tool]:

return [

types.Tool(

name="get_emails",

description="Fetch recent emails from inbox",

inputSchema={

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"hours": {

"type": "number",

"description": "Hours to look back"

},

"limit": {

"type": "number",

"description": "Max emails to fetch"

}

}

}

),

types.Tool(

name="get_hackernews",

description="Fetch top Hacker News stories",

inputSchema={

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"limit": {

"type": "number",

"description": "Number of stories"

}

}

}

),

types.Tool(

name="get_rss_feeds",

description="Fetch latest RSS feed items",

inputSchema={

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"feed_urls": {

"type": "array",

"items": {"type": "string"}

}

}

}

),

types.Tool(

name="get_weather",

description="Get current weather forecast",

inputSchema={

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"location": {"type": "string"}

}

}

)

]

@self.server.call_tool()

async def handle_call_tool(

name: str,

arguments: dict[str, Any]

) -> list[types.TextContent]:

if name == "get_emails":

result = await email_connector.fetch_recent(

hours=arguments.get("hours", 24),

limit=arguments.get("limit", 10)

)

elif name == "get_hackernews":

result = await hn_connector.fetch_top_stories(

limit=arguments.get("limit", 10)

)

elif name == "get_rss_feeds":